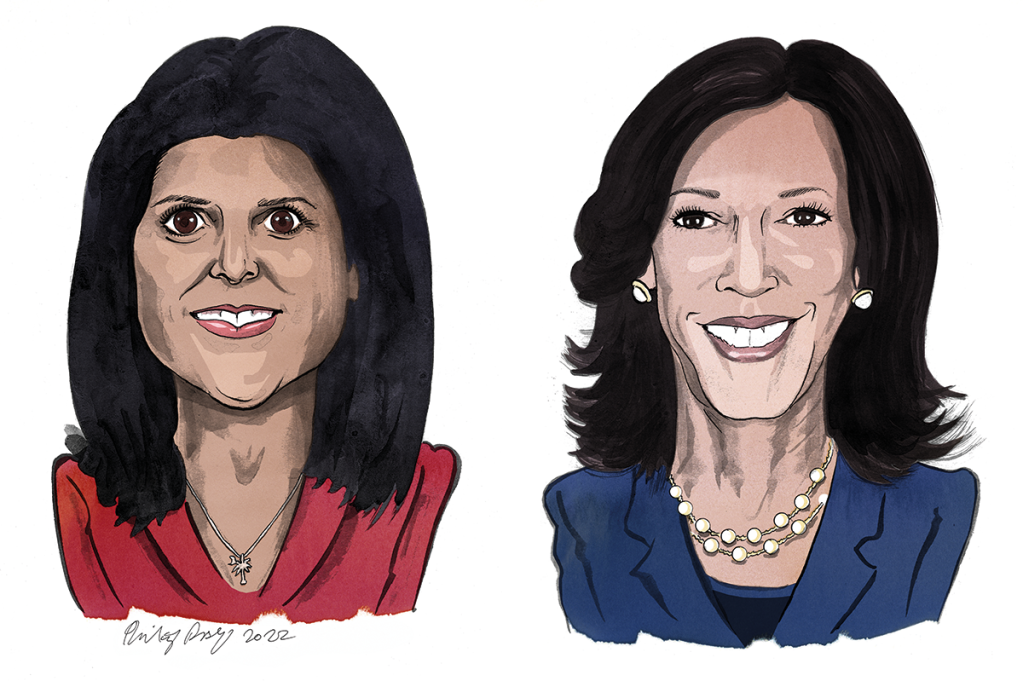

You don’t have to be obsessed with racial calculations to consider the possibility that the next presidential election in the United States could be fought between two American-born women with roots in India: Nikki Haley in the red corner and Kamala Harris in the blue, the Republican Sikh and the Democratic Tamil Brahmin (on the side of the sainted mother who raised her), duking it out for leadership of what’s left of the Free World.

The probability of this happening dwindles by the day, of course, as Vice President Harris makes it ever clearer that she’s too lightweight for the White House, and that nominating her for president would be electoral suicide for the Democrats. (Besides, hubris may drive Joe Biden to run again.) As for Ms. Haley, any run by her — as, indeed, by any other Republican — is hostage to the whims of Donald Trump. Other Republicans might challenge Mr. Trump for the nomination, but Ms. Haley seems unlikely to do so. She will, like a good Sikh warrior, bide her time till the citadel he seeks to capture is more vulnerable. But the plausibility of a Harris v. Haley matchup for 2024 nonetheless says something remarkable about the strides that ethnic Indians have made in America. While far from a Takeover of America, as some of the more puffed-up Indians might boast, it’s considerably better than a Jolly Good Show.

Indians may be the second-largest immigrant group in the US after Mexicans. But their numbers — just over four million – put them at a paltry 1.2 percent of the American population. Their achievements, however, show a far greater heft. Some commentators have described Indian Americans as the New Jews. This is lazy but, as with many stereotypes, it isn’t entirely unhelpful.

The statistic of which self-congratulatory Indian Americans — of whom there’s no shortage — are most proud is that their median household income is the highest of any ethnic group in America. At $126,705, it is almost twice that of white Americans, and nearly three times that of African Americans. (It is also four times greater than the group at the bottom of the pile, Somali Americans.)

There are other stats suggesting “disproportionate” success. (I use the quote marks because I’ve always been puzzled by those who expect an ethnic group’s achievement to mirror its demographic proportions.) Every seventh doctor in America is Indian (including the surgeon general), which may explain the number of times a bartender has said to me on my travels through Middle America, “So what’ll it be, Doc?” (That’s ethnic stereotyping I can live with.)

Forty-five CEOs of US companies are Indian. The latest, Parag Agrawal of Twitter, joins an astonishing list of Indians at the helm of tech companies, including Alphabet, Inc. and Google, Microsoft and Adobe. Ninety of the founders of the top 500 “unicorns” (privately held startups valued at greater than $1 billion) were born in India.

The Indian domination of America’s hotel and motel sector is well-chronicled, with more than half of the country’s motels in Indian hands. The Indian presence on Wall Street and at American universities (particularly on STEM faculties and at business schools) is also eye-catchingly high. Less well known is the increasing infiltration of American journalism by ethnic Indians, which has had an inevitable impact — mostly positive — on how seriously India is taken by American media.

When I came to live in the US in 1997, as the New York bureau chief of the London Times, I was feted as a rarity by the South Asian Journalists’ Association (SAJA), a painfully earnest networking group set up to boost the American media presence of journalists with roots in the Indian subcontinent. I was an Indian journalist who’d “made it” in the West. If I arrived today, my presence would be greeted with a bored shrug. From editors to editorial boards to pundits on TV and reporters on every conceivable beat, American journalism is awash with desis (as ethnic Indians sometimes refer to themselves). When I was invited to speak at a SAJA meeting a few years ago, I took the opportunity to suggest the disbanding of that ethnic guild. “Do we really need more Indian journalists in America?” I asked.

I have not been invited back since.

After the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 removed the legal bar on immigration to the US by nonwhites, Indians started to come to America in numbers. A useful chart in Sanjoy Chakravorty, Devesh Kapur, and Nirvikar Singh’s The Other One Percent — the single best book on Indians in America — shows that a mere 3,000 Indians were naturalized between 1961 and 1970; in the same decade, 873,000 people of European origin were. Between 2001 and 2010, the number of Indians naturalizing had reached nearly half a million.

The impact of Indian immigration to the US is exceptional, especially if you add the strides made by Indians in politics and the public service to the ledger of their “conquest” of America. We’ve had Indian-American governors of Louisiana and South Carolina, as well as a half-Indian vice-president (who’s more of a heroine in her mother’s birthplace, Tamil Nadu, than in her father’s Jamaica). The Biden administration is awash with thrusting, technocratic Indians at various levels; and — a dubious distinction — one of the most radical members of the House of Representatives is Pramila Jayapal, from Washington’s 7th Congressional District. The congressman for Silicon Valley is —perhaps inevitably — Indian. Indians are present in state legislatures and as mayors, including the mayors of Anaheim and Irvine in California, and Hoboken in New Jersey.

In the last four decades of the twentieth century, Indian immigrants were largely self-selecting and ambitious strivers. They benefited from what The Other One Percent calls “triple selection”: (1) Higher-caste Indians with (2) access to the best higher education in India feeding into (3) an America that hungered for their skills. The political timing was perfect: barriers to immigration were lowered in an era when India, still largely socialist in its economic preferences, had no capacity to absorb high-skilled graduates, many of them alumni of the Indian Institutes of Technology. These had been set up by the socialist prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru in 1951 to promote a “scientific temper,” but they ended up as feeder schools for the American economy. Some 50,000 IIT alumni are settled in the US. India’s “STEMmigrants” also include the thousands who have come to the US under H-1B visas, tied to employment in the tech sector but with prospects, always, of naturalization.

The US wasn’t squeamish about brain-draining India. Thousands of graduates, many in the top 1 percent of their classes, chose America. They became the first large-scale cohort of ethnic immigrants to the US that didn’t have to work its way up the ladder to middle-class and professional status. They had college-educated parents and, often, grandparents. They spoke English and were skilled already at navigating a plural or “multicultural” landscape. They were already versed in the ways of democracy and found in America a society that was inclined to embrace foreigners like no other society in human history — a society predicated, in fact, on immigration.

The Sixties and Seventies were still a time when immigrants were expected to assimilate, so a Laxminarayanan learned quickly to call himself “Lax” and a Balasubramanian became “Bill.”

This self-selected group of Indians had other advantages that helped them bed in. They came voluntarily, with no history of pogroms or poverty behind them. They were fleeing economic sterility, so took to America’s meritocracy with delight and hunger, since there was no opportunity for them in India’s overregulated crony capitalism. Sundar Pichai (CEO, Alphabet, Inc.) and Satya Nadella (CEO, Microsoft) would never have become helmsmen of an Indian company.

Slotting straight into professions in America, they had none of the angularity — for want of a better word — that characterized other ethnic groups in their struggle up the American ladder. Americans found Indians more gentle and less chippy to deal with than other immigrant groups. Of course, Indians faced racism, but they handled it differently, perhaps stoically. In any case, as a young second-generation techie with roots in India told me, “There’s an earnest belief in the American Dream that is likely stronger than in most other immigrant communities.”

Their passion for America is also bolstered by their newfound existence in a secure legal environment where few people cheat, where property rights are respected and where there is none of the humdrum but soul-sapping accommodation that needs to be made with venality at every level. They can focus their energies exclusively on education, making money and raising a stable family — which, studies show, Indians do better than anyone else in America: 94 percent of first-generation Indian immigrants with children are married. The group also has, at 2 percent, the lowest rate for children born out of wedlock.

Success in America, a national columnist who is white tells me, has bred high levels of self-confidence among Indians, bolstered no doubt by the awareness that America does them no special racial favors. This results in a certain hardy self-esteem. “When an Indian has been here ten years,” the columnist says, “he goes on Morning Joe to explain our history to us — to me. The Poles who immigrated here didn’t do that. Even the Irish. It took everyone else time.”

Certainly, it has been a long time since it’s been an advantage to apply to an Ivy League school as an Indian. And as an unfortunate recent episode demonstrates, being Indian doesn’t really confer a benefit with the racial actuaries who conduct politics in America.

Reacting to the likely nomination of a black woman to the US Supreme Court — a campaign promise made by Joe Biden — a libertarian professor at Georgetown tweeted that there was a much better choice Biden could make than any of the “lesser” black women being touted as candidates. He meant they were lesser in terms of their ability and jurisprudence, of course, and expressed chagrin that his choice would not be considered because he “doesn’t fit the latest intersectionality hierarchy.” The professor has been put on administrative leave pending an investigation into alleged racism.

Was the judge he proposed a white Anglo-Saxon? Was he Jewish? Italian? No. He was Sri Srinivasan, chief judge of the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, and he was born in India.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2022 World edition.