Now would seem to be an excellent time for the Pulitzer Committee to withdraw the award it bestowed on Walter Duranty in 1932 for his reporting on events in the Soviet Union.

I know I am far from the first to call on the Pulitzer Committee to withdraw the award. I know as well that the Pulitzer Committee responded to one such call in 2003 by declaring that it could find no “clear and convincing evidence of deliberate deception” in Duranty’s 1931 reports from the Soviet Union published in the New York Times in 1931. Those thirteen reports on which the original award was based, admits the Pulitzer statement, amount to work that “measured by today’s standards for foreign reporting, falls seriously short.” And time has moved on, etc., etc.

Given the new ethic of tearing down statues, removing portraits, renaming buildings and discarding books that don’t measure up to “today’s standards,” you would think the Pulitzer Committee would be more than eager at this point to revisit the Duranty matter.

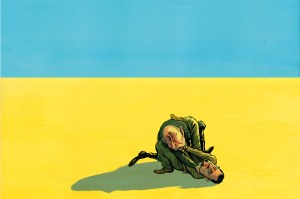

Duranty’s reports from the 1930s hid from American and Western readers Stalin’s engineered famine in Ukraine, where many million peasants were systemically starved to death. (How many million remains a matter of debate. Official death records, which surely were an undercount, yield a 3.3 million estimate; more speculative claims reach the seven to ten million mark.) The greatest number of those who succumbed to starvation died in 1932 and 1933. So the Pulitzer Committee has the excuse that it focused on Duranty’s 1931 reports, when the Ukrainian peasants were merely being brutalized, shot, exiled and having their property expropriated in preparation for government-ordered extermination.

Duranty has long since been convicted in the court of history as a moral monster, more interested in currying favor with the Soviet dictator than in conveying the truth about Stalin’s policies. The issue has never gone away in part because the New York Times continues to boast of Duranty’s Pulitzer as one of the heaps of honors it has accrued over the years. The Pulitzer Committee lends itself to this vainglory in its stubborn refusal to stand behind its decision of ninety years ago.

So why withdraw it now? Because we are at another historical juncture that reminds all the civilized world of the earlier atrocities — and the role of the press.

Duranty was a celebrated figure in the 1930s, known for having predicted the rise of Stalin — a rise that he helped along in some ways. In 1934, Viking Press released Duranty Reports Russia, the dust jacket of which helpfully explains, “A twelve-year record of a supreme feat of modern reporting — Walter Duranty’s day-to-day articles from Russia to the New York Times, selected and arranged to form a unique historical study.” But Duranty was in fact a fabulist. He accurately titled his 1936 memoir, I Write As I Please. That book received the same kind of adulation that his essays in support of Stalin had wrung from a credulous Western press. The reviewer Leland Stow described Duranty as “the dean of Anglo-Saxon typewriter-ambassadors to Moscow” whose “swift-flowing, graphic and penetrating account” of fourteen years in the Soviet Union is “a masterly narrative and an exceptionally honest human document.”

When W.H. Auden described the 1930s as “a low dishonest decade,” he might have had both the writer and the reviewer in mind. Duranty’s “exceptionally honest human document” is no less than a sustained attempt to cover up genocide.

The facts about both the famine and Duranty’s complicity in it have been in circulation for a long time. Perhaps the most notable account was S.J. Taylor’s 1990 book, Stalin’s Apologist: Walter Duranty, the New York Times’s Man in Moscow. But Duranty gained another kind of inspection in the 2019 movie, Mr. Jones, about the Welsh journalist Gareth Jones who was able to sneak into Ukraine in 1932 and escape with the true story. Nigel Jones’s piece in the UK Spectator, “Why Ukrainians Fear the Russians,” quotes some of Gareth Jones’s original reporting.

Ukrainians refer to Stalin’s mass starvation as the Holodomor (hunger plague). It was the culmination of Stalin’s efforts to impose collectivization on agriculture in the Soviet Union. It began in 1929 when the peasants were forced to relinquish their land and livestock to the state, and the peasants themselves were assigned the task of working on the new collective farms. Ukrainians resisted, especially as the Soviet government in its first “five-year plan” increased crop quotas and imposed new crops. By 1930, the Soviets began to expropriate crops. The peasants had to relinquish more and more of what they grew to support Stalin’s planned grain exports. A few years of diminishing harvests (bad weather was a factor) left the people with very little to eat. Any show of protest or resistance was met with harsh measures, including transport to Siberia.

By early 1932, the famine was in full swing. Some visitors took photographs of the horrors and wrote about them in the Western press, but at the New York Times, Walter Duranty was still busy assuring Americans that all was well in the communist utopia, and the ghastly stories of adults and children starving to death were mere anti-Soviet propaganda.

The details of the famine have been recounted endless times, enough so that the usual atrocity fatigue sets in. The human mind can contemplate such stuff only so long before it protects itself by putting the horrors in a kind of well-guarded museum. We know these things happen (Cambodia, Rwanda, Auschwitz), but to stare too long at them invites a kind of madness. “Look not too long in the face of fire, O man” warns Melville in Moby-Dick when Ishmael, standing night watch at the helm, is mesmerized by the glowing red of the kiln where whale blubber is being rendered. He nearly wrecks the ship before he recovers himself.

We are best off owning that men can commit deeds of measureless cruelty and do so on a scale that puts to shame our sense of pride in humanity. But then we should get back to the wholesome task of living. “Mortal man who hath more of joy than sorrow in him” (Melville again) has good work to do. And part of that work is setting right the lies and deceptions that have been handed down by our predecessors and taking care that we don’t perpetrate new ones.

The New York Times, unfortunately, has a hand in both. It is the self-proclaimed “newspaper of record” that adorns itself both with the skeleton of Walter Duranty and with the neo-racist mythology of the 1619 Project, also glorified with a Pulitzer Prize. The hollowness of that prize and the Times’s eagerness for the plastic honor is evident as well in the 2018 Pulitzer Prize Winner in National Reporting it received jointly with the Washington Post for their coverage of “Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election and its connections to the Trump campaign, the President-elect’s transition team and his eventual administration.”

Receiving a prize for coverage of something that never happened is the perfect mirror image of receiving a prize for not covering something that did. It is a nice embellishment that both awards deal with Russia. It is as though the Pulitzer Committee has a compulsion to align itself with falsehoods whenever there is a chance to build fake news on Russian perfidy.

But let’s focus on the incentives for making things right. The enthusiasm of the Pulitzer Committee for Nikole Hannah-Jones’s contributions to the 1619 Project presumably reflects the Committee’s eagerness to set the historical record right. After all, the entire purpose of the 1619 Project is to replace what Hannah-Jones deems a false narrative of America’s history with an accurate one, “for the first time.” The Pulitzer citation for the award says she is being honored for work “which seeks to place the enslavement of Africans at the center of America’s story, prompting public conversation about the nation’s founding and evolution.” In the effort to replace false narratives with truer ones, the Pulitzer Committee could take the brave step of abolishing its own long-standing false narrative about Walter Duranty’s contributions.

Putin’s war on Ukraine falls short of the scale of diabolical wickedness that Stalin achieved with mass murder by famine. I suppose Putin could catch up if he initiates a nuclear war, but at the moment we see only a blundering military operation aimed at wrecking a country. Still, it is enough to rekindle the memories of more than just the Ukrainians themselves that Russia has clawed its way through the corpse-strewn mud of this nation more than once before.

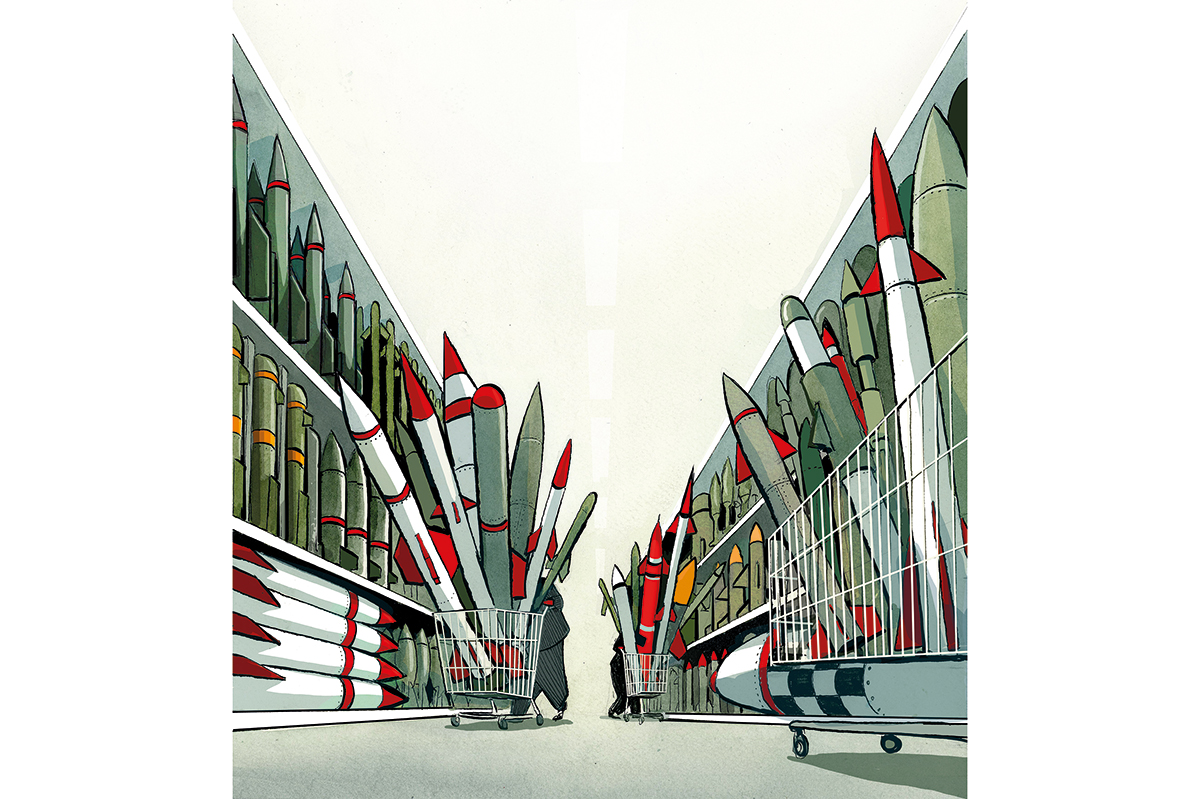

I am not among those urging the US to intervene militarily, and I see the recklessness of US policy in this region since the end of the Cold War. Mishandling Putin and undertaking covert operations in Ukrainian affairs over the last twenty years have played their parts in setting in motion this sorry tale of Biden’s incompetence and Putin’s belligerence.

We can’t fix that now. But maybe we can impose on ourselves a modest amount of historical reckoning. Americans in the 1930s shut their eyes and ears to Ukrainian suffering when it profited their own political agendas. Now, as Ukrainians suffer again, American institutions at the very least should relinquish the honors they gave and received as the publicity men for genocide. The Pulitzer Committee should at long last dispense with the pretense that its 1932 award to Walter Duranty was based on the merits of his work. A clever liar should be awarded a clever liar’s award, not a commendation for excellent journalism. Duranty was a clever liar and something worse, a perverter of truthful journalism to assist a murderous tyrant. Revoking Duranty’s award would show real remorse and real restitution — and show that American support for Ukraine is not just cheap virtue-signaling.

We might like to think this won’t happen again, but the unwillingness of a prideful committee to correct its past errors assures us of nothing but the prospect of further disgrace.