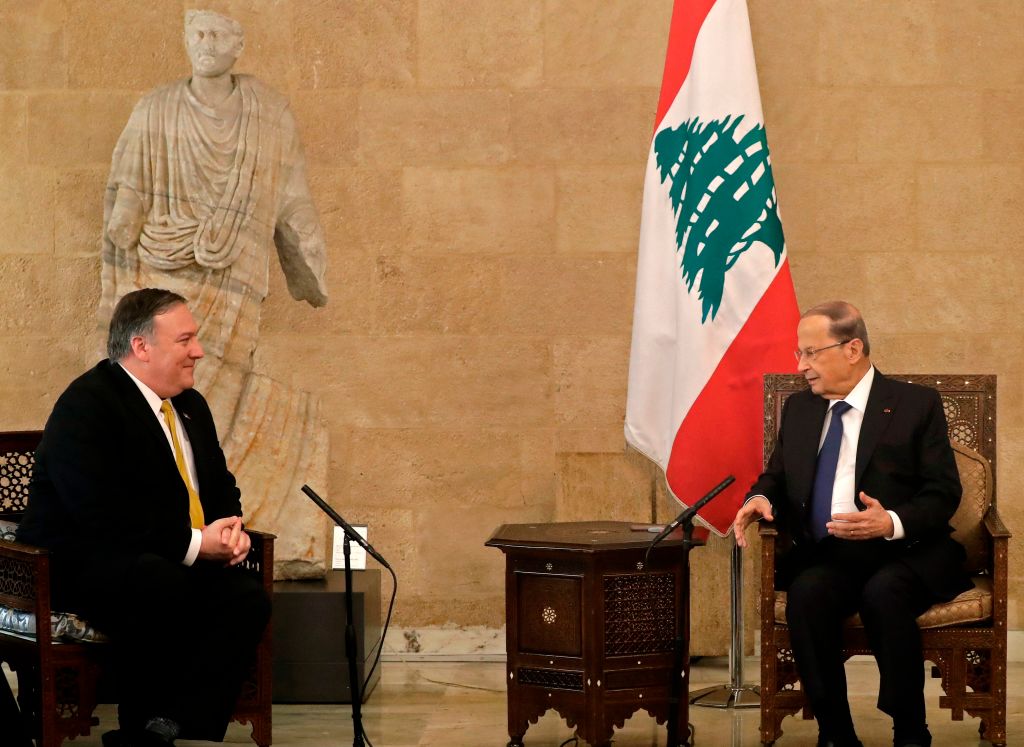

Identity politics has long been the cornerstone of Lebanon’s constitutional system. Seats in parliament and jobs in the government bureaucracy are divided between Christians and Muslims, with a Maronite Christian serving as president, a Shi’ite Muslim as the speaker of the parliament, and a Sunni Muslim as the prime minister.

Despite a long and bloody civil war, not to mention major changes in the demographic balance of power, this system has survived more or less intact since 1943.

Although no official census has been conducted since 1932, the general agreement is that Christians now constitute around 40 percent of the citizens — and Maronite Christians less than 30 percent — and that the percentage of Shi’ite Muslims in Lebanon is now higher than that of Sunni Muslims.

In short, Lebanon today remains a loose federation of religious sects and tribal groups that has continued to engage in zero-sum political competition for power and resources, including by winning the support of regional and global players.

In fact, contrary to the fantasies of European imperialists, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and the other artificial constructs or ‘states’ that were formed in the Middle East in 20th century, have failed to give birth to new nations which leave behind the vestiges of sectarianism, ethnicity, and tribalism and adhere to western notions of citizenship and democracy.

In a way, much of the Middle East has been Lebanonized in the aftermath of the America’s regime changes and nation building crusades and the ensuing Arab Spring, demonstrating that there are no Iraqi, Syrian, Libyan or Yemenite nations. Instead, there are Arab-Sunnis and Arab-Shiites, Kurds and Druze, Assyrians and Turkmen, Yazidis and Armenians, Maronites and Copts, and the long list of tribes fighting for power in Libya and Yemen.

And let us not forget that even in the modern state of Israel a fragile balance of power is being maintained between two ethnic-religious communities, a ruling Jewish majority and an Arab minority.

There is therefore a certain irony that American liberal intellectuals, who have been day-dreaming that their imagined communities in the Middle East would eventually turn out to be ‘like us’, have been promoting an ambitious political agenda in the form of identity politics that could potentially make the United States a lot more like Lebanon.

The first candidate of ethnically Jewish heritage to be nominated for President by a major American party was conservative Republican Barry Goldwater in 1962 (his father was Jewish and he would have been regarded as a Jew based on Israel’s Law of Return), and as far as I know, the number of Jews who had voted for him that year would have probably not constituted a Minyan (a quorum of ten men required for traditional Jewish public worship).

But then according to news reports, Muslim and Jewish Democratic members of Congress have been holding a series of meetings ‘to ease tensions and find common ground’ in the aftermath of the recent divisive remarks of Rep. Ilhan Omar of Minnesota, a Hijab-wearing Muslim of Somalian descent who suggested that American supporters of Israel on Capitol Hill and elsewhere have an ‘allegiance to a foreign country.’

In a scene that could have probably taken in a Middle Eastern parliament, one of the meetings ‘ended with one lawmaker in tears,’ reported the Washington Post. Muslim members of Congress complain that there are too many Jews on the House Foreign Relations Committee and demand to set a ratio of 6-to-5 of Jews and Muslims there? And the ratio would have to change as the percentage of Muslims in the population rises.

Does that sound preposterous and un-American? Why? We have now seemed to have accepted as a given that the Democrats would probably not nominate a white man as their presidential candidate and that a person of color (POC) would have to head the ticket, and if, say, Joe Biden or Beto O’Rourke do get nominated, it goes without saying that their VP pick would have to be a POC.

And if that POC was an African American, expect an outcry from the Latinos who would then probably demand guarantees that member of their community would be appointed to State or the Supreme Court, which in turn could antagonize Asian Americans and would require a response that would ensure that that community would be represented.

And is there really a big difference between the Lebanese system that allocates positions in the government bureaucracy based on membership in a religious sect to American affirmative action programs that guarantee that certain percentage of government jobs as well as college admissions to specific ethnic and racial groups? At least, when it comes to Lebanon, you know who is a Muslim and who is a Christian. But how do you decide whether someone is an ‘Hispanic’ and whether a biracial person should be considered as an ‘African American?’ Maybe America will some day soon have to change its constitution so that, like Lebanon, it can keep a balance of power.