The long-serving New York Times opinion writer Nick Kristof apparently now wants to be governor of Oregon.

The 62-year-old media superstar seems to be a rather changeable sort of chap. It might almost seem he’s one of the many New York-area residents to have had their identities stolen. Perhaps it was an old platinum credit card, carelessly tossed in a Midtown trash can, which allowed the criminals to strike, or perhaps the purchase over the phone of a first-class air ticket to one of the exotic locales his business frequently takes him.

Whatever it was, it’s difficult to reconcile the superbly cerebral, crusading double Pulitzer Prize-winner and regular CNN contributor with the self-styled ‘Oregon farmboy’ with his finger firmly on the Beaver State’s troubled pulse.

Of course it’s a nice arc for Kristof to travel, from his humble beginnings in the rural outpost of Yamhill, Oregon, the son of two professors at Portland State University, through Harvard and Oxford, then 37 years in the salt mines of the Times, before returning to his roots. It reminds you of Cincinnatus returning to his plow. One or two critics have raised the churlish technicality of whether Kristof meets Oregon’s three-year residency requirements to run for office, but he insists he does. Other than that, he’s kept uncharacteristically tight-lipped on the whole campaign. “I’m afraid that for now I’m trying to do more listening than talking,” Kristof has announced, already sounding a bit gubernatorial. “I’m focused on uniquely Oregon issues rather than national ones,” he adds.

And perhaps that’s the interesting thing. The truth is that there are really two Oregons. There’s the one centered around Portland and the state capital 40 miles down the freeway in Salem, where the legislature busily turns out new initiatives on widows, orphans, the racially oppressed, the poor, the maimed, the halt and the blind. And there’s the other one that’s a vast hinterland of bucolic hamlets and spruce little seaside towns populated by poor rubes who run up a US flag outside their neatly whitewashed houses each morning and generally prefer to rely on themselves than the state. I know. You take most 98,000-square mile entities and you’re apt to find a bit of variety in the mix. But in Oregon it’s almost like a case of schizophrenia. The place is as wildly contradictory in its way as Nick “Farmboy” Kristof is in his.

Other than that, is he well qualified? On the one hand, Kristof’s both formidably brainy, and not exactly a martyr to false modesty. “I’ve gotten to know presidents and tyrants, Nobel laureates and warlords while visiting 160 countries,” he informed us when announcing his retirement from active journalism. He recently co-authored a book, Tightrope, about America’s underlying crises. He’s revered in his trade for his coverage of social issues, touching on everything from the Rwandan genocide to the incidence of flame retardants in furniture. No less than Mia Farrow has remarked: “Every once in a while a moral giant appears among us. Nicholas Kristof is that person.” For years the Times even ran an annual “Win a trip with Nick” competition, enabling would-be journalists to fly around the world and display their empathy. All good credentials.

On the other hand, would any halfway informed American voter ever elect a loudly opinionated non-politician to serve as their chief executive? What kind of crazy talk is that? The Trump model aside, the job’s surely not so much about nonstop bloviating as it is about administration. As one Times staffer remarks, “What sort of management experience does Nick have? Aside from managing his assistant.” Does Kristof really want to give up the life of a globetrotting metropolitan newspaper columnist for the thankless job of schmoozing provincial legislators and micromanaging state budgets? And other than the modern fetish of “listening,” what does he have to offer the voters on those “uniquely Oregon” issues?

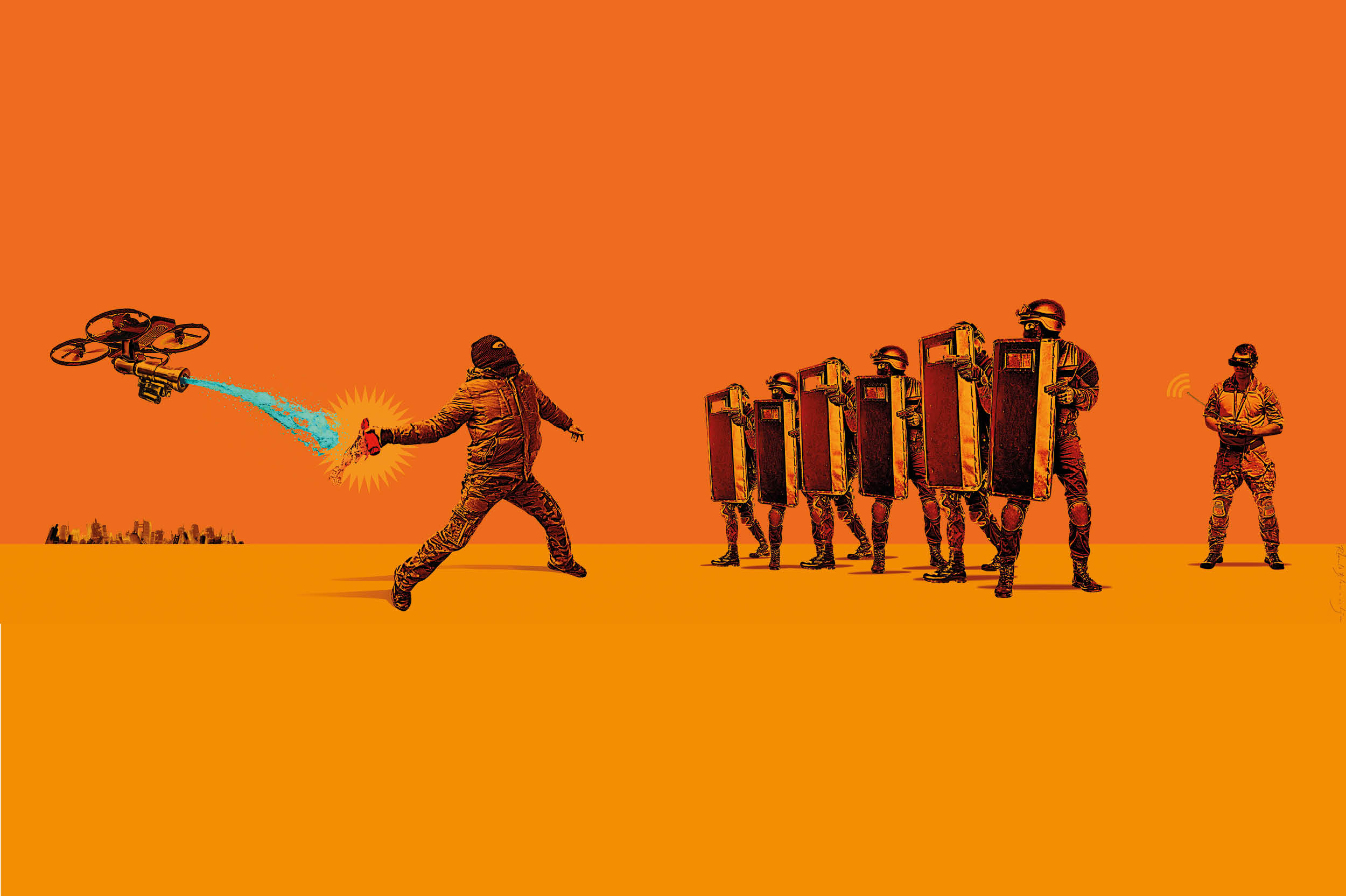

Take Portland, for instance. America’s so-called Rose City has been in a more or less permanent state of siege since the moment Derek Chauvin fatally pressed his knee into George Floyd’s neck in May 2020. Portland celebrated Independence Day that year in unusual style. The police twice declared a downtown demonstration to be a riot over the July 4 weekend. In the measured words of chief of detectives Chuck Lovell, “Officers responded when [protesters] threw bricks, mortars, M-80 firecrackers and other flammables towards them.” He added, “Portland deserves better than nightly criminal activity that destroys the value and fabric of our community.”

These are words of wisdom unlikely ever to pass the lips of Portland’s gloriously feckless mayor, “Tear Gas” Ted Wheeler, whose city currently has all the allure of Berlin after a particularly hard night in April 1945. Portland has achieved an unenviable record 67 homicides so far this year, surpassing its previous full-year total of 66 in 1987, which is twice as many as its larger neighbor Seattle. With such traditional gangland festivities as the Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays still before us, it’s a fair bet that Portland, once known for its trim clapboard houses and artisanal coffee bars, will continue on its way to becoming the Dodge City of the Pacific Northwest.

Nick Kristof’s reaction to this? “At the end of the day, what made Oregon work is a practical, empirical approach to solving problems,” he recently told Portland’s KGW TV station. “And I think that is going to start with mutually acknowledging weaknesses in the context of the glories of this state. I think that’s the way forward and that’s the Oregon way forward,” he concluded.

No, I haven’t a clue what it means either.

Oregon’s current governor Kate Brown is term-limited, and the Democratic primaries to nominate her successor candidate are set for May 2022. In what’s likely to be a crowded field, a winner could emerge with only around 30 percent of the vote. It doesn’t seem an insuperable target for a sharp operator like Kristof. That would pretty well be lights-out in the November 2022 general election, because Oregon hasn’t elected a Republican governor since 1982, the second longest period of Democratic control in the country. In 2018, Brown won election by nearly eight percentage points over her GOP challenger Knute Boehler, who had the advantage of embodying two all-consuming American obsessions by being a local sports star-turned-physician. As another snapshot of the two Oregons: in metropolitan Multnomah County, which includes Portland, Biden won in 2020 by 79.8 percent. About 250 miles southeast in rural Grant County they went for Trump by 77 percent. Perhaps it’s no wonder there’s a movement afoot for five Oregon counties to secede from their state and join Idaho instead.

Unsurprisingly, Kristof’s reaction to Oregon’s existential crisis tends to be on the progressive side. In July 2020 he wrote a piece anguishing about the nightly orgy of looting and arson that continues to distinguish the state’s principal city. “I’ve been on the front lines of the protests here, searching for the ‘radical-left anarchists’ who President Trump says are on the streets of Portland each evening,” Kristof wrote, before concluding: “Provocateurs are found in both the streets and the White House.”

Elsewhere, Kristof falls back on standard greeting-card pleas for universal peace, and the need to “reimagine” the approach to policing our streets, among other views only a rich radical could afford to hold. That same “reimagining” would presumably cost the people of Oregon quite a bit. But there again it’s an interesting fact of modern politics how many voters will tolerate being bribed with their own money. Kristof may connect with the current mood in at least metropolitan Oregon, but perhaps even there they might question the judgment of someone who would forego his semi-divine status at the New York Times to be a mere state governor, and for that matter wonder why any sane individual would want to run for public office in the first place.