San Francisco mayor London Breed held a press conference on October 5 concerning her city’s most deadly problem: the open air drug market in the Tenderloin neighborhood. The speakers included the police chief and two newly appointed allies of the mayor: the district attorney, Brooke Jenkins, and the supervisor for the district adjacent to the Tenderloin, Matt Dorsey. The message from each of them was clear: the police and the district attorney would no longer ignore open drug dealing and public drug use, which has become endemic in downtown San Francisco. “Let’s be clear: selling drugs is not legal,” the mayor said. “Using drugs out in the open is completely unacceptable.”

The city could be forgiven for needing the reminder. The Tenderloin has been a haven for drug dealing and drug addiction for generations, but over the last few years it has exploded. Sporting hoodies and backpacks and armed with guns and knives, drug dealers from Honduras, supplied by Mexico’s Sinaloa drug cartel, peddle methamphetamines, fentanyl, heroin and prescription drugs with little more furtiveness than an unlicensed food cart selling hot dogs. Users smoke meth and shoot up smack on the sidewalk and pass out on the pavement. Others scream and rage in drug-induced psychotic states. Only recently have the police begun to do anything about it. For years, officers would just stand there watching, like human totems to the city’s lawlessness.

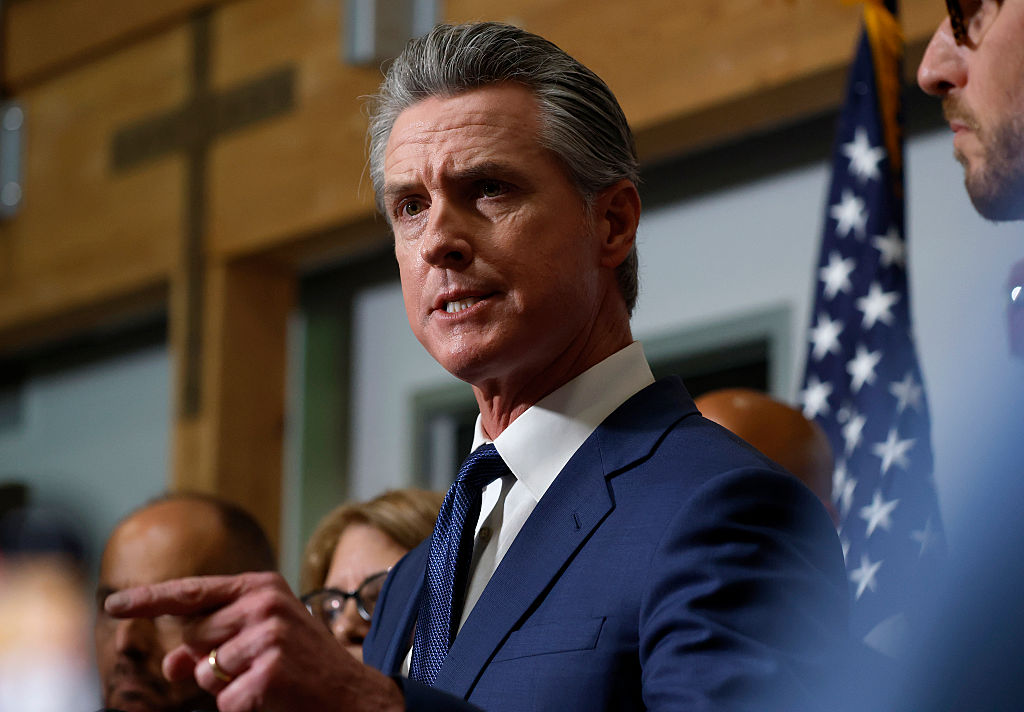

Next week, San Francisco residents will vote on whether the city’s experiment in effectively decriminalizing crime has failed. The answer may seem self-evident to most, but standing in the way of change is a powerful faction of the city’s notorious political machine, which is ideologically committed to taking the experiment even further. To them, Brooke Jenkins’ resolve to enforce the city’s laws amounts to nothing less than a return to Richard Nixon’s “War on Drugs.” Voters, however, don’t seem to agree.

Once contained to the Tenderloin, the mayhem on San Francisco’s downtown streets has spilled over to the south side of Market Street, into Dorsey’s district, known as SoMa. Users and dealers clog the sidewalks in front of luxury towers for tech workers that have emptied out as a result of the tech industry’s slow exodus from the city since the start of the pandemic.

“It was a war zone,” said Reese Isbell, a resident of SoMa whose block had been taken over by drug dealers before Brooke Jenkins was DA. He and other tenants in his building started a Slack group to discuss the problem. “We were trying to organize and keep each other posted on what we were going through,” he said. “You know: ‘There’s a guy with a machete out there — be careful.’ ‘Be careful, they’re shooting at each other today.’”

Meanwhile, petty crime has inundated the city, creeping into affluent areas where it had once been all but unknown.

Isbell wasn’t alone. “Communities I work with and represent are organizing Neighborhood Watch, talking and communicating with each other, doing for ourselves what the city can’t do for us,” said Christian Martin, Executive Director of the SoMa West Community Benefit District. Martin represents 107 blocks of the neighborhood. He estimates that 40 percent of them are organizing some sort of self-protection committee.

Voters in San Francisco are fuming over these chaotic conditions. According to a recent poll by the San Francisco Standard, out of multiple government entities — the Mayor, the Board of Supervisors, the police, the public schools, and the District Attorney — DA Jenkins, the only one of the bunch who can’t be associated with the status quo, is alone in being more popular than she is unpopular. Two-thirds of voters disapprove of the Mayor, while three-quarters disapprove of the Board of Supervisors. (In San Francisco, which is both a city and a county, the Board of Supervisors is the equivalent of a City Council.) Last summer, San Franciscans voted decisively to recall the famously lenient District Attorney Chesa Boudin, just months after recalling three far left school board members.

But that hasn’t stopped San Francisco’s progressive politicians from sticking with the same approach to the addiction crisis that has resulted in the present situation. “Despite the recalls’ overwhelming success, the progressive Supervisors have not changed their tactics,” said Kanishka Cheng, Founder of Together SF Action, a good government group. “They’ve doubled down on the status quo. They think the recalls were a flash in the pan — their spin is that Republican billionaires bought the election, that it wasn’t about their own mistakes and failures.”

The progressives seem to regard the new DA as something like an existential threat to their decriminalization agenda. Two days after the press briefing, Mano Raju, San Francisco’s Public Defender, attacked the Mayor’s announcement, tweeting, “A new War on Drugs has been launched in SF.” He announced his own counter-press conference of sorts, this one via Zoom.

Supervisor Dorsey, who runs for his appointed seat in next week’s election, responded to Raju’s tweet the next day. “Last year, @ManoRajuPD’s drug-dealing clients had 25.5 kilos of fentanyl seized in arrests — enough to wipe out the Bay Area’s entire population — and it killed 477 San Franciscans in 2021,” Dorsey tweeted. “The number of @ManoRajuPD’s clients prosecuted for fentanyl dealing that year? ZERO.”

The “ZERO” was a reference to Boudin’s record. In any other city, criticizing a public defender by invoking the record of a former district attorney would make no sense; the two are ostensibly on opposite sides. But over the two-and-a-half years of his prematurely shortened term, Boudin, a career criminal defense attorney, had made the DA’s office into a veritable extension of the office of the San Francisco Public Defender. Instead of using his power to help shut down the open air drug market, as a traditional DA would be expected to, Boudin devised new ways to shield dealers from the legal consequences of their crimes. He claimed that many of the Tenderloin drug dealers his office was responsible for prosecuting were victims of human trafficking, a claim that former assistant district attorney Tom Ostly and current assistant district attorney Nancy Tung said was without evidence. On that basis, he routinely reduced felony drug sales charges to misdemeanors in order to avoid triggering a California state law that mandates the deportation of any non-citizen convicted of certain crimes. He also used diversion programs, which are generally meant for drug users, not sellers, to steer dealers away from jail time, if he didn’t dismiss the charges outright.

Along with the Department of Public Health, the former DA and the Public Defender formed something of a political bloc within the city government that steered San Francisco toward a program of de facto decriminalization of drug use, drug sales, organized shoplifting, larceny, and public camping. (Raju declined a request for an interview.) In response to the escalating crisis in the Tenderloin, instead of ratcheting up enforcement by police, Mayor Breed and the Department of Public Health opened up an illegal, city-supervised drug consumption site on Market Street. The Tenderloin Linkage Center failed to bring outdoor users inside, as advertised. Instead it turned the already seedy adjacent United Nations Plaza into a giant drug bazaar. Users would buy from dealers just on the other side of the center’s chain link fence, and then either smoke right there on the plaza, or a few feet away in the Linkage Center’s makeshift courtyard. The experiment was such a failure that the Mayor is shutting the center down, but that hasn’t stopped the Department of Public Health from planning to open up new supervised consumption sites in the future.

The SFPD responded to this new political climate by effectively going on an enforcement hiatus. “They didn’t see the point of arresting people because they’d be arrested four or five times and just be back out on the street,” said Randy Shaw, executive director of the Tenderloin Housing Clinic, which provides housing for homeless San Franciscans.

The city’s hands-off approach, combined with the lockdowns and social isolation brought by the pandemic, led to a surge in overdose deaths; during the two full calendar years of Boudin’s tenure, fatal overdoses were double those of the prior two.

As the pandemic emptied downtown of its office employees, who were now working from home, the open air drug market, now centered on UN Plaza, grew bigger and more brazen. The Mid-Market and SoMa areas, once bustling with commuters, became no-go zones for most San Franciscans who could avoid them. For those who couldn’t, the steadily worsening blight was like a billboard, advertising to voters what failed political leadership looked like. But you didn’t even have to go downtown to see the social decay. Business owners in the largely residential Castro district grew so frustrated with the ensuing lawlessness that last summer they declared a tax strike until something is done about crime and vagrancy in their neighborhood.

In June, Boudin lost the recall election by a ten point margin, and Mayor Breed appointed Brooke Jenkins as his interim replacement. Jenkins had once worked for Boudin, but had turned on him and become a face of the recall campaign. Since being appointed, she has been unambiguous about her intention to arrest and prosecute drug dealers and to push users into treatment. In September, she announced that she was considering charging fentanyl dealers whose sales could be connected to fatal overdoses with murder. Sixty-nine percent of San Francisco voters support the new policy, according to an SF Standard poll.

So does Supervisor Dorsey, a gay, HIV-positive recovering addict whose last job was the press spokesman for the San Francisco Police Department. At the beginning of October, Dorsey, who, like Jenkins, is an interim appointee of the mayor, organized a volunteer clean-up of the drug-infested intersection of Eighth and Mission. He brought a stack of photocopies of an article in the San Francisco Chronicle with the headline, “SF DA Brooke Jenkins says she’ll consider murder charges for fentanyl dealers.” Volunteers taped the article to the walls, so the drug dealers could read it. Local reporter Erica Sandberg and Gina McDonald, a former addict whose daughter is in recovery, watched three lookouts for the dealers reading it, before scattering when two police officers on foot patrol came into view.

Aligned against Jenkins is the city’s progressive faction, starting with the Public Defender. At the counter-press conference that he had announced in his tweet, Raju called Jenkins’s proposals, including murder charges for fentanyl dealers, “more of the same failed, regressive approaches,” which he and most of the other participants on the Zoom call equated to the “War on Drugs.” The press conference’s speakers laid out an alternative strategy, which was basically the same model that has prevailed in recent years. Norma Palacios from the Drug Policy Alliance attributed the conditions on San Francisco’s streets to the city’s “massive disinvestment in the needs of its residents” and called for “substantial investments” in permanent supportive housing for the homeless. (Palacios did not respond to an interview request.)

This language doesn’t match the numbers. San Francisco’s homelessness budget in 2021-2022 was $1.1 billion. That’s equivalent to the city’s entire public school budget for 2022-2023. The city’s current homelessness budget comes out to about $140,000 per unsheltered homeless resident — seven times the amount spent on each San Francisco public school student. Most of that money goes to what Palacios claimed was so grossly underfunded: permanent supportive housing.

Palacios went on to lambast the city for “criminalizing drug sellers,” claiming that drug dealers in San Francisco are often just trying to sustain their own addictions, or that it’s their “only source of available income.” She described the dealers as low-level operators who are victims of racial profiling by the police.

This depiction is at odds with the accounts of people who have directly interacted with the Tenderloin drug trade. To be sure, there are addicts who sell small amounts of drugs on the side to sustain their habits. But the drug dealers who drive most of the traffic in the Tenderloin are supplied daily by the Sinaloa drug cartel. “They have rules,” said Tom Wolf, a former Tenderloin addict who now advocates for shutting down the open-air drug market. “None are allowed to use their own product. If they get addicted they get kicked out of the ring.”

It’s a highly organized business, in which dealers work in shifts and even have lunch delivered to them by their colleagues. According to Tom Ostly, the former assistant district attorney in the Tenderloin, street-level dealers in San Francisco clear $1,000 a day, easily. Recently the police arrested a dealer in the Tenderloin who was carrying nearly eight pounds of fentanyl, enough to kill 1.5 million people.

Nevertheless, the progressives regard drug enforcement, not the drug trade, as the real threat to San Francisco. “The Drug War actually does more harm than drug use,” said Maurice Byrd, a speaker at the press conference.

San Francisco voters will choose between these two starkly polarized factions. The politics of the addiction crisis have made the outcomes of local races less predictable. In the Sunset District, Gordon Mar, a progressive who opposed the school board recall and appeared in ads against Chesa Boudin’s ouster, is running against Joel Engardio, who heads a public safety group called StopCrimeSF that engaged in a prolonged fight with the former DA over a public records request. Mar is Chinese American in a heavily Chinese district, but it was Chinese San Franciscans who pushed hardest to fire the school board members, one of whom had tweeted out racist comments about Asian Americans, and to recall Boudin, who was perceived as indifferent to the victims of anti-Asian street violence. Engardio, who is white, has a decent chance of beating Mar among Asian voters, among whom Brooke Jenkins is twice as popular as among the electorate at large.

Dorsey and Jenkins are both running for the seats they were appointed to. Although they’re the picks of the Mayor, that doesn’t make them the favorites of the city’s political establishment. Dorsey is running against several challengers, the most serious of whom is Honey Mahogany, an Ethiopian-American trans woman who was once a contestant on RuPaul’s Drag Race. The San Francisco Democratic County Central Committee, the official Democratic Party apparatus of the city, endorsed Mahogany over Dorsey, as did the San Francisco Labor Council, a powerhouse in city elections. The Democratic Party also endorsed Jenkins’s challenger, John Hamasaki, a radically anti-police lawyer, as did the politically powerful Service Employees International Union.

It’s entirely possible, however, that the local Democratic Party is once again out of step with the Democratic voters it represents, just as it was when it opposed the recall of Chesa Boudin. The elected leaders of the SFDCCC are mostly political operatives: labor leaders, current and former elected officials, political staffers; Raju, for instance, is a committee member, and Mahogany is its Chair. It acts as an organ of the progressive faction of the San Francisco political machine.

“Their power is consolidated into one perspective that doesn’t represent mainstream Democrats,” said Cheng. Shaw believes the SFDCCC’s opposition to the highly popular new DA might make the party’s endorsements so irrelevant that its support for Mahogany might actually count against her.

Isbell, who has been active in grassroots San Francisco politics for decades, has never seen political insiders so out of step with the public. “There’s this endorsement world and internal City Hall world, and then there’s the real world that recalled Chesa,” he said.

In that real world, the changes Jenkins has brought have been visible to voters. “She went and talked to the officers in the precincts and said, ‘I’m with you,’” said Shaw. “Now arrests are being made.” Isbell’s block is finally rid of drug dealers, apart from a few stragglers. As voters watch the blight downtown recede, one block at a time, will they be willing to put that change at risk by voting against the DA and her allies?

Shaw doubts it. “This election,” he said, “will be a real wake-up call for San Francisco.”