Vladimir Putin’s brutality in Ukraine is only going to get worse. The Ukrainians have fought valiantly, far better than anyone expected, but then that only means the Russians will have to up the slaughter in the coming days. As for Putin, he’s reportedly fuming over his army’s setbacks, threatening reprisals, while hunkering down in — I’m not making this up — his “mountain lair” deep in the Urals.

If that makes Putin sound like a Bond villain, then that’s just one of the many images of him that’s emerged in recent days (the most popular is Putin as Hitler). The seemingly insane nature of his Ukraine invasion has left observers grasping for a reference point. Is Putin addled by cabin fever? Under the sway of extremists? Mentally ill? Who is this Vladimir Putin anyway? It’s a question that, given the Russian dictator’s (carefully cultivated) enigmatic nature, can be difficult to answer.

Putin is, first and foremost, a KGB man, a security bureaucrat from the old Soviet Union. And if you read the literature, you’ll find there’s one story about him that comes up time and again. It was December 1989, the Berlin Wall had just come down, and the USSR was rapidly crumbling. East Germany in particular had devolved into anarchy, and a furious mob was approaching the KGB facility in Dresden where a young Vladimir Putin was stationed. Worried the building would be overrun, he phoned for military help, only to be told he was on his own. “Moscow is silent,” said a voice on the other end.

Putin, fluent in German, was ultimately able to persuade the mob to leave. But more than one of his biographers has said this experience haunted him. “I realized the Soviet Union was ill,” he later recalled. “It was a fatal illness called paralysis. A paralysis of power.” As the Soviet empire gave way to the huk-yukking failures of the Yeltsin years, as the policy of “lustration” saw KGB personnel purged throughout much of the former USSR, Putin’s distrust of democracy, disorder, mob rule only deepened.

It’s here that a certain type of conservative sometimes finds himself quietly sympathizing with Putin. Conservatives, after all, aren’t always wild on democracy either, and they detest nothing so much as the unruliness of the mob. They also tend to place their faith in institutions rather than individuals, which is Putin’s view exactly. And they pride themselves on being realists rather than idealists, perhaps warming to Dostoyevsky’s observation that “We, in Russia, have no fools,” by which he meant not idiots but romantics. Conservatives are not supposed to be romantics. And while Putin is many things, a romantic is not one of them.

What this view misses, however, is what all this cold-eyed realism seeks to achieve. Putin isn’t some postliberal Charlemagne using the power of the state to safeguard Christian traditions. The institutions he reveres aren’t church and community but the old Soviet security forces, the ex-KGB. It was by restoring their status and infrastructure, giving them close to absolute power, that he was able to cement power in a way Yeltsin never could. Putin is the ultimate deep statist. His regime was best summed up by Russian-American dissident Masha Gessen as a “tyranny of bureaucracy.”

This is the politics not of Donald Trump but of James Clapper. And because the security state has been given such extraordinary power in Russia, those in its favor have been able to strip-mine their nation’s key industries for their own benefit. Putin’s Russia is a haven for the obedient civil servant and the ravenous kleptocrat, and a reminder of how easily one becomes the other. This exalting of government is then passed off as civic order, the only way to keep the howling mob at bay.

Yet even then it’s too simplistic to say Putin is just a bureaucratic chess-player. The man is cold-eyed, yes, cynically clinging to power through whatever means necessary, showing no regard for basic freedoms or civilian casualties. But his nostalgia for the KGB dovetails into a greater nostalgia for the days of Russian empire. There’s a reason he called the collapse of the Soviet Union “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe” of the twentieth century. He’s a dreamer in his own right, not of democratic freedoms and self-determination but of the restoration of his nation’s might and scope.

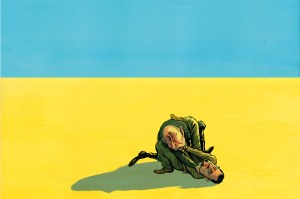

Until now, that dream has been, for the most part anyway, checked by his managerial realism. Putin has launched military incursions before — into Chechnya, South Ossetia, Crimea — but these have always been relatively limited affairs, not attempts to annex an entire sovereign country. With Ukraine, this caution has evaporated. Putin, like any good intelligence agent, is obsessed with control, yet by steamrolling westward he’s invited in chaos. His careful plan of attack has been scrambled by the scrappy Ukrainians. His management of the Russian economy has been shattered by sanctions. Civic order has given way to antiwar unrest across Russia.

What caused this change? Perhaps Putin grew paranoid under quarantine or felt threatened by NATO or was still smarting from the Maidan revolution back in 2014. Whatever the case, the ultimate deep statist has now been thrust into the sunshine for all to see. No one, conservative or otherwise, should admire this drab paint stick of a man, this gray squelcher of creativities and lives. May the Ukrainian and Russian peoples finally put an end to his meal ticket.