Bipartisanship is a word used too frequently, and seldom ever found in the swamps of Washington, DC.

On Tuesday, Congressman David B. McKinley, Republican from West Virginia’s former First District, named “one of the most bipartisan members of Congress,” battled Congressman Alex Mooney, representative of the former Second District. The two were competing to represent West Virginia’s newest congressional district, which stretches from Jefferson to Mason counties. The latest congressional map came as a result of 2020 census data that revealed a loss of population in the Mountain State.

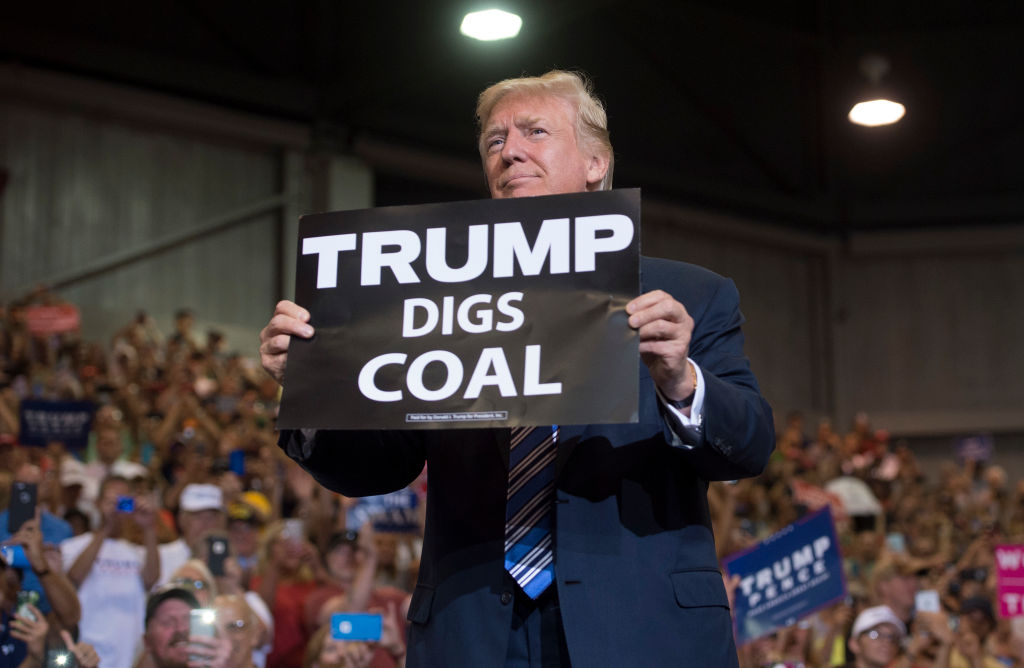

It was Alex Mooney who scored the win and secured the Republican nomination. Though that wasn’t shocking for political aficionados who recently watched Hillbilly Elegy author J.D. Vance win the Republican primary for Ohio’s Senate seat. Mooney and Vance were both endorsed by former president Donald J. Trump, and are both controversial.

In 2021, Mooney was the subject of accusations referred to the Office of Congressional Ethics. The OCE’s investigative report found that the congressman had used campaign funds for fast food and family vacations totaling over $40,000 in unreported spending. As a result, a second investigation with broader parameters was also opened and referred to the House Ethics panel. It’s expected to announce its course of action on or before May 23.

McKinley didn’t go down without a fight. The six-term congressman received support from West Virginia governor Jim Justice, who was supported by President Trump in 2020, as well as Democratic senator Joe Manchin, who chimed in with an ad released just days before the election.

“Alex Mooney has proven he’s all about Alex Mooney, but West Virginians know David McKinley is all about us,” said Manchin, hoping to corral moderates in McKinley’s favor.

Justice, meanwhile, even said that Trump had “made a mistake” by backing Mooney. “Now I don’t have a dog in the fight against Alex Mooney in any way,” said Justice. “But I can tell you I have been close with the Trump family, and I am friends with Trump. From time to time, he can make a mistake. And this time, he has made a mistake.”

Yet Justice and Manchin failed to bring McKinley across the finish line. The lesson? Trump’s reign as kingmaker in West Virginia has not yet come to an end.

Do as I say (not as I do)

Earlier this year, I wrote a piece on the tenacity of West Virginians, as we defended our home against Bette Midler’s bigoted Twitter attack. We disavow those who tell us what to do, how to live, and what our worth is. But we’re also quick to make exceptions.

Both Congressman Mooney and President Trump are out-of-staters. McKinley, Justice and Manchin, on the other hand, have a deep-rooted history in our Appalachian valleys.

So why is it that a lifelong West Virginian, with endorsements from lifelong West Virginians, couldn’t pull it off? Perhaps it all boils down to a single vote.

Last January, Congressman McKinley voted to support a highly criticized $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill, backed by President Joe Biden. Mooney called the legislation a “socialist spending spree.” He told Metro News, “It also had liberal pet projects in there, like vehicle charging stations for electric cars, a pilot program for vehicle miles traveled.”

McKinley pushed back. “This was an opportunity that was only going to come around one time,” he said. “We’ve waited now eleven years to get this.”

After Biden signed the infrastructure bill into law, a White House press release projected that the following investments would flow to West Virginia:

- $3 billion of federal aid for highway apportionment

- $506 million for bridge projects

- $100 million for internet access expansion

- $141.9 million to plug orphaned gas wells

- $140.7 million to reclaim abandoned land mines

- $1.25 billion to the Appalachian Development Highway System

- $200 million to complete Corridor H

That’s a grand total of nearly $5.4 billion. Yet what was celebrated by some West Virginians created consequences that the McKinley campaign could not overcome.

The finch, the sparrow and Byrd

A similar sentiment can be drawn from Senator Robert C. Byrd’s legacy. Notorious for his bringing home of federal dollars, Byrd’s gift to West Virginia was a 2:1 ratio: the state now receives $2 for every $1 sent to the federal treasury.

When he became chair of the Senate Appropriations Committee in 1989, Senator Byrd promised to haul in $1 billion for West Virginia. Metro News estimates the continued appropriations initiated by Byrd have totaled over $10 billion. That means McKinley was able to secure half of what Byrd was able to collect in just one year.

Yet as an op-ed by the writer Rebecca McPhail suggests, an influx of federal monies has consequently furthered an “injured self-image,” feasibly explaining the state’s rejection of McKinley.

In a campaign ad, Mooney asserted that the trillion-dollar infrastructure bill was one a conservative simply wouldn’t support. He turned McKinley’s penchant for bipartisanship into a weakness, and it worked. He even laid the entirety of the expensive bill at McKinley’s feet. “Biden’s trillion-dollar spending bill was dead until McKinley resurrected it,” the ad claimed.

McKinley was one of thirteen Republicans to vote for the bill. According to FiveThirtyEight, McKinley was in harmony with President Trump’s positions 92 percent of the time, while Mooney was 86.7 percent of the time.

The Trump Train rolls on

In the end, the election afforded an insight into the ever-changing sides of a relatively new, red West Virginia. In 2017, alongside President Trump, Governor Justice announced his registration change after being elected as a Democrat in 2016. Yet in 2018, when Attorney General Patrick Morrisey took on incumbent Senator Joe Manchin with a Trump endorsement, the state rejected “New Jersey outsider” Morrisey in favor of Fairmont native Manchin. Seemingly, the electorate still believed the Democrat could bring bipartisan victories to West Virginia.

In stark contrast, bipartisanship failed this time around, after the 2020 election yielded more political division. In the 2022 midterms, Trump endorsements are carrying more weight, at least so far. West Virginia has made it clear they’re all aboard the Trump Train, wherever it may lead. No moderates allowed.