President Biden’s description of President Putin as a ‘worthy adversary’, in advance of their summit today, was a sensible move. On the one hand, it restores the basic civility necessary for any diplomatic exchange, after Biden’s unfortunate ‘killer’ remark. After all, the conduct of international relations by a superpower is a serious matter — and part of Biden’s own international prestige lies in his restoration of dignity to the US presidency after the flamboyant excesses of Trump.

The ‘adversary’ remark also emphasizes the adversarial nature of the relationship and shuns the absurd and discredited language of ‘partnership’ and ‘looking into Putin’s soul’ engaged in by previous presidents (even if Biden, before becoming president, claims that he told the Russian leader he didn’t think he has a soul.)

Most of all, the statement is accurate. If US-Russia relations are to be viewed in realist terms as a competition of US and Russian national interests (which is how all members of the Russian establishment and most members of the US establishment have seen them for the past 15 years or so) then Putin is indeed a worthy adversary: a ruthless and skillful defender of Russian national interests, who on the whole has played a series of weak hands with considerable skill.

To understand the strength of Putin’s position when it comes to defending Russian international interests (as opposed to domestic interests, where his deeply corrupt set-up is becoming increasingly unpopular), it is vital to understand that while Putin is obviously much more personally powerful than Western leaders, he is still the leader of the Russian foreign and security establishment — or as former Obama adviser Ben Rhodes dubbed the US equivalent, a blob.

Every major country has such a blob, which conducts national foreign and security policy on the basis of certain relatively fixed and enduring beliefs (often virtually dogmas) national interests and their country’s place in the world. These beliefs may seem strange and irrational to outsiders (including some of their own fellow citizens), but generally stem from deeply-held sentiments of national identity and historical experience. It can be a form of patriotism.

Russia’s blob is determined to maintain Russia’s role as a great power on the world stage (which may lead Russia into an even more dangerous dependence on China); to exclude potentially hostile foreign alliances over Ukraine, Belarus and Georgia, and to defend the minorities in those countries that look to Russia for support.

There has therefore been nothing at all unpredictable about the basic contours of Russian policy towards Ukraine. Seen from Moscow, the country is a vital Russian national interest, one for which Russian will if necessary fight — just as the US will do whatever may be necessary to exclude hostile great powers from Central America.

Insofar as the West has committed itself to the expansion of Nato and the EU to these countries, a clash with Russia was therefore inevitable and that is not down to just Vladimir Putin. The same is true of the desire of the US establishment — expressed through state-funded institutions like Voice of America, Radio Liberty, the National Endowment for Democracy and so on — to bring down the Putin regime and thwart Russia’s attempts to influence the US political process.

On these issues, all that can be done (as during the Cold War) is for the two sides to make clear the red lines beyond which they will respond with the harshest countermeasures: the US with greatly increased sanctions, Russia with intensified military intervention in its neighbors. The expression of these mutual red lines is the most important goal of the present summit.

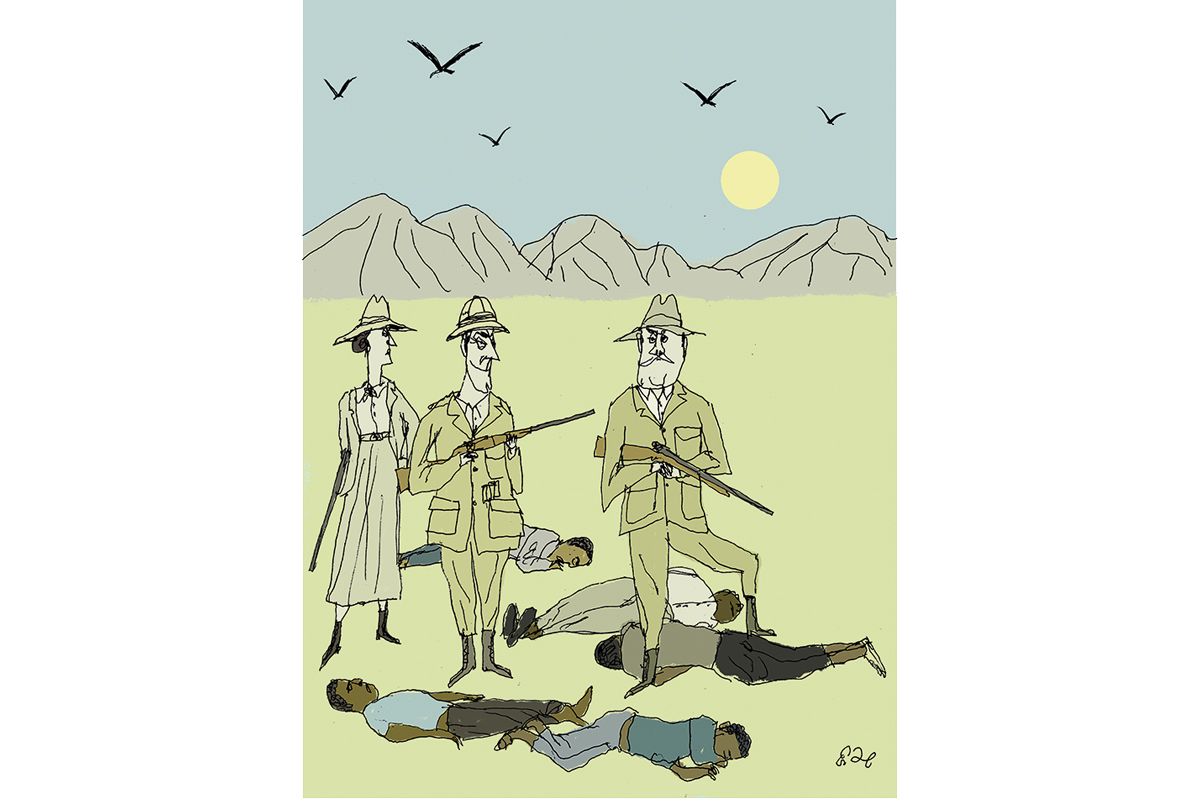

Elsewhere there should be room for cooperation. In the Muslim world, a few things are important to note if US-Russian relations are to be placed in their proper perspective. The first is that in this region — whatever may be the case elsewhere — the US claim to represent a rules-based order and to spread democracy and freedom is bogus, if you look at the historical record. Many of my Arab students want alliance with the US, for their own good national reasons. Not one of them, in seven years, believes in a US commitment to spread democracy. Why on earth should they? In the Middle East, the moral playing field between the US and Russia is a level one.

Finally, it should be noted that on the most important issues in this region over the past 20 years, the US has been proved wrong and Russia has been proved right (sometimes together with France and Germany). The US invasion of Iraq and its overthrow of the Libyan state proved catastrophic. If the Bush administration had sought a nuclear agreement with Iran in 2002, as advocated by Russia, they would have got a far better deal than anything that is possible today. A US destruction of the Baath state in Syria would have been a triumph for Isis. So if in certain areas, US hostility to Russia is hard wired and may be justified; in others, a degree of US humility is in order — and would certainly be a better basis for Joe Biden’s approach this week.

Anatol Lieven is a professor at Georgetown University in Qatar and a senior fellow of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft in Washington DC. He was formerly a British journalist in South Asia and the former USSR. His latest book, Climate Change and the Nation State, has just been published in an updated paperback edition by Penguin.