The new year begins a new chapter in American foreign policy. For the first time since 2001, we are not at war in Afghanistan. More than that, we no longer have an architectonic strategy for our role in world affairs. We had one during the Cold War: to win it. And we had one afterward, too: a decade before 9/11, our policy elite had already committed to the idea that we must police the world for the good of the liberal international order. The lead-up to the first Gulf War was the opening paragraph of that chapter, the ignominious retreat from Afghanistan its last line.

Our policy mandarins have not changed their minds, but the world has changed too much for their grand design to have any meaning in 2022. The prospect of Russia or China becoming liberal and democratic now seems more remote than the prospect of, say, the United Kingdom cracking up, or the United States electing Donald Trump again in 2024. In 1991 or 2001, our foreign-policy elite could really believe that ejecting Saddam Hussein from Kuwait or the Taliban from Kabul was sufficient to uphold a world order. Does anyone believe that now?

Even die-hard interventionists cannot escape the fact that the kind of wars we conducted over the last thirty years are long, costly, unpopular, and at best yield messy, strategically dubious outcomes — if not outright disgrace. The quickest and cleanest, the liberation of Kuwait, became associated in popular consciousness with Gulf War Syndrome, gave Islamists abroad a rallying cause and led naturally, if not inevitably, to a second war with Saddam Hussein in 2003.

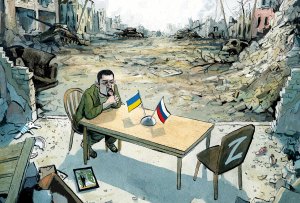

Small and tidy wars cannot preserve the liberal international order. So our hawks have begun to contemplate big wars again: a new Cold War, or maybe hot war, with China, or a war with Russia over Ukraine. The dovish experts, meanwhile, invest their hopes in one of two scenarios. One is the invincible logic of the free market and the inherent goodness of human beings. The other is isolationism-lite: trade will not save the world, so we must prepare for the liberal international order to fray, or even disintegrate. With oceans on either side of us and unthreatening neighbors to our north and south, we are insulated from the world’s conflicts, so long as we do not involve ourselves in them.

Compared to the dream of liberalizing the world through liberal means or the nightmare of fighting World War Three, isolationism-lite has the merit of sounding harsh but realistic. (Hard isolationism — less trade and tighter immigration controls — has few champions among the policy elite, though it is popular with outsider intellectuals on the right.) But its advocates overlook two critical facts, one of them a feature of the United States, the other a feature of politics itself.

The continental US may be safe from transoceanic invasion, but the US also includes some hard-to-defend Pacific islands, such as the state of Hawaii and the territory of Guam. These far-flung possessions, acquired in the nineteenth century, are hostages to the dominant power in the Pacific. China is a long way from becoming that power, but its journey would be considerably shorter if the US Navy were to pull back. The larger the role the PRC plays in the waters nearest to it, the sooner it can play a larger role in more distant seas. The vulnerability of Hawaii is not, of course, an academic question. If we want to prevent World War Three, we ought to take heed of how we got into World War Two.

The second rock upon which isolationism-lite founders is the political purpose of foreign policy. States and those who run them seek to preserve their regimes. They understand that a particular internal order requires certain external conditions, such as a degree of economic and ideological security. A country whose economy can be constrained by opponents is in existential danger — not of invasion but of regime transformation or collapse. Despotisms may be more resistant to such pressures than more commercial and popular forms of government. You need not become like them: all the pressure has to do is disrupt the order that you wish to enjoy.

The world beyond your borders can also apply pressures that can influence citizens and leaders at home and change how others treat you. A UK off the coast of a fascist EU would face a regime-level threat with or without the danger of invasion. This is why Putin’s Russia sows resistance to liberalism on its frontiers and beyond: the Kremlin understands the present liberal order as a threat.

The difficulty in setting a course for US foreign policy, and the reason why the course since the end of the Cold War has been a disaster, is that our choices are constrained by the needs of our internal order, which includes the values, passions and interests of our elite. Their motivations are the keys to our regime’s self-understanding, which in turn is the foundation of any US foreign policy. Until that self-understanding changes, our foreign policy will be misguided. The next chapter in our engagement with the world must be written in a different hand — but whose?

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2022 World edition.