If conservatives interpreted Barry Goldwater’s defeat in 1964 the way Trump supporters are being told to interpret the 2022 midterms, there would be no conservative movement today. Of course, the 1964 election was an actual defeat, while this year’s elections were an advance for the new Republican right, which succeeded in its first task — gaining power in the GOP — and has strengthened its hand in Congress. The right has picked up a Senate seat with Ohio’s J.D. Vance, and Republicans look likely to control the House of Representatives come January. The GOP won the majority of votes cast in House races, nearly 52 percent overall.

The official narrative of the election is meant to drive the right to suicide. Democrats, NeverTrump ex-Republicans, and critics of the populist right who remain in the GOP have all blamed Trump voters for the party’s failure to take the Senate and claim a commanding margin in the House. Donald Trump himself was not on the ballot, but he made endorsements, and voters who followed those endorsements chose weak candidates, the story goes.

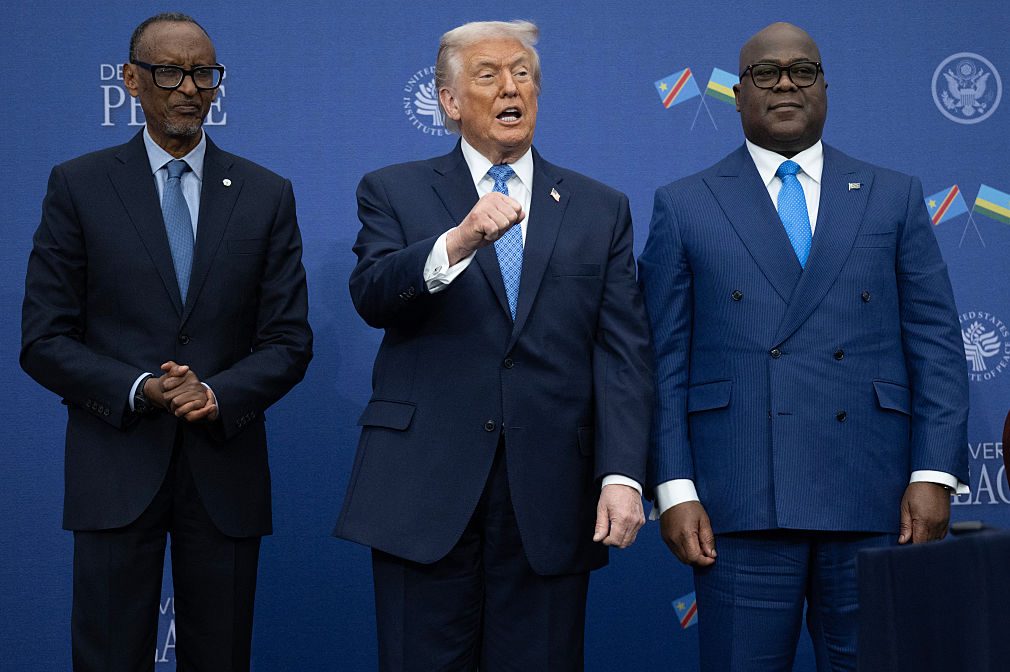

The anti-right narrative is a remarkable thing: when a candidate Trump supported lost, like Mehmet Oz in Pennsylvania, it was Trump’s fault; when a candidate Trump opposed lost, like Joe O’Dea in Colorado, it was Trump’s fault. When a candidate Trump supported won, such as J.D. Vance in Ohio, pundits discounted the victory; when a candidate Trump opposed won, such as Brian Kemp in Georgia, the same pundits found it enormously significant. Ron DeSantis’s nearly 20-point margin of victory in Florida, a big win for the right, was mostly hyped as a defeat for Trump, even though Florida is Trump’s home base.

In light of all the other commentary, it should be clear to voters of the right what liberals are trying to do: they prefer DeSantis to Trump, and by presenting the midterms as a defeat for the populist right, they hope to persuade DeSantis to shift away from the right if he runs for president in 2024.

But before DeSantis, or any other Republican, accepts that narrative, he should ask himself what the 2022 results really say about the momentum of different ideological blocs within the GOP and in the country as a whole. The first thing to notice is that incumbents won last Tuesday no matter what their ideological tilt — not a single sitting senator or governor lost. Moderate Republican incumbents like Ohio’s Mike DeWine won; liberal Democrat incumbents like Michigan governor Gretchen Whitmer and New York governor Kathy Hochul won; libertarian-leaning Trump-friendly Republican incumbents like senators Mike Lee and Rand Paul won; and DeSantis himself, the right-wing incumbent governor of Florida, won.

The flip side tells the same story: challengers of all stripes, right-wing, moderate, or liberal, almost always failed. If the 2022 election was meant to signal a rise in anti-Trump sentiment, the original NeverTrump candidate, Evan McMullin, shouldn’t have lost to Mike Lee in a double-digit blowout. Utah, after all, is the least friendly red state in the country for Trump’s brand of politics, and McMullin, who ran an independent campaign for president in 2016, ran against Lee this year on a platform entirely focused on tying the senator to the former president. He still lost by nearly 14 points.

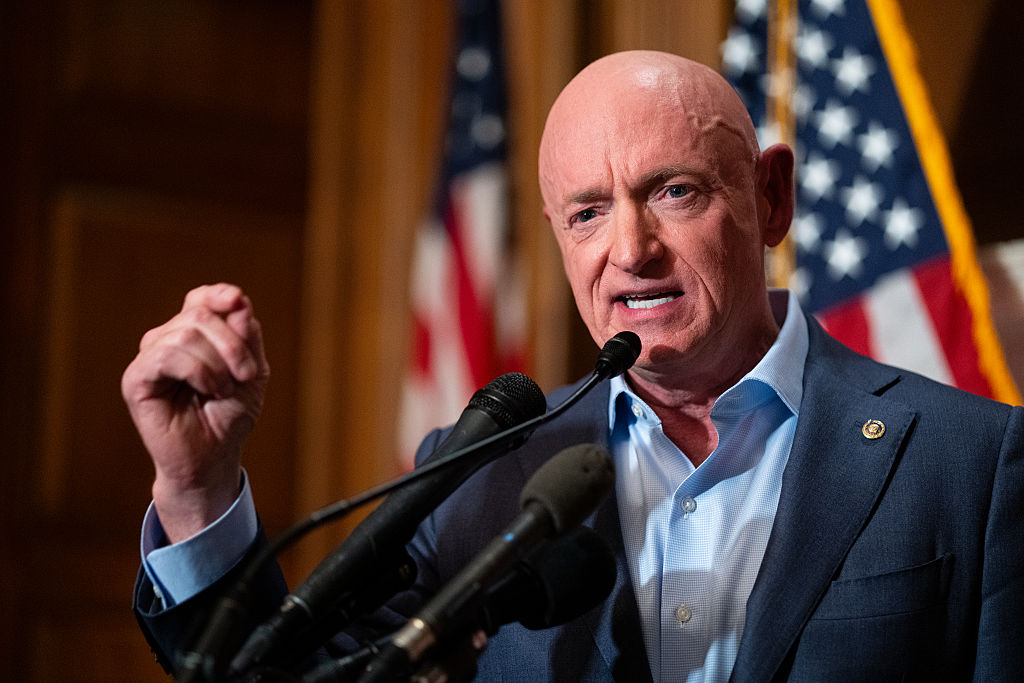

Compare that dismal performance by a NeverTrump champion to the narrower loss by a Trump Republican like Blake Masters to an incumbent Democrat senator. As a former astronaut, Mark Kelly has the kind of résumé most politicians would kill for, and as senator he has had no particular scandals to his name. He is the kind of politician who could be expected to cruise to re-election any year, particularly in a cycle friendly to incumbents. But Masters, a 36-year-old first-time candidate, came about five points short of knocking out Kelly. Anyone who looked at this race without any knowledge of the “official” narrative would conclude that this political neophyte was a phenom, a first-time loser but a long-term winner, with the brightest of futures. A candidate like that would tell a neutral observer something important about the direction of American politics.

Two of this year’s battleground open-seat Senate races also sent a clear signal that differs from the pundit-class consensus. Where there was no incumbent in these battlegrounds, populism was the victor. And where voters were given a choice between right-wing and left-wing varieties of populism, they chose the right-wing kind. In Ohio, both parties fielded candidates with appeal to working-class voters, the Republican J.D. Vance, known for his memoir Hillbilly Elegy, and the Democrat Tim Ryan, a politician often named as an exemplar of how Democrats can appeal to blue-collar voters who increasingly trend Republican. Vance won by six points.

In Pennsylvania, a left-wing populist Democrat with experience as the state’s incumbent lieutenant governor, John Fetterman, beat a Trump-endorsed but not-populist Republican, the television celebrity doctor Mehmet Oz. Fetterman was certainly weakened by a recent stroke, yet he was exactly the right candidate to cut into Republican attempts to win working-class and less educated voters. And Oz, despite the Trump endorsement, was hardly the right candidate to outbid Fetterman for those votes. A Vance-like candidate in Pennsylvania would have done better than Oz, and although Pennsylvania is less Republican than Ohio, a candidate like Vance could probably have beaten Fetterman.

Going into the midterms, I was as wrong as everyone else about the mood of the electorate. Midterms usually see big gains by the party out of power in the White House, and amid inflation and rising crime, the Democrats seemed to be doomed. I wrote an op-ed for the New York Times arguing that Republicans were now the party with entrepreneurial initiative, and the risks they were taking would pay off. In any event, the payoff was much smaller than expected — for now. The country responded to all the uncertainty and misery of recent times not by gambling on change but by sticking with incumbents of both parties and all ideological complexions. The public chose to punt on making decisions this election, leaving Congress closely divided.

That’s not a loss for the right; it’s a postponement. And no rival faction of American politics scored a lasting victory on November 8. Adding John Fetterman to the Senate does nothing to rejuvenate the party of Joe Biden, and the loss of Tim Ryan — who did have promise as a potential national figure — is more significant for the Democrats’ future than Fetterman’s victory. The 44-year-old Ron DeSantis and the 38-year-old J.D. Vance, by contrast, do strengthen the future of the Republican right. Moderate Republicans did well with incumbents, just as everyone else did, but gained no new momentum from the re-election of governors like Mike DeWine. And Evan McMullin’s rout shows that NeverTrump politics has nothing to look forward to even in Mitt Romney’s Utah.

Populism and the right are still advancing in American politics. This proved to be great news for Ron DeSantis last Tuesday, but it is also good news for Donald Trump, who remains the father of right-wing populism. What he began in 2016 continues to grow. It took the GOP by storm in this year’s primaries and has made inroads into Congress even at a time when voters are taking no risks. The present knife’s-edge balance in legislative and presidential elections will give way to decisive results before long. Which side has the energy, drive, confidence, and courage to claim the future — no matter how long it takes?

The fact that the right may be in for a bruising battle between Trump and DeSantis is only proof that there is a prize here worth fighting for, and it’s more than just the 2024 Republican nomination. The lesson of this year’s midterms, however, is not to be impatient. The timetable for change in American politics may not be what anyone expects, but the force of change lies firmly on the right.

Daniel McCarthy is the editor in chief of Modern Age: A Conservative Review