America is unraveling into an unhappy confederation of hostile tribes. Extremists on the right are murdering Jews in synagogues and African Americans in churches. The woke left is bullying us into a neo-segregation in which we’re judged by the color of our skin. We’re too obsessed with economic growth to recognize that the rising tide has swallowed entire regions. We’re too proud of our tradition of immigration to admit the failures of assimilation.

At a time of such angry division, what can bind up our wounds and bring us together as a nation?

A renewed patriotism would be a step in the right direction, but it’s not enough. Patriotism asks us to love our country. But what we need now is more than love of country. We must love our fellow citizens. We must feel a connection to each other that is deep enough to overcome our superficial differences and profound enough to motivate mutual sacrifice. We must internalize the reality that our futures are inexorably — even mystically — intertwined.

What we need today is a renewed American nationalism.

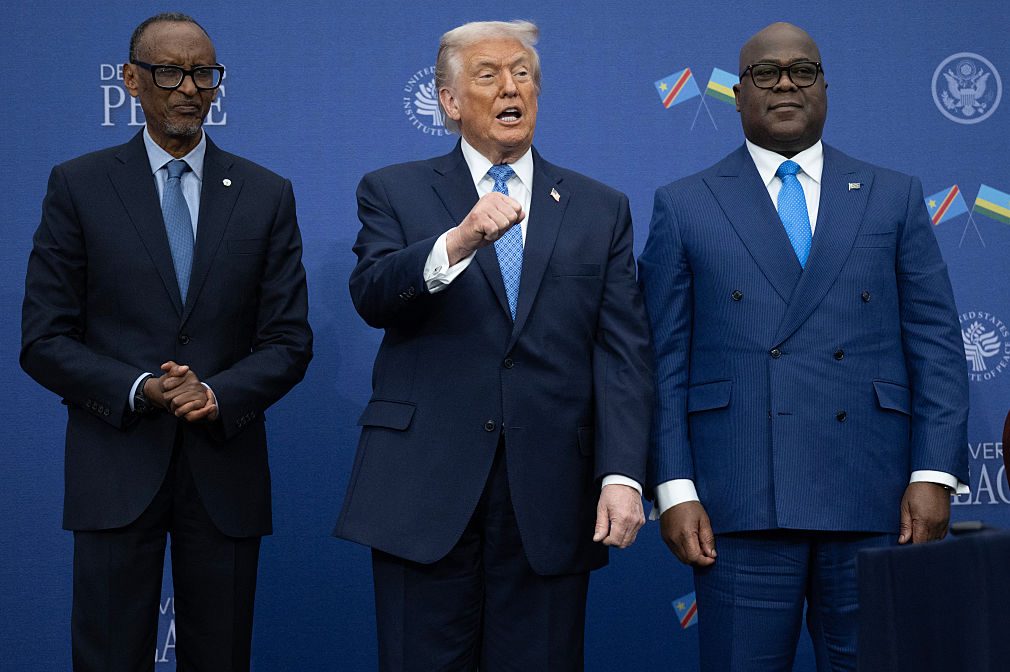

Yes, nationalism. Now that President Trump has declared himself a nationalist, this ideal is the subject or heightened interest and preemptive attacks. While the term is still quite vague, critics have rushed to fill it with the content of their worst nightmares. They insist that by nationalism we mean white nationalism, nativism, blood and soil. Opportunists on the extreme right are only too happy to oblige as they rush to tap this potent political energy to fuel their own racist ends.

Such efforts are bound to fail. In America, any effort to build a nationalism grounded in race will be crushed by the weight of our diversity and overwhelmed by the power of our ideas. While there have been great sins and shortcomings along the way, our leaders set us on a path that guaranteed that our American identity would eventually transcend blood and clan. At the same time, they set forth the principles that could unite so diverse a people. There is a deep American nationalist tradition. While multiple American leaders have contributed to it, three giants stand out from the rest: Alexander Hamilton, Abraham Lincoln and Theodore Roosevelt.

All three of these leaders envisioned a nation into which immigrants from any country could come and assimilate. But each believed that this assimilation required something more profound than assent to a set of abstract ideals. They describe instead an almost mystical process by which the foreign born would be transformed into Americans over the course of years spent ‘dwelling among us’ (Lincoln); ‘acquiring American attachments’, and ‘imbibing the spirit of our government’ (Hamilton).

All three believed that this energized conception of American identity would demand — and inspire — a greater level of mutual responsibility. Each appealed to this vision to motivate the military sacrifices their times demanded. And each invoked these ideals to vindicate the economic nationalism that our times continue to demand. This sometimes meant paying tariffs to protect domestic manufacturing from foreign competitors. It more often meant spending public funds to build the infrastructure and industries that would give all Americans an equal opportunity to rise, regardless of region or class.

In this time of great division, we can learn much from a prior era of far greater division. Abraham Lincoln became president as the Civil War loomed. At that perilous juncture, he reached the height of his eloquence in elaborating a vision of what could yet hold us together. Lincoln closed his First Inaugural Address with this famous formulation of American nationalism:

‘The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.’

Here Lincoln suggests that what unites us goes deeper than ideas to include a shared history of struggle and sacrifice. Our American soil has been the burning ground upon which events transpired that forever bind us to one another. Lincoln never believed that one must be born on this soil to become an American son or daughter. But he certainly suggests that we need a deeper communion with it to unite and inspire us. Only those who know our history can develop this requisite memory. Only those rooted in our soil can feel these chords reverberating down to the present day.

An energized American nationalism will demand as much from the native born as from its newcomers. If nationalism is to be more than a slogan, we must understand that national attachments, like all others, come with profound responsibilities. We must place the interests of our fellow citizens above those of people who live beyond our borders and — at times — even above our own personal interests. As Americans grow increasingly alienated from one another, a renewed American nationalism offers us a shining path back home.