Poland

“Biden fell asleep.” Perhaps a thousand jokesters posted this and similar jibes in the livestream comments as we waited for the president to speak from Warsaw. Thousands of Poles, and doubtless many Ukrainian refugees, were gathered around the Royal Castle in the center of the Polish capital to wait.

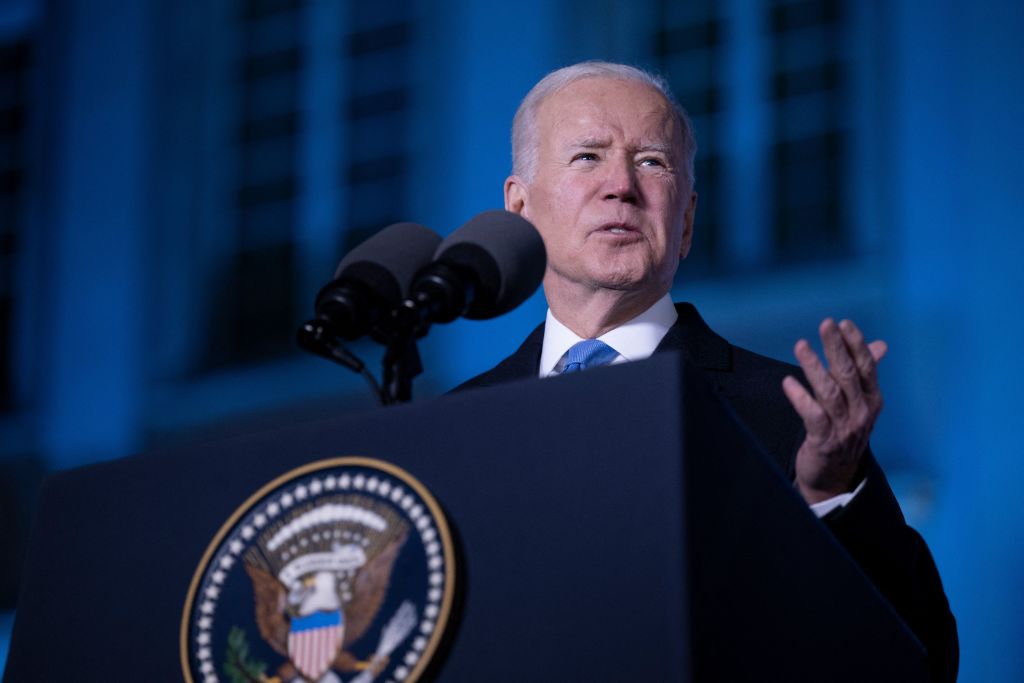

Biden trotted out — old but amiable and very much awake. In fact, after spending two days meeting refugees, Ukrainian representatives and Polish politicians, he looked surprisingly sprightly.

God help me for saying this but I have a soft spot for the president. Perhaps it’s because I inadvertently gave him his winning campaign strategy (OK, I cannot prove that anybody on his team read my article “The case for locking Joe Biden in a cupboard,” but it certainly appeared as if they did). Perhaps it’s because he is old and vulnerable.

But he spoke quite firmly — and sometimes eloquently. “Be not afraid,” he said, quoting the Polish Pope John Paul II, “It is a message that will overcome the brutality of this unjust war.” It is a good one.

Another reason I have some time for President Biden is that he has been resisting calls for military escalation between NATO and Russia. When he was asked, in Brussels, if he had ruled out armed intervention prematurely and emboldened Putin he replied, with fitting crankiness, “no and no.” (Before the invasion, in another valid outburst of Trumpian disdain, he responded to a journalist who had asked him why he was waiting for Putin to “make the first move” by saying, “What a stupid question.”)

In Warsaw, Biden emphasized again that he had no intention of pitting American troops against those of Russia. Calls for a “no-fly zone”, or, as the Polish government has been advocating, a peacekeeping mission in Western Ukraine, make us vulnerable to the initiation of conflict between Western and Russian troops that could spiral into the territory of mushroom clouds.

Still, Biden did end his speech by saying, “For God’s sake, this man cannot remain in power.” This was quite the statement — and quite the shift in messaging. It sat uneasily, like a gun on a kitchen table, without its presence being explained. How did Biden intend to pursue Putin’s removal, if indeed he did? We had no answers. Naturally, the White House hurried out a statement:

“The president’s point was that Putin cannot be allowed to exercise power over his neighbors or the region. He was not discussing Putin’s power in Russia, or regime change.”

This is not how anybody understands the phrase “remain in power”. Did Biden stray from his script or did he want to keep Putin guessing? You be the judge.

Elsewhere, the president talked a lot about how this was “the latest battle in a long struggle.” “This battle will not be won in days, or months either,” he said. Did he mean war in Ukraine or a general endless struggle against Putin? The distinction matters — especially if you are Ukrainian or if you are in the Middle East or Africa, counting on this year’s harvest in Russia and Ukraine.

Biden’s rhetoric was reminiscent of the Cold War — or, at least, our memories of it. “Liberty” and “democracy” face “autocracy”. Freedom of the press and freedom of assembly were among the endangered values Biden mentioned. Well, I support both of those things as well but the more immediate principle at stake is the freedom to live in your own home, at peace, in an independent state.

Big talk of ideological conflict also invites the Chinese to align themselves more firmly with the Russians. This is not a bifurcation we should haphazardly draw if we don’t wish for a local struggle with one superpower to escalate towards a global struggle with two. Of course, we know the Chinese will be looking on while weighing up their options with Taiwan. But our emphasis shouldn’t be on democracy as much on mind your own damn business — or get hurt.

Biden’s words on the war itself were more compelling. His praise for the Polish people who have shown such generosity towards refugees went down well (though Moldovans, Romanians, Slovakians, Hungarians et cetera deserve praise as well). Taking some food donations to a volunteering point in my unassuming Silesian town this afternoon, I was struck by the urgency of work even in a provincial place like ours. More international support will be welcome.

Biden spoke movingly about talking to refugee children who asked him if their fathers and brothers would be OK. “You, the Russian people,” he said, shifting his focus, “still have memories of being in a similar situation.” The war, Biden said, “is not worthy of you.” True — and Biden also sounded stronger than he sometimes does when he told Vladimir Putin, “Don’t even think about moving onto one inch of NATO territory.”

Biden is not the most intimidating leader (who could be while knocking on the door of eighty years old?) but Putin, with his vast table, his disappearing advisors and his strange ramblings about cancel culture, hardly looks like a pillar of strength. It would be nice if leaders realized the dangers of unshackling forces beyond their control. The US has been guilty of doing as much before — but that in no way excuses Putin doing so now.