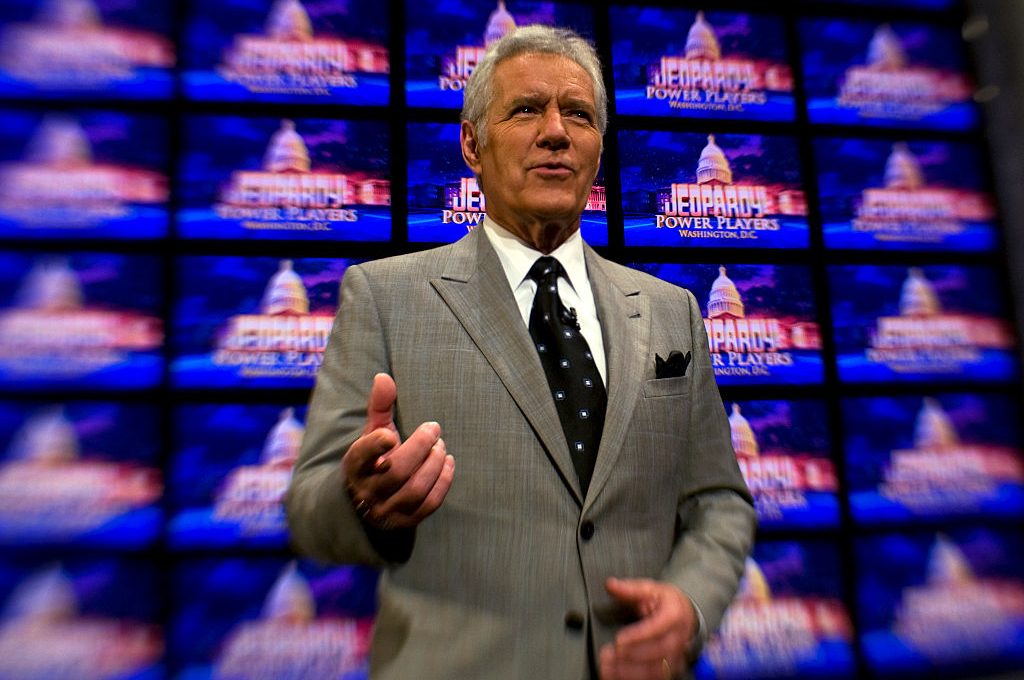

Just before the start of the fall semester, New York University fired the distinguished professor in organic chemistry Maitland Jones Jr. NYU’s dean for Science Gregory Gabadadze informed Jones in a terse letter that his work “did not rise to the standards we require from our teaching faculty.”

Jones is a legend in his field who literally wrote his subject’s 1,300-page textbook Organic Chemistry. He had been teaching at NYU on a renewable one-year contract since his retirement, in 2007, from a forty-three-year career at Princeton University. During his time at NYU, Jones won teaching awards. In 2017, he was named one of NYU’s “coolest” professors, a distinction he shared with only seven of his nearly 10,000 colleagues.

Jones’s offense? His class was too hard. Earlier this year, eighty-two of Jones’s 350 students signed a petition denouncing the difficulty of his organic chemistry course and bemoaning the high failure rates on his examinations.

Although more than 75 percent of Jones’s students did not sign the petition, and although the petition itself did not demand his dismissal, NYU scrambled to placate the disgruntled minority. Every NYU undergrad is, after all, a precious little bundle worth over $300,000 in tuition payments — in addition to potential alumni donations down the road. The students are also far more skilled in social media kvetching than any fortysomething Snopes who works in NYU’s recruitment operations. A bad class, a martinet professor — these things can easily become that afternoon’s widely shared Instagram post or TikTok reel.

NYU’s chemistry department offered to review the exams of Jones’s aggrieved students and, unusually, to allow students to withdraw from his class retroactively. The goal, its director of undergraduate studies explained to Jones shortly before he was fired, was to “extend a gentle but firm hand to the students and those who pay the tuition bills,” presumably their parents, though such reactionary terminology may no longer be acceptable at NYU.

“In short he was hired to teach, and wasn’t successful,” barked an NYU bureaucrat when challenged. This ignored that Jones had risen to the top of his profession over decades of employment at a much higher-ranked university, had his NYU contract renewed annually for fifteen years without issue, and won teaching awards. The idea that NYU students could not be successful is apparently unthinkable.

Organic chemistry is a vitally important course for determining medical school admissions. A good grade in it can go a long way. A bad grade can blight an aspiring doctor’s record so badly as to destroy any chance of admission. This likely accounts for why so many NYU undergrads lamented their poor grades in Jones’s class. But firing Jones goes so far beyond parody as to reveal something much uglier about academia.

In short, for all his accomplishments, Dr. Jones is dispensable, as are all of his colleagues at all American universities, regardless of their field. Every university administration knows full well that for every available teaching position, there are scores, if not hundreds, of acceptably credentialed people willing to do the same job. Savvier administrators have long realized that full-time professors, especially those protected by tenure, are also dispensable, and that their jobs can be done by so-called “contingent” faculty. That broad category includes people like Jones, who teach on temporary contracts, as well as adjunct instructors, who might be engaged for one or two courses on a semester basis, or graduate students, who can hold teaching responsibilities as a condition of receiving financial support or as part of their training.

Whether a class is taught by the preeminent scholar in a field, a first-year hire just out of graduate school, or a doctoral candidate who barely speaks English is immaterial. Students will pay the same tuition regardless. And since what most students really want is the piece of paper at the end, barely anyone ever complains. The only serious objections are limited to obscure industry publications in which a handful of insightful but powerless academic professionals whine about “adjunctification” diminishing career opportunities. Like so many betrayed Cassandras, they have idly looked on while the proportion of contingent faculty increased from 30 percent in 1982 to over 75 percent today.

All the administrators have to do is make sure the students pay, attract new students to pay more next year, and preserve their monopoly on issuing educational credentials in a society that continues to valorize them at a huge premium. The most effective way to run that racket has been to shift education to a disastrous “student-centric” model, which treats students — who are ironically on campus because they are insufficiently educated — as the proverbial customers who are always right. If the administrators do this even somewhat well, largely passive trustees will avoid asking any hard questions, happily approve higher executive pay and perks, and congratulate themselves at shitty retreats on the great “leadership” and “vision” they discovered in whatever bloated riverboat shyster they installed in a wood-paneled president’s office.

Professional education, meanwhile, has been reduced to little more than an at-will service occupation staffed by a poorly paid corpus of low-level paper-pushers who obediently process information. Even tenure is no longer much of a guarantee. In May 2022, Princeton fired the award-winning tenured classics professor Joshua Katz, ostensibly for not having fully participated in a university investigation, but more likely for having publicly opposed racist faculty demands. In July, University of Pennsylvania law dean Ted Ruger recommended “major sanctions” — possibly including termination — against Amy Wax, also award-winning and tenured, for alleged public statements of opinion that Ruger claims caused “harm” to his Ivy League university community.

As for Jones, a group of his departmental colleagues complained to NYU that his dismissal has set “a precedent, completely lacking in due process, that could undermine faculty freedoms and correspondingly enfeeble proven pedagogic practices.” They are certainly right, but there is no indication that NYU cares, or should have any reason to care. That’s even though the woke boomer hypocrites who edit the New York Times are apparently worried enough about the quality of their future health care providers that they ran a front-page story about Jones.

Within the campus gates, however, Jones’s supporters can simply be ignored. If they are unhappy with their former colleague’s mistreatment, they can leave at no great loss to NYU. Indeed, losing senior professors presents a net gain for universities, which can replace them with lower paid junior faculty hires, even lower paid contingent faculty, or, as is increasingly the case, not at all. Losing award-winning teachers is even better, for they command loyalty outside the administration and can communicate effectively in the media. For virtually all salary-dependent faculty members, the only lesson of Jones’s sad fate will be to sit down and shut up.

“I don’t want my job back,” Jones, who is eighty-four, told the Times. “I just want to make sure this doesn’t happen to anyone else.” But it will. Over and over again.