It’s always easier to break something than to build it.

Joe Biden broke the immigration control system that he’d inherited from Donald Trump and that had been built up over several administrations of both parties. Rebuilding it after Biden’s vandalism will take time. Even if Republicans win the majority in both houses of Congress in November, it will take a change in administration before any real reconstruction can begin.

With more than 2 million “encounters” with illegal border-crossers over the past year, more than any year in history, restoring order may seem like an insuperable task. But as we saw right after Trump’s election and during the first months of his presidency, a simple expression of will can have a huge influence on prospective illegal aliens and their smugglers.

But rhetoric won’t be enough. Thankfully, Republicans seem to get that. The House GOP leadership recently presented an immigration security outline that includes many of the needed changes.

Regaining control must mean, first of all, a return to a policy of deterring illegal immigration, not merely processing those who make it across the border, which is the Biden administration’s policy.

The key to successful deterrence is ending the practice of catch-and-release. Under this president, well over 1 million illegal aliens have been intentionally released into the country. (The rest of the illegal alien “encounters” were expelled back across the border under Title 42, a Covid-era public health measure that the Biden DHS is trying to end.) If border-jumpers are released, more will follow, as they pass the news to family and friends. If they’re detained, or made to wait outside the US, fewer will come, as they relay that news.

That’s why “Build the Wall!” is insufficient. There’s no question that more wall has to be constructed, especially in those areas where Biden’s Inauguration Day stop-work order has left gaps that are irresistible to alien smugglers. And restarting wall construction will, by itself, send the message that things have changed.

But the Border Patrol will also have to be built up again, since more agents are now leaving in disgust than are being replaced by new hires. Detention beds will need to be added, to comply with the statutory mandate that all illegal border-crossers be detained until the final deposition of their cases. (The decision to ignore that mandate early in Obama’s first term is what lit the fuse for the past decade’s border mess.) Immigration court facilities will need to be maintained at all the major ports of entry along the Mexican border.

The physical wall, and the infrastructure and personnel that accompany it, will need to be buttressed by a legal and policy “wall” to end catch-and-release. A veritable archipelago of loopholes in the immigration law have to be plugged, which will require our legislature to rouse itself and legislate.

Some of the more important loopholes:

- Illegal alien minors who cross the border without parent or guardian, and are from countries not on our borders, are given a partial exemption from enforcement. This has led to the perverse result of the federal government completing the smuggling process by delivering the minors to their (usually illegal alien) parents in the United States.

- An eccentric judicial interpretation of the Flores settlement, stemming from a long-ago lawsuit, virtually guarantees release into the US of any illegal alien accompanying a child.

- The standard used in the initial screening step in the asylum process, known as the “credible fear” interview, needs to be raised significantly; nearly everyone who isn’t receiving microwave messages through his dental work passes this hurdle, even though few go on to actually qualify for asylum.

- Congress has given the executive very narrow authority to release into the country aliens who have no right to enter, called “parole.” It was intended for the occasional medical emergency and the like, but it’s been used by the Biden administration on a mass scale. It needs to be restricted or abolished altogether.

- Asylum was originally intended to address the cases of a handful of Soviets and other defectors who didn’t have any basis for being admitted as immigrants. Yet it’s grown into a loophole that threatens to swallow immigration enforcement. Generalized crime and insecurity, gang recruitment, extortion attempts, domestic abuse, physical disability — all these have been used as grounds for asylum, giving ever-larger numbers of illegal aliens a trapdoor through the border. Some tightening was done administratively under Trump, but tightening up the statute would make it harder for a subsequent administration to reverse, as we’re seeing today.

In addition to plugging loopholes, new policies are needed. Asylum in particular needs to be rethought from scratch, since it’s a relic from another era. In the meantime, though, two major changes would limit the attractiveness of asylum claims to alien smugglers and prospective illegal aliens.

First, Remain in Mexico needs to be reinstated and expanded. This program, formally known as the Migrant Protection Protocols, was instituted during the Trump administration and required certain asylum-seekers to wait in Mexico until their hearing dates rather than be released into the US. It was extraordinarily effective in deterring bogus claims of asylum.

But Mexico accepted the return of only certain nationalities, so this concept should be expanded. Currently, the law that Remain in Mexico is based on provides for the return of illegal aliens only to the contiguous country they snuck in from — i.e., Mexico. But Britain and Denmark have developed plans under which illegal aliens who claim asylum are sent to Rwanda to have their claims adjudicated (Australia and Israel have had similar frameworks). If the US were to supplement Remain in Mexico with, say, Remain in Paraguay, or Remain in Djibouti, or Remain in Mongolia, asylum abuse would become that much harder.

The second needed asylum change seeks to nip the problem in the bud, barring people from applying for asylum at all if they’ve passed through other countries before reaching the US. This practice of country-shopping — traveling through many countries before reaching the one whose immigration system is easiest to game — is not even required by the UN treaty our asylum rules are based on.

The prior administration negotiated “Asylum Cooperative Agreements” with the Northern Triangle countries of Central America — El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras — that required third-country nationals to apply for asylum in one of those nations if they passed through them, rather than continue on to the Rio Grande, and sent them back to those places if they didn’t apply there. The Biden administration terminated those arrangements within days of taking over.

These are just some of the building blocks of a Republican border control policy. Border control doesn’t begin or end at the border, and so other steps would also be needed. Sanctuary cities need to be reined in; independent authority to assist in immigration enforcement must be returned to the states; deportations from inside the country must resume (they’ve fallen to almost nothing, even for criminals); and the magnet of jobs — which is what illegal aliens are coming for in the first place — needs to be turned off via universal use of the E-Verify system for new hires.

Putting the pieces of the broken border system back together again will take time, but it can be done.

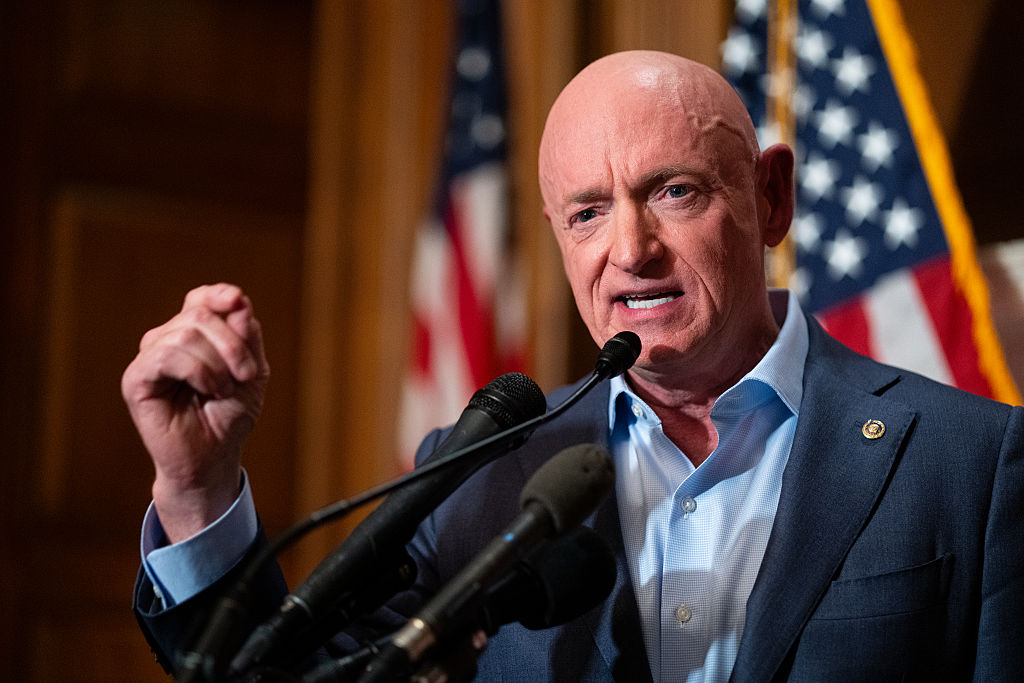

Mark Krikorian is the executive director of the Center for Immigration Studies