Russia has invaded Ukraine, and the images are all over the news. CNN has gone to round-the-clock coverage of bombs falling near Kyiv, refugees pouring into Hungary, Putin’s war machine rolling down a misty highway. We’re outraged by this, roused to action, as we righteously hang a blue-and-yellow Ukrainian flag off the porch and learn to spell the names of places like Kherson and Mariupol. The West, listless and fractured, seems suddenly united again as opposition to Russian imperialism grows and…

…and it’s summer. The weather is warm and a gentle breeze is tinkling through the chimes. The kids are off from school, horsing around the kitchen, and the lawn isn’t going to mow itself. The TV is set to a relaxing YouTube ambience, while a final inventory is being taken for the upcoming beach vacation… is one bottle of SPF-40 enough? Ukraine? Don’t we have enough problems to deal with? Inflation is out of control and filling the gas tank has never been more expensive.

So it’s gone with America’s attitude towards the war. Outside of a handful of foreign policy gurus and Eastern European diehards, few are closely following it anymore. The initial mesmerizing shock of the invasion has yielded to a kind of white noise, the sort we reserve for the myriad conflicts across Africa and the Middle East. Oh, right, that’s happening. Even the New York Times, which for weeks led with its Ukraine coverage, is these days more preoccupied with the pressing subject of whether Donald Trump is about to be thrown in a dungeon.

In fairness, it’s usually the case that we care most about those who are nearest. In Bleak House, Charles Dickens parodies those who obsess over foreign sufferings with the unnatural Mrs. Jellyby, who busies herself saving the Africans while her own children wallow in filth. Yet even allowing for this, America’s dissonance on Ukraine has been… weird. It’s had a kind of whiplash effect, with everyone ululating Ukrainian war chants one second and then seemingly forgetting all about it the next. That’s all the more unfortunate given that the Russians are in a stronger position today than they were four months ago. What explains this dramatic drop-off in interest?

A half-century ago, the Vietnam War was “the first television war,” as the names of the dead were regularly read on nightly newscasts and Walter Cronkite’s change of heart after the Tet Offensive had a seismic impact. More recently, some called the 1991 Gulf War the first video-game war, as American cameras showed Saddam’s tanks driving into crosshairs and then exploding. Of that conflict, Chuck Klosterman wrote in his book The Nineties, “It was as if the war were only fought by machines, devoid of human suffering or existential meaning.”

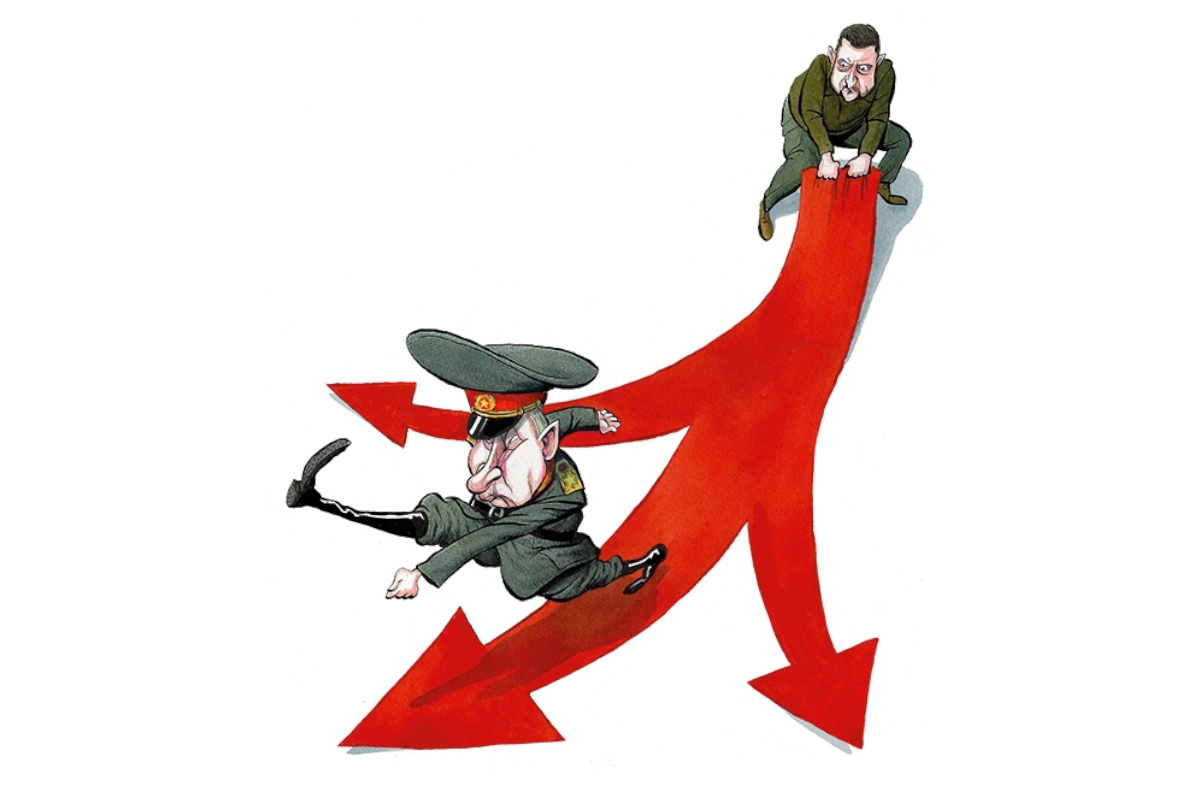

The Ukraine war isn’t quite like either of those. It’s more available, more visceral. It’s mediated through screens, but it doesn’t feel like a nightly TV show or a first-person shooter game. It’s more like our first streaming-service war, the kind of thing we might watch on Netflix or Hulu or (God help us) Peacock. Consider: the invasion began to a burst of attention. It was a multimedia phenomenon that sparked chatter across social media, discussions on YouTube, merchandise sales on Amazon (all those flags). Fans gushed over new celebrities, namely Volodymyr Zelensky, who provided plenty of bonus content in the form of interviews and video reports from the frontlines.

It was, in other words, like a new season of Stranger Things or Squid Game (remember that?); not just a TV debut but a cultural event. And then, as with those shows, its moment passed. People decided they’d bingewatched enough and transferred their attention elsewhere (sometimes to Stranger Things). CNN began airing a new serialized drama, which was a bit heavy-handed but whose Cassidy Hutchinson episode featured some of the best writing yet seen on prestige TV. The blue-and-yellow flags came down.

The problem was that the war never ended; if anything it has only grown more brutal. Some of this loss of attention is understandable: the conflict is taking place distantly and thus abstractly, at least from our point of view. But what made Ukraine unique was the intensity and universality of that initial sentiment, followed by the abrupt fade to black. Vietnam was a drip-drip-drip of pain; Ukraine was a bombshell that detonated all at once only to go silent.

It’s enough to make you wonder just how genuine we really were. It also makes you wonder about the increasingly blurred line between entertainment and reality. Our endless shows and immersive screens have made fiction seem sometimes like it’s real; the Ukraine war shows how it can work in the opposite direction. The conflict certainly felt real in the moment, yet the fact that everyone moved on so quickly suggests it was just a little bit unreal, contextualized as entertainment perhaps more than hard reality.

This is no way to look at the world. A war is not a bingeable drama. I’m not one who thinks America ought to keep throwing her military weight around. But the Ukrainians deserve more from us than just a night or two in front of the big screen.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2022 World edition.