I’d got some managers, the first I’d ever had in my life. They were like, ‘Did you ever write a book?’ I said, ‘Well, I actually gave it a shot 10, 15 years ago, and it just didn’t feel right.’ At the time I couldn’t figure the whole thing out. I had no way of ending even that particular chapter of my life. But then I suddenly had my most productive three years yet in 2017, 2018 and 2019. It took me completely by surprise: it was bizarre. This cat called Leo Green casually asked when we were coming back to London, and I said, ‘We come back every November for my wife Maureen’s birthday, but this year we’re coming early for Bill Wyman’s 80th birthday party.’ ‘That’s the same week as my blues festival,’ he said. ‘Put a band together and headline one of the nights.’ ‘Well, Leo,’ I said, ‘it’s a fun thought but I haven’t done the Disciples of Soul in a mere 30 fucking years.’ But the idea grew on me. I could bring back the horns, do some Paul Butterfield and Electric Flag stuff, and throw in a couple of my own songs which I hadn’t even thought about for years.

The old songs were a bit of a revelation. I was like, ‘Man, this is more interesting than I remember!’ It was never fashionable, this rock-meets-soul thing, so it’s timeless in a way. One thing led to another. The band was so good, someone said ‘Let’s do an album.’ ‘I haven’t written an album for myself in 30 years, so let’s do an album of songs by other people,’ I said. That became the Soulfire album. Then some guy said, ‘I love for you to do a tour.’ On the tour, new ideas started to come to me, and they became The Summer of Sorcery. We toured nonstop for three years: Europe four times, America three times, Australia, New Zealand. It was a wonderful time. I reconnected with my life’s work, which I’d kind of abandoned without realizing it.

The day after I filmed The Irishman with Marty Scorsese, we started a tour at the Roundhouse in London. I heard Paul McCartney was coming to the show, so in the last five minutes of the soundcheck I worked up Little Richard’s version of ‘I Saw Her Standing There’. Paul was the one who turned me onto Little Richard, along with most of America. When he came in I said, ‘Listen, man, you’ve been clearly working hard lately, just touring nonstop. You never go out, you never socialize. You and Nancy sit with Maureen and just enjoy the show.’

We’re taking the encore bow, and someone runs up on stage and says, ‘Paul’s coming up.’ I wasn’t expecting him. I was like, ‘Oh my goodness, I hope we remember what we rehearsed.’ Paul on stage with the E Street Band in Hyde Park in London was thrilling and fun, and then he invited me onstage with him at Madison Square Garden in New York; that was fun too. But him coming on my stage with my music and my band? The thrill of a lifetime. That tour started with Beatle consciousness, and then we were going to Liverpool. I said, ‘The Beatles used to do lunchtime sets for the local office workers.’ So we called the Cavern, and they said they hadn’t done that for 40 years, but let’s give it a shot. We did a lunchtime set, half Beatles songs with horns, which people rarely hear live, and half covers that they did at the Cavern: Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Larry Williamson. We rehearsed it on the bus, and that became the Macca to Mecca album.

In three years we did two studio albums, two live albums, my entire Lilyhammer score and remastered my entire catalog as Rock ’n’ Roll Rebel. It really did seem like closure and I felt like I could write the book: I had an ending that would work. But the writing wasn’t easy. I have a whole new respect for authors. What do you leave out, what do you leave in? I wanted to write every word. I didn’t want a ghostwriter. I figured out early on that part of the trick is making sure it’s in your own voice. So I pictured doing the audio book and wrote it like I talk. I told the publisher, ‘This is not going to be grammatically correct, but the way I’ll write it will sound like me.’

It’s a tough time to try and plan anything. Everybody’s having the same problem. I’m giving Bruce Springsteen first priority. If he wants to go out in 2022, I’ll do that, and that’ll be two years — boom, gone. Anything I might be planning creatively — assuming he goes out, which is not an absolute — is going to be for 2024, 2025: keeping the Disciples of Soul together, going back to TV. I’ve got five scripts written and 25 treatments. One of the reasons I wanted to write Unrequited Infatuations was that I was hoping it would explain my life to me. You go back to some painful mistakes, and it’s no fun to relive them, but I wanted to be totally honest. And if you really get into it, you start to see the logic of what you did, even if it was a mistake. It helps in a way. It’s a bit cathartic. If you had to do it all over again, of course you could have done things differently. But would you have? You have to be honest: you wouldn’t. I probably would have done the same fucking thing all over again, you know?

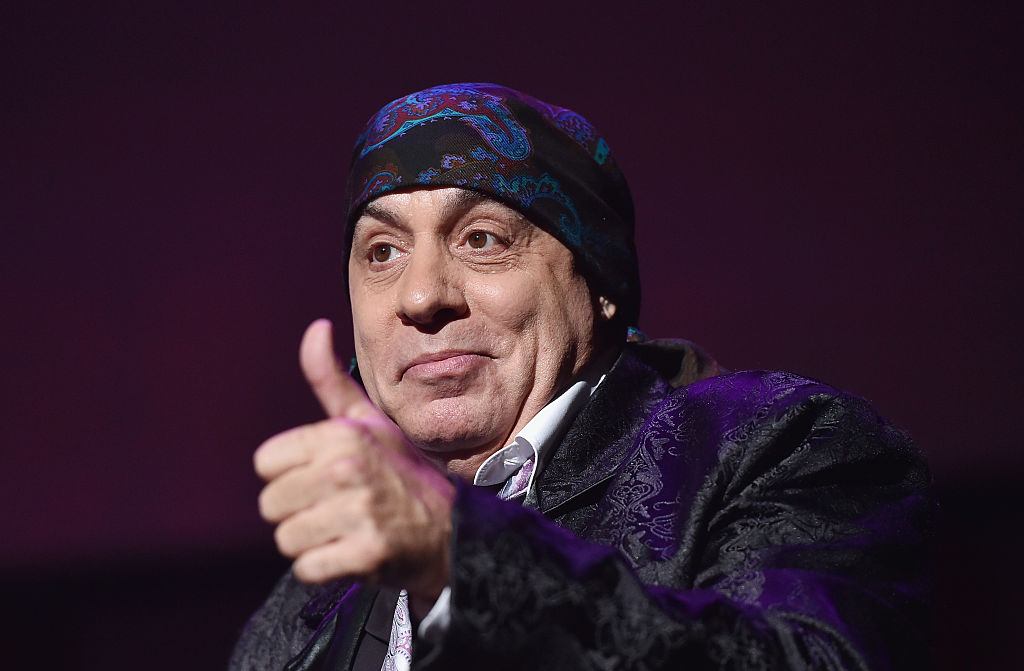

Steven van Zandt’s autobiography, Unrequited Infatuations: A Memoir, is published by Hachette ($31). This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2021 World edition.