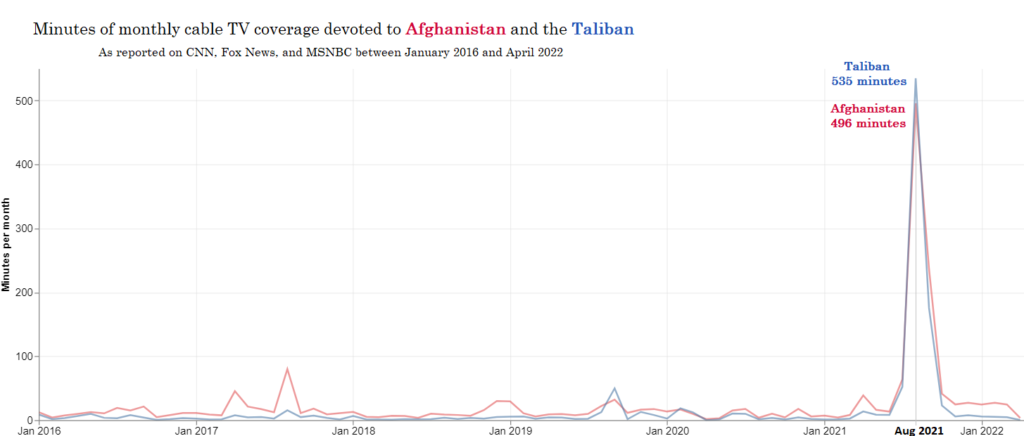

For Americans, neglecting Afghanistan has long been the norm. Almost from its inception, it was the forgotten war, fought “over there so we do not have to face them” here, as President George W. Bush once put it. It was a campaign to crush the Taliban only to abruptly become a democratic nation building project and then just as quickly be sidelined for the “real war” in Iraq. Even as far back as 2009, when the United States still had 62,000 troops in the country, David Folkenflik, NPR’s media correspondent, was asking, “Hey, Media: Where’s the Afghanistan Coverage?”

This all appeared to change last August — at least for a time. As the United States began withdrawing from Afghanistan in earnest, the media reacquainted the American public with the twenty-year-old war using the kind of “winners and losers” punditry that elevates soundbites over nuance.

Soon, a hysterical press corps was heaping condemnation on President Joe Biden for exiting a war that the American public had wanted out of for some time. The withdrawal became about “Biden’s Saigon” and American weakness, not actual accountability or how the Afghanistan Papers had already revealed the war to be a farce.

Then, just as quickly as it started, the coverage vanished. While this was somewhat expected following the US departure, the media’s readiness to wash its hands of the whole affair after weeks of emotive appeals to stay the course was particularly jarring.

Take the plight of Afghan women, for example. The Taliban’s reconquest rightly raised concerns that women would face renewed repression under their regime. However, as Cheryl Benard and others have observed, the notion that the United States had “abandoned” Afghan women was duplicitous, for the West’s conception of an “Afghan women” was incomplete. With reporters sticking mostly to the cities — which were safer than the war-torn countryside — the media presented a constructed version of what an Afghan woman truly was: an elite human rights lawyer or an educator who had embraced Western modernity.

Left ignored was the poor, traditionally conservative Afghan who had faced unimaginable violence from American drones and the Afghan National Army. “This scale of suffering was unknown in a bustling metropolis like Kabul,” Anand Gopal wrote for the New Yorker, “[b]ut in countryside enclaves like Sangin the ceaseless killings of civilians led many Afghans to gravitate toward the Taliban.”

Of course, that America’s war in Afghanistan killed more than 176,000 people (including 46,000 civilians) and made Afghans poorer hardly penetrated the media bubble, which burst as the last US combat boot left the country. Yet even so, the war against the Afghans did not end; it merely evolved. In fact, even as the US military was retreating from a capital city that a bewildered Taliban had effortlessly conquered, the Biden administration was holstering its military weapon and drawing its economic one.

The salvo began in mid-August, when the White House recoiled in response to the Taliban takeover by freezing $9.4 billion of the Afghan central bank’s international reserves — most of which was being held at the US Federal Reserve Bank of New York — imposing sanctions, and blocking the International Monetary Fund and World Bank from disbursing billions in emergency support. For an Afghan economy that was already struggling with a drought, the coronavirus pandemic, and the loss of other foreign aid and investment, this was a death knell.

American sanctions and asset freezes sent the Afghan economy into free fall. Banks closed, salaries went unpaid, and inflation and unemployment soared just in time for winter, raising fears of imminent famine. In September, the United Nations warned that one million children were at immediate risk of starvation. By December, that number had exploded: 23 million Afghans (55 percent of the population), including 14 million children, were facing “extreme levels of hunger.” Parents began selling off their girls to feed their emaciated families. So much for caring about Afghan women.

For now, the Biden administration has averted widespread famine in Afghanistan by issuing sanctions waivers and providing more than $800 million in humanitarian relief. However, foreign aid — which sustains a country’s dependence on external assistance and inefficiently wastes funds paying for NGO overhead — is no substitute for a functioning Afghan economy.

Moreover, Biden’s February decision to redistribute $7 billion of Afghanistan’s frozen assets between a humanitarian trust fund and payouts to relatives of victims of 9/11 is particularly cruel. Considering that this money does not belong to the Taliban, but the Afghan people; that Afghans are not to blame for the Taliban’s rule; and that Afghans are not responsible for 9/11 — i.e., none of the hijackers were Afghans — the Biden administration’s actions are more theft than policymaking.

Handing out $3.5 billion in stolen Afghan money to the families of 9/11 victims is certain to see that money tied up in court; holding out the other $3.5 billion over the Afghan people’s heads in a gambit to forcibly liberalize the Taliban is absurd. Both moves suggest that an affronted America wants to punish the Afghans for its loss against the Taliban.

The outcome will be that more Afghans suffer, and that their country’s problems become the world’s. This is the major story the media refuses to cover.

Adam Lammon is executive editor of the National Interest and a fellow in Middle East Studies at the Center for the National Interest.