Thursday’s decision by the Supreme Court that the Clean Air Act does not give the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) authority to proceed with President Obama’s Clean Power Plan is much more significant than the narrow grounds on which it was decided. The Clean Power Plan was already dead. It had been repealed and replaced by the Trump administration, decisions that were later struck down by a court of appeals.

Moreover, there is history between the EPA and the Supreme Court. In 2014, the Court ruled against the EPA’s rewriting of the Clean Air Act to facilitate its use as a tool of climate policy, which was already seen as “poor and probably unworkable” by officials in the Obama administration. “We expect Congress to speak clearly if it wishes to assign to an agency decisions of vast ‘economic and political significance,’” Justice Antonin Scalia famously wrote.

The Court also ruled that the agency had acted unreasonably with its mercury emissions rules, though the EPA boasted that despite this decision, investments meant that most power plants were already well on the way to compliance. Perhaps that attitude was a factor in the Supreme Court’s shock decision in February 2016 to stay the Clean Power Plan to prevent a repeat of the EPA’s workaround. As Justice Elena Kagan, writing for the court’s liberal minority, put it, “This Court has obstructed EPA’s effort from the beginning.”

Formally, the Court’s decision revolves around rival interpretations of Section 111 (d) of the Clean Air Act and what Congress meant by “best system of emission reduction.” Around 20 pages of Chief Justice John Roberts’s 31-page opinion for the court is taken up analyzing what he calls this “previously little-used backwater.” By “system,” did Congress mean a system modifying an existing plant’s emission performance? Or can “system” refer to the whole electrical grid or even a cap-and-trade scheme, as Kagan contends? Kagan’s brisk arguments demonstrate how a differently composed Court would have decided the matter.

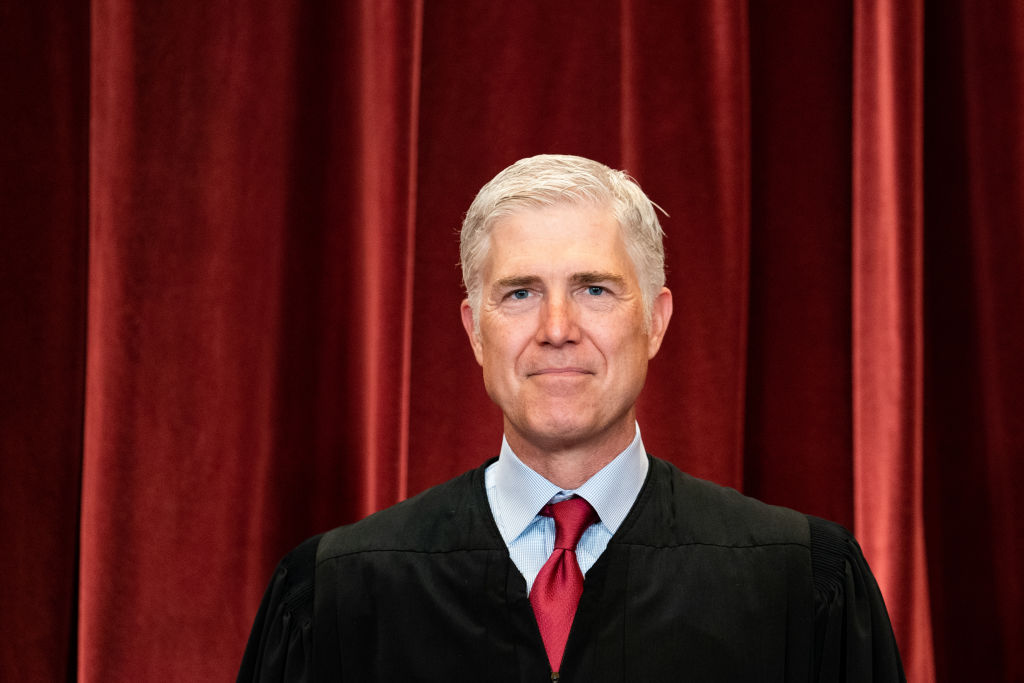

Important as these rival arguments might be, they function as kabuki theater for the underlying disagreement between the justices on the role and legitimacy of the administrative state. Although Roberts refers only once to the administrative state, it is never far from the surface. But the battle lines are made explicit in Neil Gorsuch’s concurrence and in the Kagan dissent.

For Kagan, the administrative state, in the form of the EPA, is indispensable to fighting climate change. Children born this year could see parts of the Eastern seaboard “swallowed by the ocean.” (In his dissent in the 2007 case that compelled the EPA to determine whether carbon dioxide is a pollutant, Roberts pointed out that the projected end-of-century sea level rise of 20 to 70 centimeters is similar to the average 30 centimeter and maximum 70 centimeter observed mapping error.)

According to Kagan, Congress delegates authority to organs of the administrative state because it is often “unreasonable and impracticable” for Congress to do anything else. Members of Congress often don’t know enough; “they rely, as all of us rely in our daily lives, on people with greater expertise and experience. Those people are found in agencies.”

Members of Congress also can’t know enough to keep regulatory schemes working across time. “Why wouldn’t Congress instruct EPA to select ‘the best system emission reduction,’ rather than try to choose that system itself?” “Congress,” Kagan answers, “knows that systems of emission reduction lie not in its own but in EPA’s ‘unique expertise.’” Of the Court stripping the EPA’s authority, Kagan melodramatically pronounces, “I cannot think of many things more frightening.”

Legislative history since passage of the Clean Air Act in 1970 shows Kagan’s presumption of Congress’s belief in its own incompetence to be mistaken. In response to concerns about power stations causing acid rain, in 1990, Congress passed the Clean Air Act Amendments by large majorities in the House of Representatives (401-21) and the Senate (89-11). Title IV of the legislation set nationwide limits on sulfur dioxide emissions and created a market for tradable emission permits, as Congress had determined that cap-and-trade would be the most efficient way for power plants to meet these targets. There was no question in 1990 of the EPA using its supposed Section 111 (d) authority that Congress had passed twenty years earlier. When Congress was presented with a new environmental problem and was minded to act, it made a new law and instructed the EPA to execute it.

Kagan argues that under normal principles of statutory construction, the Court should have ignored Congress’s rejection of cap-and-trade schemes for greenhouse gas emissions. As she points out, Congress also failed to enact bills barring the EPA from implementing the Clean Power Plan. Whatever the legal arguments, that there were multiple attempts to pass climate legislation that failed is of great political significance. In November 2010, after Democrats’ shellacking in the 2010 midterm elections, the prospects of Congress passing any climate legislation disappeared. With the legislative route blocked, President Obama declared, “I’m going to be looking for other means to address this problem.” That’s how Section 111 (d) came to serve as the linchpin of the administrative state’s attempted nullification of the 2010 election loss.

The administrative state’s threat to democratic accountability, which does not feature in Kagan’s dissent, is the theme of Gorsuch’s concurrence. “The framers believed that a republic – a thing of the people – would be more likely to enact just laws than a regime administered by a ruling class of largely unaccountable ‘ministers,’” Gorsuch argues. He cites his about-to-retire colleague Stephen Breyer — who signed Kagan’s dissent — on the dangers of the legislative branch divesting its power to the executive branch and the risk of legislation becoming nothing more than the will of the current president or, worse, the will of unelected officials barely responsive to him.

Where Kagan praises the growth of the administrative state, Gorsuch condemns Woodrow Wilson and his argument that popular sovereignty embarrasses the nation by juxtaposing it with Wilson’s justification for the South’s racism and his denunciation of immigrants who have “neither skill nor energy nor any initiative of quick intelligence.”

These are not legal arguments. The disagreements between Kagan and Gorsuch, and between the court’s current minority and majority, reflect differences in political philosophy and interpretations of America’s history. As such, they can’t be resolved by appeals to legal doctrine alone. By quashing the already extinct Clean Power Plan, the Supreme Court chalked up a win for democracy over the administrative state. That is something to celebrate this weekend.

Rupert Darwall is a senior fellow at the RealClear Foundation and author of Green Tyranny