Arching out across a quiet Balkan valley, Montenegro’s first highway cuts across the rocky scrubland with unnatural precision: a modernist stroke of concrete that gleams against the stony outcrops of the Dinaric Alps. Hung on one of the vast gray pillars is the country’s distinctive crimson banner, a golden two-headed eagle at its center. The project may bear a symbol of the young post-communist state but those living in the village beneath know who’s really behind the freeway. The Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia has faded but the communists are back.

Montenegro is struggling to repay a $1.2 billion Chinese loan for the highway’s construction, built to connect the port of Bar with neighboring Serbia. Much of the project remains incomplete. Now the country’s debt has inflated to 103 percent of GDP, with Beijing owning nearly a fifth of its total loan book.

It was hoped that the freeway would prove a vital regional trade link. Montenegrin roads are notorious for their dilapidated condition and frequent fatalities. But Western financial institutions were unwilling to support the project, unconvinced of its fiscal viability. Instead, the Chinese Exim Bank provided a loan, while the state-owned China Road and Bridge Corp was brought in as a contractor.

Construction was a nightmare from the start. Thanks to the inhospitable terrain, engineers planned to build a total of 40 bridges and 90 tunnels. Delays quickly became the norm. Now the inevitable corruption allegations have weakened the projects already brittle foundations. Work that wasn’t carried out by Chinese builders was allegedly sub-contracted out to those with ties to President Milo Đukanović. Unesco too has criticized the project for the environmental effect on the protected Tara River.

Meanwhile, the EU has until recently refused to assist in restructuring the debt — just as the country goes through the process of accession to the bloc. Montenegrin society had been shocked by Brussels’s brusque treatment. There are now reports that Brussels has gone to German, French and Italian development banks in the hope that they can bail out the country with indirect financial aid.

Officials had always expected some problems but calculated that the subsequent economic growth would absorb much of the debt. But like many projects, the pandemic has had unforeseeable consequences. Montenegro is an economy that is deeply dependent on tourism. With vacationers barred from visiting the Adriatic country, the economy has shrunk by 15 percent of GDP. Last year’s elections brought in a new government, ending the three-decades of illiberal rule by Đukanović’s party.

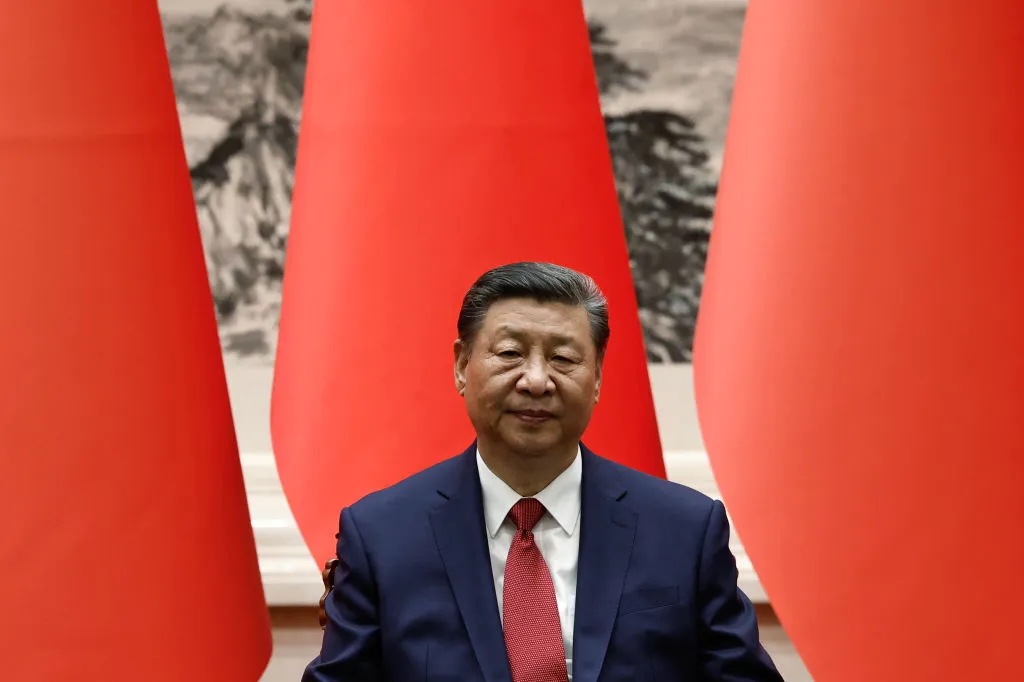

There are two ways China can now proceed. The first is so-called ‘debt-trap diplomacy’ where China directly acquires critical infrastructure in a country that is unable to service its debt. That is how in 2017 China got a 99-year lease on a strategic Indian Ocean port in Sri Lanka. The same could happen to Bar port in Montenegro. China already owns Piraeus Port in Greece — Europe’s seventh largest harbor.

The second strategy is to offer Montenegro debt restructuring but in exchange China will seek political loyalty from Montenegro. That loyalty would mean more work for Chinese state-owned companies and voting at international institutions in China’s favor. Montenegro is, after all, a Nato member state. In both cases, China wins, Europe loses.

There is, of course, a sound business logic in the EU’s reluctance to assist with debt involving third parties. And officials in Brussels have suggested that even if they did attempt to directly restructure the debt, the Chinese would somehow seek to block the move.

However, the case of Montenegro is not one of commercial contract law but of geopolitics. When it comes to China, the EU is not dealing with an actor who plays according to the technocratic rules set down by the Brussels bureaucracy. It is dealing with a rising global power that is using economic statecraft to expand its global clout across the Eurasian supercontinent, including at its European edge.

Europe is showing the Balkans that it is willing to criticize collaboration with the likes of China but showing too that it is unwilling to push back. In late May, Chinese president Xi Jinping had a phone call with Đukanović where the two discussed bilateral ties. Unlike the EU, China knows that it has leverage over Montenegro and is eyeing up the right opportunity to use it. Brussels has been late to realize that it too can pick up the phone. The EU needs to demonstrate that it is capable of protecting its interests while sending a message to the Balkans that Europe has its back. Otherwise, Montenegro will be easy prey for China — and the EU’s strategic credibility with it.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.