Combatants within our nation’s political class never suffer for lack of insults — and in recent years they’ve taken to hurling back and forth a particular aspersion with increasing frequency: “un-American.” In recent weeks we’ve heard pundits and politicians declaim that it’s un-American to blame gas prices on Joe Biden, to tax billionaires, to let states decide their own abortion laws, to oppose admitting Ukraine to NATO, to forbid sex-change surgeries for ten-year-olds, and to treat Disney like any other Florida corporation. Still others have declared “whiteness,” the NFL draft and racial disparities in student debt to be un-American. Former acting director of national intelligence Richard Grenell apparently believes that even Article II, Section 1 of the US Constitution is un-American.

Though you wouldn’t know it from watching cable news, the plural of anecdote is not data, so consider the numbers. According to the massive NOW Corpus database of newspaper and magazine text, the use of “un-American” is on the rise. We’ve gone from 326 uses recorded in periodicals in 2010 to 1,605 last year, and we’re on pace to break that record this year.

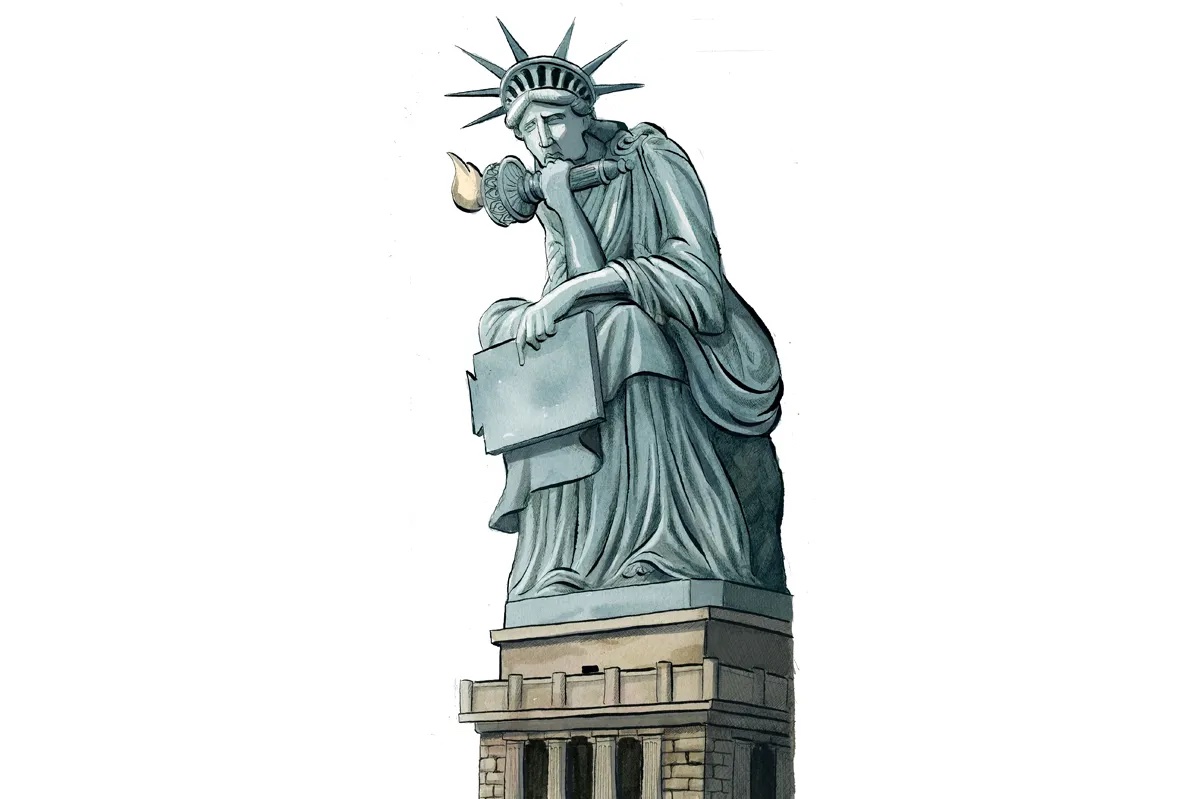

I want to read this as a backhanded kind of patriotic resurgence, but most likely it’s just an example of what happens when kids in a rock-throwing fight snatch up whatever lies close at hand. No matter the cause, the growing popularity of this calumny among our nation’s pundits and politicos drips with irony. After all, it is they who are the least American of any of us.

Their investment in politics and ideology, for example, puts the members of America’s political class well outside the American mainstream and ethos. Just nine percent of Americans describe themselves as extremely liberal or conservative, and most people’s policy preferences — even when we contrast supposedly “red” and “blue” congressional districts — aren’t all that far apart on most issues. Activists and partisans on left and right, on the other hand, gladly describe themselves in starkly contrasting ideological terms. Studies of party delegates and donors further substantiate how far apart their views and policy demands are,not just from their counterparts on the other side, but from the bulk of Americans, who cluster, on issue after issue, at the center-right.

What we’re seeing isn’t just a divergence in policy preferences between the political class and the rest of America. It’s a chasm of values. Members of the political class derive a substantial part of their meaning from elections and policy wins, comporting themselves year in and year out the way rabid sports fans only behave on game days. Ninety-seven percent of Americans, in contrast, choose something other than political party when asked to name the most important factor in describing who they are. While nearly all Americans point to their families, their religions, and their occupations as being most essential to who they are, our political class — the people bandying about accusations of un-Americanness — defines itself chiefly by partisan allegiance.

These people are not normal. They are, well, un-American.

Nearly 200 years ago, Alexis de Tocqueville discerned how low-key ideology was a characteristically American quality. He wrote about how his fellow Frenchmen, in contrast, were prone to spasmodic bouts of shallow nationalistic fervor, “a sort of joy in surrendering themselves irrevocably to the arbitrary will of the monarch.” Americans were certainly patriotic, but this wasn’t rooted in allegiance to a party or ruler, it was the result of local cooperation and self-governance. American patriotism stemmed not from ideology so much as from the many cross-knitted community bonds that emerge among a free people for whom politics is not a high priority.

The way this plays out in modern America is that most Americans have at least a few friends who vote for the other party. This shouldn’t surprise us; it’s the American way. Strong partisans, on the other hand, feel significantly greater animosity toward people from the other party, and count few of them as friends. They simply care far more about politics than do the vast majority of Americans. It’s personal for them.

“Un-American” is an accusation that’s likely to continue zipping through the air so long as pundits believe it carries a sting. Maybe that’s a good thing, insofar as it indicates that the members of our perpetually sniping political class have found something they agree on, which is that it’s bad to undermine the American ethos. In this respect, at least, they not only speak the truth with one voice, but prove it.