In May, when a federal jury acquitted former Hillary Clinton campaign lawyer Michael Sussmann of one count of lying to the FBI, the cadre of politicians, pundits and activists that comprise what they consider a “resistance” to Donald Trump’s presidency were brimming with indignation at the insult of its having gone to trial at all.

The Sussmann prosecution was the first case from special counsel John Durham to go to trial. Durham was appointed in 2019 to investigate the FBI’s investigation of the Trump campaign’s connections to Russia. And it took only a few hours for the jury to rule against him. As Harvard law professor Laurence Tribe told Politico: “The Durham roadshow has expended far too much of the taxpayers’ money with precious little to show for it and needs to be wound down in an orderly fashion. Enough already!”

Tribe’s view of Durham’s prosecution of Sussmann is ironic. Only a few years earlier, the very same resistance denounced anyone who attacked the integrity of Robert Mueller, the special counsel who examined the Trump campaign’s ties to Russia. And yet when Mueller’s team found no evidence of conspiracy, the resistance did not complain that the hunt to prove Trump’s collusion was wasteful.

Such criticism of Durham is also myopic. Most of the evidence his team disclosed in the trial was not contested. Prosecutors, for example, found text messages from Sussmann to the FBI’s former general counsel, James Baker, explicitly stating that he was acting only as a private citizen when he requested an urgent meeting to discuss a threat to national security. Yet the prosecutors also presented billing records for Sussmann’s meeting with Baker, charging the time to the Clinton campaign and a private cybersecurity firm. Baker testified at the trial that Sussmann had said he was acting as a good citizen and not as a lawyer representing Trump’s opponent.

The information Sussmann passed to the FBI was laid out in several white papers that detailed allegedly unusual communications between computer servers in the Trump organization and Russia’s largest private bank. Clinton’s campaign leaked this story to Slate and others — and then touted the scoop on Clinton’s Twitter feed. As lead prosecutor Brittain Shaw told the jury, Sussmann “went straight to the FBI general counsel’s office, the FBI’s top lawyer. He then sat across from that lawyer and lied to him. He told a lie that was designed to achieve a political end, a lie that was designed to inject the FBI into a presidential election.”

The problem with Durham’s prosecution of Sussmann is that the evidence presented to the jury would be better suited to a trial of the former leadership of the FBI. For example, after field agents looked at the white papers and dismissed them as shoddy research, a senior manager from FBI headquarters told them to keep the probe open as a counterintelligence investigation, noting that FBI leadership was keenly interested. What’s more, the opening of the server investigation did not mention that the tip came from a Clinton campaign lawyer; instead it said it came from the Justice Department. When the bureau’s investigators wanted to know the identity of the person who had brought the white papers to the FBI, they were told the source would have to remain confidential.

None of these details mattered, though, to the outcome of the trial itself. The FBI was not on trial; Sussmann was. And Sussmann was not charged with defrauding the US government or conspiring with FBI officials for a partisan dirty trick. He was charged with deceiving the FBI about who he was representing in a meeting. This made Sussmann’s defense fairly easy. His lawyers successfully proved that the FBI knew that Sussmann worked for Clinton’s campaign, so that the alleged lie was not material to the bureau’s investigation. After all, Sussmann represented the campaign to the FBI after it was hacked by Russian operatives in the summer of 2016. He even helped edit the bureau’s press release about it. Sussmann may have told Baker he was not representing a client when he passed on the white papers, but everyone on the FBI’s leadership team knew who he was.

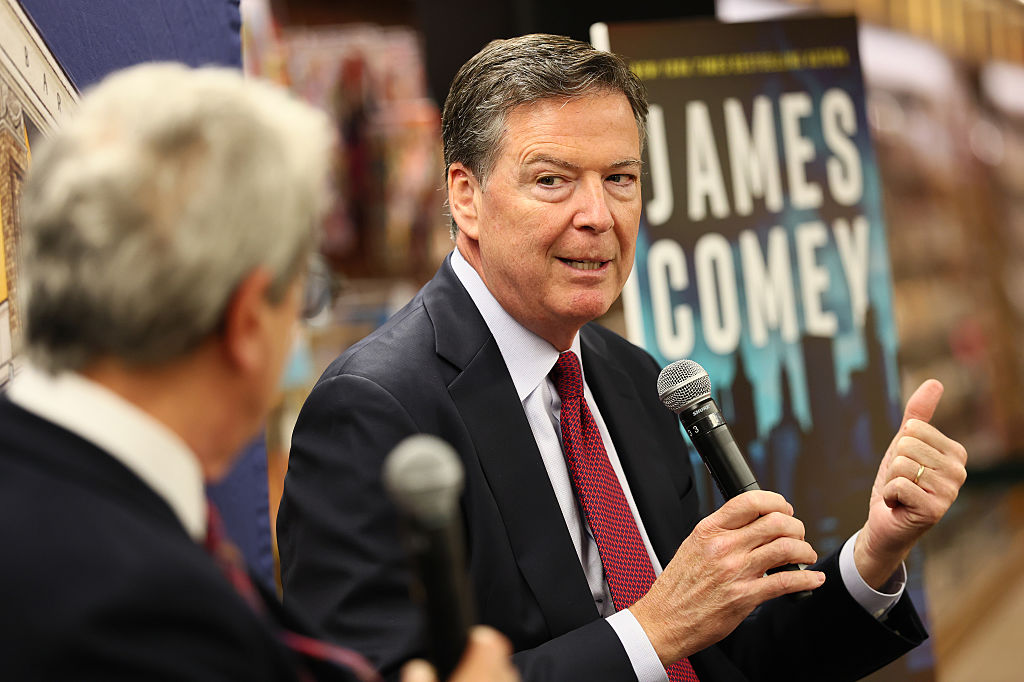

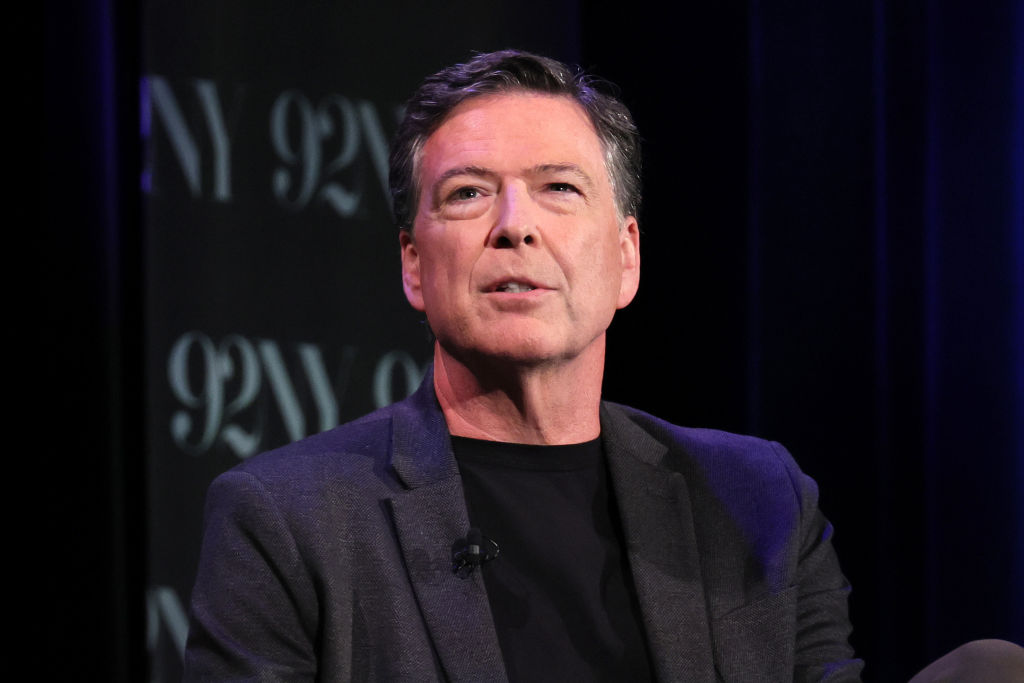

The details that emerged from the Sussmann trial are important because they put the lie to a myth about the 2016 election. Since Clinton lost that year, the Democratic Party has largely accepted a narrative that blames her defeat on Russian hackers and former FBI director James Comey, who announced in the middle of the campaign that Clinton would not be prosecuted for operating a private email server for official business when she was secretary of state. But just two weeks before Americans voted, Comey announced he was reopening the server investigation after new Clinton emails were discovered on the computer of disgraced former representative Anthony Weiner, who was married to Clinton’s chief of staff. Only two days before the election, the FBI announced (again) that it was re-closing the probe.

Comey’s last-minute intervention cast a cloud over Clinton’s campaign. What Durham’s investigation has shown is that Clinton’s allies and lawyers fed the FBI a stream of rumor and innuendo suggesting Trump and his aides were in bed with the Russians in hopes of casting a similar cloud over his campaign. That effort failed. But after Trump won, the FBI’s leadership was eager to use the Clinton campaign’s research to bolster their own failing probe into her opponent.

This will be what to watch for in October, when the second trial to stem from Durham’s investigation will commence. Sitting in the dock this time will be Igor Danchenko, a Russian national who collected most of the so-called intelligence contained in the famous “Steele dossier” about Donald Trump’s campaign and its alleged interactions with Russia. This research was paid for by the Clinton campaign through a series of cut-outs: The campaign’s law firm, Perkins Coie, contracted an opposition research firm, Fusion GPS, which in turn paid a former MI6 operative, Christopher Steele, who then paid Danchenko to learn what he could about Trump and Russia.

During the presidential transition between Obama and Trump, Danchenko’s “research” was treated like Watergate revelations by the media and the Democratic Party. It alleged that Trump’s second campaign manager, Paul Manafort, had managed the campaign’s outreach to Russia as part of a well-developed conspiracy. It said Russian intelligence had tapes of Trump in Moscow, with prostitutes urinating on a bed where the Obamas had supposedly slept. Back in 2017, when BuzzFeed first published the dossier (following accurate leaks that it had been personally briefed to both Trump and Obama by Comey) the public did not know Danchenko had anything to do with it. The dossier was assumed to be credible because Steele was credible. It would take another three years to learn that Steele had relied on Danchenko.

And Danchenko was not reliable. Last year, he was charged with five counts of lying to the FBI during 2017 debriefings about his sourcing for the dossier. The theory of the case is that this former Brookings Institution researcher, himself once the subject of an FBI counterintelligence investigation as a possible Russian agent, hoodwinked the most powerful law enforcement agency in the world. Had Danchenko told the truth when first questioned, the FBI would have saved the time and resources it wasted on trying to confirm his tall tales.

The upcoming trial will also be revealing about other Democratic operatives who fed information into the dossier. Danchenko was not honest, according to Durham’s indictment, about his relationship with Charles Dolan Jr., a public relations executive who has been a close ally of the Clintons since the 1990s, serving as an advisor on Clinton’s 2008 campaign and a volunteer in 2016. Dolan was a source for some of the claims in the Steele dossier, according to the indictment, but when pressed by the FBI, Danchenko said he barely knew him and had never told Dolan about his Trump-related research.

Durham contends that both these claims were lies. It’s even more suspicious that in this period Dolan was operating as an unregistered foreign agent for the Russian Federation. Mueller’s prosecutors charged several Trump-world figures with violations of the rarely enforced Foreign Agents Registration Act. And yet Dolan was never charged.

If the only damage done by the Steele dossier had been to inject disinformation into American political discourse, there would only be a medium-level scandal. But Comey and the FBI took the dossier seriously, despite never verifying it. Comey himself, according to the Senate Intelligence Committee, personally lobbied — over the objections of CIA analysts — to include allegations from the dossier in a US intelligence assessment of Russia’s influence over the 2016 election. And when Comey briefed congressional leaders and the Justice Department in March 2017, we know from recently declassified FBI talking points, it was claimed that some of the dossier had already been corroborated and that it derived from a Russia-based source, when in fact Danchenko was a US resident at the time. By that point, the FBI had already conducted one interview with Danchenko — and he had begun to walk back some of the dossier’s claims. In other words, Comey presented the Steele dossier as credible information to Congress, just as lower-level agents were learning it was not to be trusted.

Savor the irony. Clinton has claimed that Comey’s October email surprise cast a cloud over her campaign that cost her the election. Meanwhile, Clinton’s agents fed the bureau enough thinly sourced dirt on Trump and Russia to cast doubts over his whole presidency. Comey only let the fog linger over Clinton until November 6, when he announced that a review of Weiner’s laptop revealed nothing incriminating. The miasma over Trump’s presidency lingered for two and a half years, until Mueller announced he had found no evidence of conspiracy between Russia and the Trump campaign. To this day, most Democrats still don’t believe that and ignore how that conspiracy theory was first whispered by their party’s own lawyers and operatives.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2022 World edition.