The Taliban Cultural Commission sounds a contradiction in terms but for all foreign journalists it’s the first stop in the new Afghanistan. There, in a dusty office on the first floor of the old Ministry of Information, I was handed a letter which allowed me to go anywhere in the country, except Kabul airport or military installations. In a neighboring office I met Anamullah Samangani, a Taliban commander from the northern province of Samangan. He’s an Uzbek, resplendent in crisp white shalwar kameez, black waistcoat and black and white silk turban. He told me he has read one of my books. ‘Do you feel safe in Kabul, have you had any difficulties?’ he asked. He assured me that the new Taliban just want to be friends. ‘We have learnt from experience and now we want to connect to the world and interact with them in a good way, especially western countries.’

It’s hard for me to get my head around. Not long ago they would have viewed foreign journalists as potential targets for kidnapping. Several fighters I chatted to on the street exclaimed ‘Why are you back?’ when they found out I’m British, but then they asked for selfies with me and sent me WhatsApps with flower emojis. It’s all part of a Taliban charm offensive, which started a couple of months back when they created a WhatsApp group for foreign journalists. The billboard at Kabul airport, which once bore the president’s picture, now proclaims: ‘The Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan seeks peaceful and positive relations with the World.’ But the I ♥ Kabul sculpture on the grass in front has tellingly lost its heart.

Hard as it is to see Kabul like this, I was relieved finally to be here. I was deep in the Amazon, on assignment in a remote village, when Kabul fell. The village had solar power and a daily WiFi hour, which was just enough to get a stream of texts asking if I was safe, as well as messages from Afghan friends begging for help to escape. I couldn’t believe that after 33 years of reporting from Afghanistan I had missed the main event. I couldn’t have been further away. It took a three-hour canoe, two-hour drive, eight-hour boat and three flights just to get out of Brazil. Then on to Europe; in Pakistan, a quick shop to buy a black niqab at the Dignity Store, and finally a 10-hour journey overland by road. Six PCR tests in two weeks — traveling these days is a complicated business.

At my hotel guards held out a mirror on a stick to check under my chassis for bombs. The BBC’s Lyse Doucet, Lindsey Hilsum from Channel 4 and I were told by embarrassed receptionists that we must cover our heads even inside. That evening there was an enormous barrage of gunfire and I rushed out of my room thinking that we are under attack. ‘The Taliban are celebrating,’ shrugged the front desk manager. Out on the streets the Taliban were riding around in Nato-supplied police jeeps, their white flags flying. One wore a US Army cap and carried an American M16. ‘Got them in Bagram,’ he smiled. ‘And these!’ He waved his feet, which were clad in new desert boots.

I have been here nearly a week and I have seen small protests everyday from women holding up placards demanding their rights. Shots are fired to disperse them but still they come out. Women, say the Taliban, can’t go to work at the moment ‘for their own security’. That’s what they said when they took power last time in 1996. Five years later apparently it was still not secure.

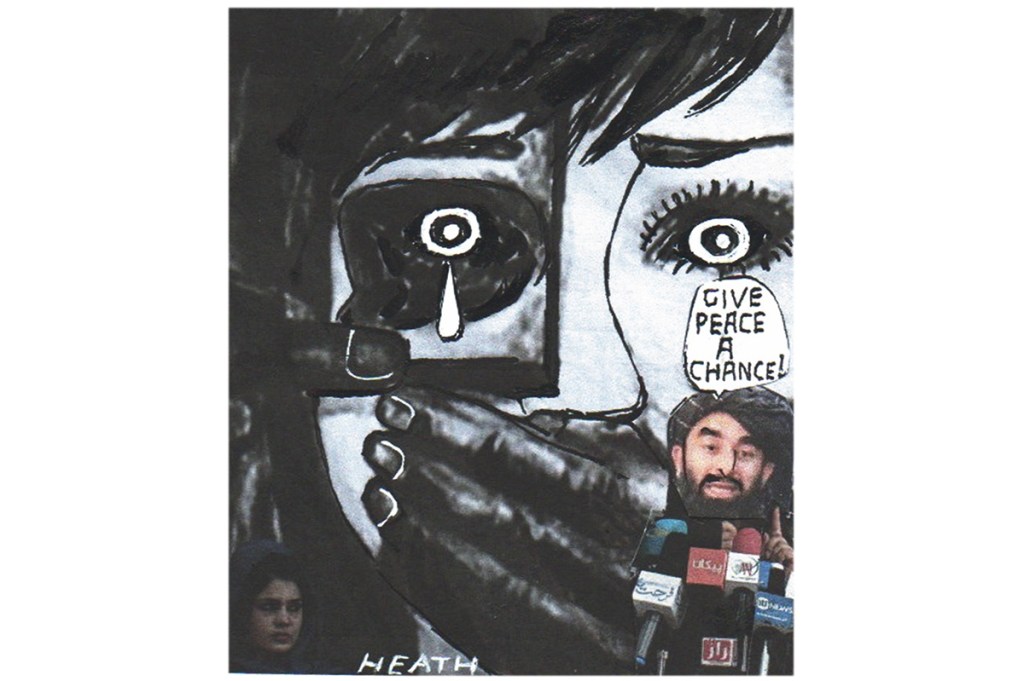

A Taliban press conference was an invitation I couldn’t turn down. It was held in the government media center built by the Americans at great expense. Taliban spokesman Zabiullah Mujahid walked down the stairs, checked himself and then sat in front of rows of cameras. As a woman I was made to sit at the side of the room. I waved my hands but he had a list of people who could ask questions. He answered politely but selectively. There was only one question I really wanted answered and it will take months to know. Have the Taliban changed or is it just a facade to get foreign aid?

Many of my friends have fled or are in hiding. Only one was brave enough to meet up, a rapper. ‘I am OK — physically,’ she says. ‘Overnight we saw our lives turn black.’ Her best friend broke her acoustic guitar in half on the day the Taliban took control of Kabul. Every night since, the pair have sat on the roof looking at the stars and crying. It’s hard to imagine how once we drove around the city together in a taxi while she rapped. What was the point of the past 20 years? We gave people like my rapper friend the chance to dream and then we snatched it away. Would it have been better if we had never come?

Christina Lamb is chief foreign correspondent for the Sunday Times of London and author of Farewell Kabul. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2021 World edition.