Top Democrats took a media victory lap last weekend, crowing about the $1 trillion infrastructure bill that finally cleared the House on Friday night after months of false starts and intra-party squabbling. The vote came only after Speaker Nancy Pelosi, in her latest Hail Mary, attempted to satisfy progressive lawmakers by also allowing a procedural vote on the massive social spending bill craved by liberals. Even then, Pelosi was forced to rely on a handful of Republicans to secure a majority.

Predictably, the White House was eager to spin the bill’s passage as major win for the Biden agenda, claiming it would energize voters and pave the way for trillions more in government spending just in time for the holidays. And yet, despite the high fives and happy talk with reporters, many congressional Democrats will surely spend this week’s recess reflecting on the months of chaotic leadership that preceded the vote. Some will no doubt conclude, if they haven’t already, that they are watching a speaker in decline and a leadership team losing its grip on its own party.

For House Democrats, who face voters in less than a year, that’s an uncomfortable place to be.

While there has been some handwringing on the right over Republican House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s inability to keep 13 of his members from voting for the bill, such criticism overlooks a political reality. As others have noted, infrastructure was always destined to reach the president’s desk, with or without Republican support. Even if reconciliation talks broke down and the entire process became unsalvageable, Democrats were never heading into the midterms without at least one more legislative achievement. Faced with a binary choice of spending less money than they had hoped for or spending nothing at all, it was a safe bet that eventually progressives would opt for the former.

Pelosi, meanwhile, had two major responsibilities throughout this ordeal: keep reconciliation linked to infrastructure or, failing that, get the infrastructure bill done before last week’s Virginia election. She accomplished neither. The first task, keeping the bills linked, had long been a sticking point for House progressives. The infrastructure bill was conceived, after all, as a way to separate the somewhat saner “roads and bridges” portion of Biden’s agenda from his greater fantasy of raising taxes and remaking American society as some kind of modern-day FDR.

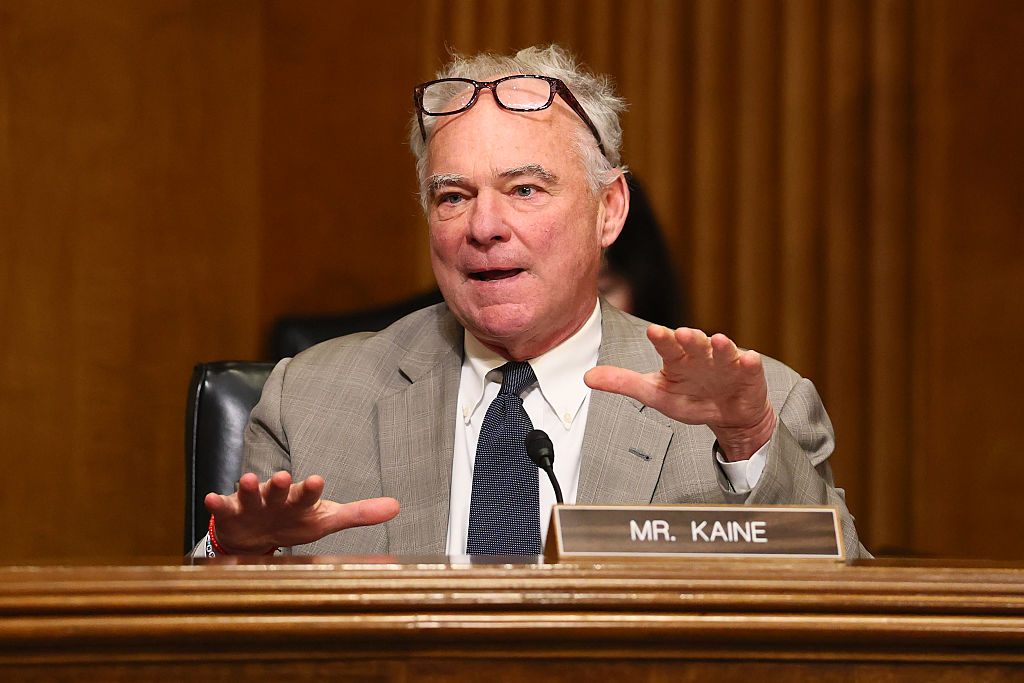

Progressives were understandably worried that if the infrastructure side passed first, moderate Democrats, particularly Senators Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, would get cold feet on the crazier tax-and-spend side and kill the reconciliation effort entirely. At first, liberals demanded that both bills pass together. Soon after, they insisted only on a framework that Manchin and Sinema had signed off on.

In the end, all they got was a procedural “rule” vote and a promise from House moderates that they would support reconciliation if the Congressional Budget Office gave the bill a favorable price tag. By delinking the bills and allowing the infrastructure package, which Manchin helped negotiate, to pass on its own, Pelosi gave the West Virginia senator about 1 trillion more reasons to put a “strategic pause” on reconciliation.

Meanwhile, if infrastructure was indeed going to move first, many Democrats must be wondering why it couldn’t have happened in time to salvage Terry McAuliffe’s lackluster campaign in Virginia. McAuliffe himself had lobbied his friends in Washington to pass infrastructure in time, believing it might inject some life into the state’s deflated Democratic electorate. Yet despite pleas from both Biden and Pelosi, progressives remained unwilling to budge, and McAuliffe was upset by Republican Glenn Youngkin.

The question of whether a bipartisan infrastructure bill could have saved McAuliffe is now academic. Still, some Democrats are beginning to wonder aloud if GOP gains in Virginia and elsewhere are a warning from voters, already fed up with inflation, not to overreach on new spending. If so, Pelosi’s track record should give vulnerable Democratic incumbents little comfort. Those who have been around long enough surely recall how the speaker twisted arms back in 2010 in order to get Obamacare across the finish line — even after Republican Scott Brown won a stunning upset to fill Ted Kennedy’s Senate seat in deep-blue Massachusetts.

Rather than heed Brown’s election as a warning, Pelosi and Obama barreled ahead with Obamacare. In turn, voters in the 2010 midterm elections handed Democrats a historic shellacking. Republicans netted 63 seats and took control of the House — though Pelosi kept her leadership post.

The lesson, at least to dozens of Democrats who found themselves looking for jobs, is that Pelosi will always prioritize progressive legacy-building over her own members’ political futures. Whether or not it’s wise politically, the speaker is committed to finding a path for more spending before the end of the session. Entering her thirty-sixth and likely final year in Congress, it would have been foolish to assume otherwise.