In 1867, a pair of US Army personnel stationed at Ft. Wallace, Kansas came across a curious discovery: the bones of what appeared to be an enormous, fossilized reptile. Its vertebrae were delivered to paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, who recognized them as belonging to the order of seafaring beasts known as plesiosaurs — but belonging to a whole new species. (For those in need of a more contemporary cultural reference, plesiosaurs are the kind of extinct animal that proponents of the Loch Ness Monster insist is still paddling around in Scotland.) Cope, one of the preeminent fossil-hunters of his day, excitedly rushed to chalk up this new discovery to his professional bar tab. He named the creature Elasmosaurus platyurus and hastily prepared for its debut to the scientific world. Perhaps too hastily.

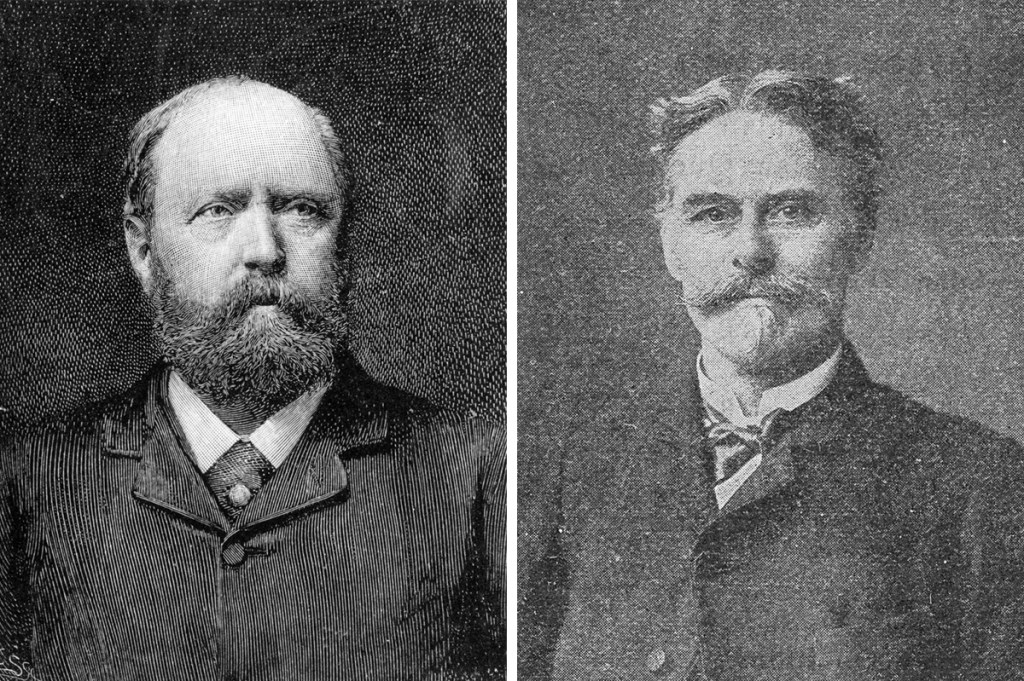

As it turns out, Cope had constructed the Elasmosaurus skeleton in a way that put the poor creature’s head on the wrong end of its body. This caught the attention of fellow paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh, who committed an unhealthy amount of energy to ‘cancelling Edward Drinker Cope, using the error as ammunition in his campaign to destroy Cope’s reputation. Cope was reliably eager to return the favor in defaming Marsh. Their rivalry has become known as ‘The Bone Wars. To casual fans of dino-digging history, Cope and Marsh are known as much for their attempts to wreck one another professionally as for their actual fossil discoveries. They were even the subject of an episode of Drunk History.

Historical context makes the current ‘cancel culture hullabaloo — which, by the way, the general, non-Extremely-Online public doesn’t give a hoot about, if a recent Politico poll is any indication — seem rather quaint. The Victorians were much better at canceling than we are. Jerome Meckier’s 1987 book Hidden Rivalries in Victorian Fiction describes Charles Dickens was routinely trashed by contemporaries who thought his writing sensationalized poverty to further his political aims. Oscar Wilde had a dizzyingly complex rivalry with the Marquess of Queensberry that is perhaps easiest boiled down to public smears like ‘the tower of ivory is assailed by the foul thing’. Allies of Thomas Edison attempted to ruin his rival George Westinghouse in a gruesome campaign of stunts where Westinghouse’s alternating-current electrical technology was used to fry a series of animals like dogs and horses and permanently associate it with the electric chair.

There’s something to be learned from this mess of newspaper snipes and electrocuted horse: ‘cancel culture’ is as old as the history and development of human ideas. We have always been clawing at a visceral, lizard-brain need to discredit our ideological opponents in the course of establishing our own intellectual prowess. Maybe this is something we all ought to accept before we declare that either cancel culture isn’t real, or that cancel culture is somehow something new and insidious.

If anything, cancel culture has gotten milder. These days, your enemies don’t plan on keeping your preserved remains in a jar on their desk as a reminder of their triumph over you. That really happened: when paleontologist Gideon Mantell died by suicide in 1852, his rival dinosaur sleuth Richard Owen not only usurped credit for some of Mantell’s discoveries, he kept Mantell’s pickled spine on display at the Royal College of Surgeons in London. Paleontologists appear to be a gruesome scheming bunch: perhaps they snorted too much dust from dinosaur bones.

These extreme attempts at discrediting others were not the domain of sociopaths or the equivalent of 4chan incels. They were committed by respected scientists and innovators. Whatever went on in the halls of the Royal Society of London would probably make contemporary disputes between Quillette and Vox writers look like a schoolyard game of dodgeball. Now, when someone like Sen. Kelly Loeffler claims she was ‘canceled’ — last I checked, she was still in the Senate — it looks like a cynical attempt to play the victim.

Let’s also not forget the less colorful incidents throughout history of individuals whose rivals and enemies attempted to socially discredit them through allegations of homosexuality communism or witchcraft — all of which are pretty cool these days. Noam Chomsky and Salman Rushdie signed the now-infamous ‘Harper’s letter’ — their work has legitimately put their lives in danger. Human dissent over ideas and ideology has always been accompanied by a dark undercurrent.

Of course, Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh did not have the ability to corral social media armies to do their bidding and support them in their mutual attempts at professional ruin. A common thread that runs through all the epic yarns of Victorian cancellation is the idea that everyone could be just as awful to one another as they possibly could. The tactics, as far as I can tell, don’t seem to have been questioned. But in today’s era, there is a serious current of ‘acceptable for me but not thee’.

***

Get a digital subscription to The Spectator.

Try a month free, then just $3.99 a month

***

Take this talk at last year’s TED event, actor and filmmaker Rafael Casal took the stage to talk about a well-meaning social media campaign over the ouster of a black actor in a Broadway production to make way for a better-known white actor — a campaign that ultimately ended the show’s run. It got ugly, which he acknowledged. ‘Our messy moments online are not just a mess, but evidence of work being done to protest the injustices that are long overdue for some volume,’ Casal said in his talk.

Something tells me that Casal and his ideological allies would disapprove of the same aggressive social media lobbying tactics if they were deployed by the MAGA hat crowd. That’s the problem with 2020 cancel culture: everyone insists it’s OK if they do it, and it’s nonexistent otherwise. And everyone has access to eager like-minded followers at the click of a button.

At least in the Victorian era, brutal cancel culture tactics were just a fact of life. You know, like rats and cholera.