As Russian forces level Ukrainian cities with artillery, missiles and airstrikes, there’s a concerted effort to get inside the mind of Vladimir Putin: from pundits, former US national security officials and current heads of government.

What could possibly get the man to stop the bombardment and support a ceasefire? Is Putin intent on conquering all of Ukraine? Or is there some combination of concessions the Ukrainian government and the West could offer that would end the war and bring about a full Russian troop withdrawal?

The fact is none of us know what Putin’s endgame is. Putin’s own advisors, especially those kept out of the inner circle, may not even understand what the Russian leader is planning.

Indeed, Putin himself may be vacillating between regime change in Kyiv, the demilitarization of Ukraine or splitting Ukraine into east and west and forcing the Ukrainian government into a deal on Russia’s terms. Some, however, are simply opting for the most extreme speculation available to explain the Russian strongman’s actions: Putin has lost his senses.

Former and current US officials from Condoleezza Rice and H.R. McMaster to Senator Marco Rubio have cast Putin as an irrational, isolated individual who is detached from reality, or at least strongly hinted that something may be wrong with Putin’s state of mind.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson of the UK didn’t even wait for Russia’s invasion to begin before telling the BBC he believed Putin was “thinking illogically” about Ukraine.

This isn’t the first time public officials have branded a foreign leader as deranged. In fact, US elites have a habit of throwing the word “crazy” around whenever bad people commit bad actions.

The examples are numerous. Ronald Reagan called Libya’s Muammar al-Gaddafi “the mad dog of the Middle East,” bent on inspiring an Islamic revolution.

A quarter-century later, when Gaddafi was ranting on television as his forces were squelching anti-government protesters with violence, Washington Post columnist David Ignatius wrote that “a reasonable person would conclude that the Libyan leader is a dangerous nut.”

During the run-up to the war in Iraq, author Anne Applebaum claimed that Saddam Hussein may not be deterrable because “megalomaniacal tyrants do not always behave in the way rational people do, and to assume otherwise is folly.”

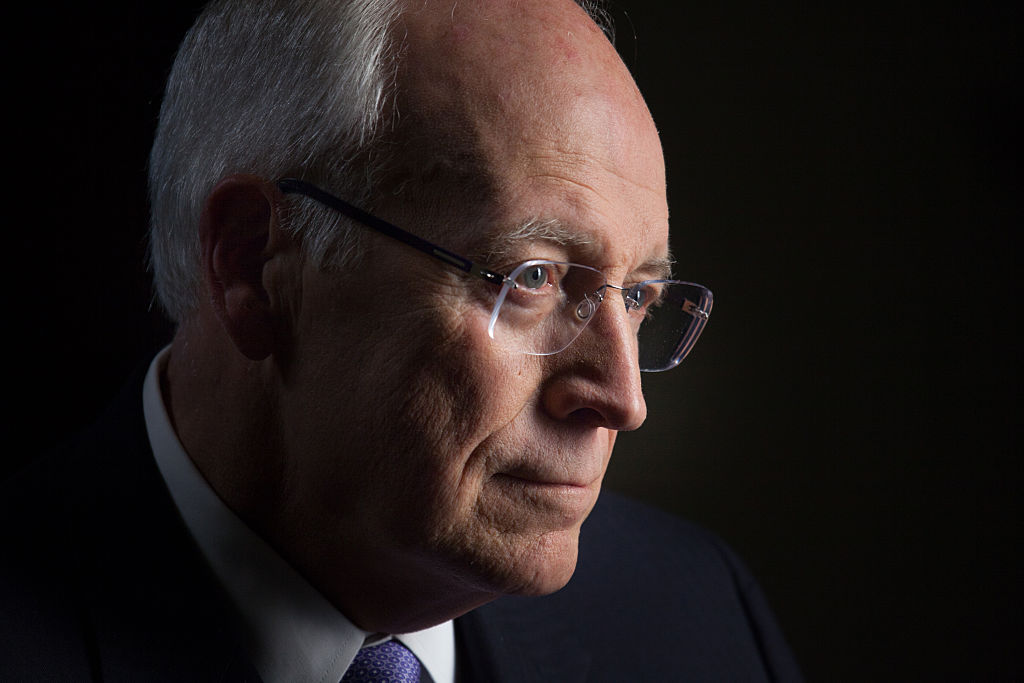

It was the same argument President George W. Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney and defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld made week after week in the year and half leading up to Operation Iraqi Freedom: Saddam is a madman armed with weapons of mass destruction (those weapons, of course, didn’t exist), and the US couldn’t afford to sit on its heels and wait for “the smoking gun to become a mushroom cloud.”

We later learned, during Saddam’s interrogation in US military custody, that the Iraqi dictator wasn’t as much a madman with his finger on the trigger as he was a terrified schoolboy who wanted to avoid revealing Iraq’s military weakness to next-door Iran, a neighbor he’d spent nearly a decade fighting to a stalemate in the 1980s.

North Korea’s Kim Jong-un and Syria’s Bashar al-Assad have also been categorized as lunatics operating without an ounce of restraint.

As national security advisor, H.R. McMaster took those claims to the extreme by recommending a military strike on a nuclear-armed Pyongyang in order to prevent North Korea from acquiring a workable intercontinental ballistic missile. The reason, presumably, was because McMaster believed Kim would eventually use a nuclear-tipped ICBM to destroy US cities like Los Angeles and Chicago (how Kim could do this without losing his own life, the lives of his extended family and the annihilation of his country was never explained).

Fortunately, President Trump ignored McMaster’s reckless advice, which would have precipitated the very nuclear crisis the former general was supposedly concerned about. The US, however, did take military action against Hussein, Gaddafi and Assad. The first two lost their regimes as well as their lives, opening up Iraq and Libya to the internecine spasms, terrorism, violence and societal cleavages both countries experience to this day. The third, Assad, was fortunate to have what Hussein and Gaddafi never did: a support base within his own country whose future was directly tied to his own fate and security partners (Russia and Iran) who were more invested in keeping Assad afloat than the US and its Gulf Arab partners were in deposing him.

As the bloodshed gets worse in Ukraine, we can expect more op-eds and television segments comparing Vladimir Putin to the Devil Incarnate, a person devoid of any reason and immune to rationality. But history shows that labeling foreign leaders as crazy, however despotic and disgusting their behavior, sends us down a rhetorically slippery slope. It makes interventions easier to justify, renders the possibility of some face-saving diplomatic resolution all but impossible (who, after all, would negotiate with a crazy person?) and dumbs down the conversation. There’s also a pretty good chance it’s the wrong diagnosis.