Vladimir Putin has been the most effective practitioner of Realpolitik for the past two decades. With an economy about the size of Italy’s, and just as corrupt, he has accomplished his most ambitious goal: returning Russia to the status of a Great Power. Now he’s thrown his chips on the table once more, launching a massive troop build-up on the border with Ukraine and sending still more into Belarus (for “joint exercises”), positioning them just north of Ukraine’s capital of Kyiv. Although the numbers don’t appear large enough to conquer all his neighbor’s territory, they are large enough to push through the eastern region (the one bordering Russia) and form a land bridge to Crimea, which Russia conquered in February 2014.

Western analysts are unsure whether Putin intends to launch another invasion or merely threaten one to gain concessions from Washington and NATO. His biggest demand — a non-starter — is an explicit NATO guarantee that it won’t expand its membership to include Ukraine, which Moscow considers a subordinate nation within its sphere of influence. Actually, Washington and its European allies have no intention of adding Ukraine to NATO, but they won’t publicly humiliate themselves by saying so. But Russia’s fear is not merely NATO troops on its doorstep. It also fears the example of a free and prosperous Ukraine across its border, looking far more attractive than Putin’s authoritarian regime. Putin’s troop deployment has already accomplished part of that goal by destabilizing Ukraine and discouraging foreign investment there.

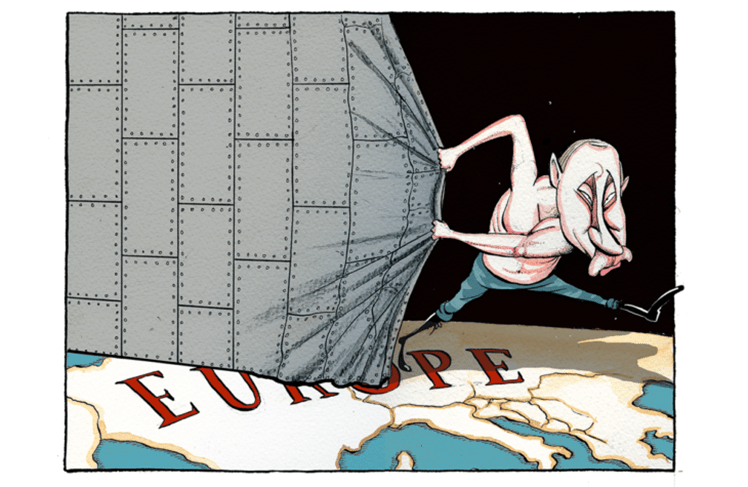

Given Putin’s expansive aims and his willingness to use military force (demonstrated in Crimea and the 2008 invasion of Georgia, the only times Europe’s borders have been changed by force since World War Two), how can he be stopped from invading Ukraine? Not by sweet talk, which is the German diplomatic approach in Moscow right now. In fact, Germany’s weak, commercially-driven foreign policy drives a wedge among NATO allies and gives Putin a partial victory at the very outset. After all, one of his primary goals has always been to divide the Western alliance and, if possible, break it.

Putin will only halt his prospective move on Ukraine if he fears the costs and risks of invasion are too high. That means effective deterrence, which relies on credible threats of severe punishment.

Deterrence will only work against Putin if four conditions apply simultaneously:

- The Biden administration is prepared to impose a heavy price on Moscow if it invades

- Biden makes that price crystal clear to Putin, both publicly and privately

- The Kremlin actually believes it will pay that heavy price; and finally

- Putin calculates that the prospective costs to his regime are not just higher than the prospective gains but high enough to endanger his control. He will invade only to strengthen his rule, not to jeopardize it

Let’s briefly consider each factor.

What kinds of costs could Washington and its NATO allies threaten? The most obvious are severe economic sanctions — not half-hearted ones on a few policymakers, like those Washington has previously imposed to no effect, but brutal ones to slash Moscow’s foreign-exchange earnings and sever its connections to the Western financial system.

Brutal sanctions means ending the Nord Stream II pipeline to Germany and cutting off Russian access to the interbank system, known as SWIFT. Some American hardliners have urged Nord Stream sanctions be imposed now. That would be a mistake, at this stage. True, it was probably a mistake to lift those sanctions earlier, as Biden did, but reimposing them now is less effective than holding them as a Sword of Damocles over Putin’s head, if he invades. The best way to convey that threat would be for Germany’s own leaders to say so publicly. So far, they have refused, raising the very danger they hope to avert and showing just how weak they really are.

Second, Biden needs to make his threats credible without forcing Putin to lose face by appearing to fold under American pressure. Accomplishing that would be difficult in any case, but it is far more difficult after Biden botched the Afghanistan withdrawal. Because America’s adversaries think Biden is weak, irresolute and incompetent, they don’t believe his threats. Perhaps they should; but they don’t. It doesn’t help that Biden was part of the Obama administration when Putin successfully changed Europe’s borders in Crimea.

Nor does it help when Biden garbles what should be a straightforward message of deterrence. That’s exactly what Biden did at his Wednesday press conference. Instead of holding up a big, bright-red stop sign, Biden seemed to wave a small white flag, seeming to give Putin permission for a “minor incursion.” He didn’t correct himself during the news conference so the White House was forced to send out its chief press spokesperson later to say Biden didn’t mean what had actually said. By then, unfortunately, the damage was done.

Biden’s problem now is that it is hard for him to make his deterrent threats credible. His failure could result in the worst of both worlds: he can’t dissuade Putin from using force, but he is saddled with the high costs and risks of actually imposing sanctions after Putin acts. The biggest risk is that Putin might respond with still further aggression, a still wider war.

The focus on Western economic sanctions has downplayed another crucial element of deterrence: the prospect of Russian soldiers coming home in body-bags to grieving families. No one expects the Ukrainian army to defeat the Russians outright, but they could make Moscow’s victory a Pyrrhic one. Imposing those costs requires a lot of weapons. So far, the Biden administration has been reluctant to supply them, though it hasn’t been as feckless as Obama administration, which gave the Ukrainians only blankets and meals. What that beleaguered country needs now is the equipment and training to destroy invading tanks, take down fighter jets, and kill soldiers coming across the border. Again, the idea is not to use any of them but to deter invasion through strength. The British have actually begun to transfer such weapons but the Germans — incredibly — refuse even to let British planes travel through their airspace. Once again, Putin is achieving his goal of dividing NATO allies.

Putin will act militarily against Ukraine unless he thinks the costs are too high. He won’t be restrained by international norms against aggressive war, any more than he was in Crimea or Georgia. He won’t care about grumbling in European foreign ministries. The only thing he cares about are the costs and risks of invasion, compared to the potential gains.

What would make the costs too high for him? Any risk to his regime. That could come in two ways. One would be the loss of support from the oligarchs he has made billionaires. They might bolt if they are cut off from all international finance and travel, but they would be risking their lives if they do. The other is the prospect of heavy casualties, the kind that helped bring down the Soviet Union after their costly failure in Afghanistan. That’s why Putin needs to fear serious losses among his invaders. The point would not be for Ukraine to win but for Putin’s victory to be too costly and, crucially, for Putin to know that in advance.

Convincing Putin he will pay those costs and that they will far outweigh any gains is a very hard task, indeed. It requires foresight, fortitude and forthright messaging from Washington. The Biden administration has bungled all three. The Germans have compounded the problem. That’s bad news if we hope to deter a very bad actor in the Kremlin.