We don’t really negotiate much in the US and so we’re bad at it.

The American style of negotiating is to demand everything and settle for nothing less. We ask for an outrageously large amount and “bargain down” after the other side offers an equally outrageous small amount. Starting anywhere near your actual number is considered a sign of weakness.

We don’t like gray areas and we don’t like to feel like we’ve lost out on something. So being asked to support something that on its face seems reasonable, like allowing two people in love living together in a home they co-own to marry, means buying into a whole LGBTQIA2+ agenda that somehow includes forcing kids to listen to drag queens read stories aloud about sexually ambitious caterpillars and their same-sex tadpole pals. Seeking reasonable restrictions on abortion ends up cruelly forcing rape and incest victims to carry to term.

We do the same thing in broader swaths, when people who misuse pronouns or support the Harry Potter author are not just sidelined or argued with, but canceled, deleted, defunded, disenfranchised, thrown down the memory hole. The presumption is that even on the most ideological of arguments, there is a clear right and wrong only. We have evolved speech to match this mindset, phrases like “my way or the highway” or “all or nothing.”

Back in the day, when I worked for the State Department, every summer embassies abroad had to ask for temps to help us catch up on clerical work. There was only so much money around and not everyone could get everything they wanted. At first I did what was standard, ask for ten people knowing I only needed five, with all sorts of silly justifications I had to eventually walk back. One year I played it different. I wrote in detail what five people would do, what would not get done with only four, and why six would be excessive. That year and the ones that followed were the easiest ever: Washington and I jumped right to the meat of the problem and nobody was forced to belittle anyone.

That’s what did not happen recently when Roe v. Wade was overturned. Though Roe was poor jurisprudence and constitutionally hilarious, it was the product of negotiation. First-trimester abortions were basically allowed, second-term were generally allowed, and third was more or less up to the states. Roe produced a workable solution to a very complex problem, uniquely American as it combined religious, moral, and red-and-blue thought into what was often falsely presented as a binary decision — abortion was legal or not. The compromises in Roe were far from perfect or widely accepted. They were simply the output of a beleaguered Court willing to talk about something the rest of America would not.

The problem was Roe‘s supporters and opponents almost from day one set about trying to take a compromise solution and make it an absolute. Blue states latched on to their freedom to dictate third-trimester rules by gleefully promoting gory end-term abortions where a viable baby was aborted. Same on the other side. Clever legal tricks were deployed so that, sure, you can get a first-trimester abortion, only not where clinic regulations and hospital affiliations were manipulated to make it near impossible to meet the standards.

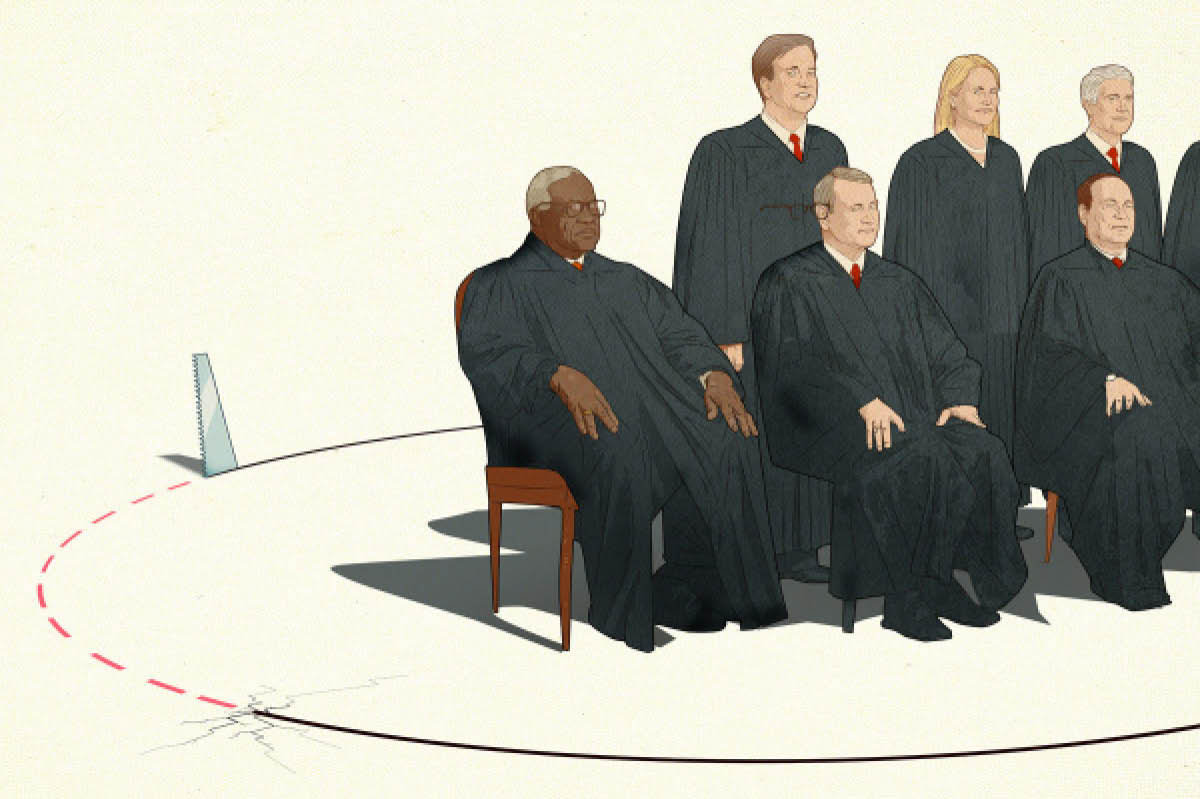

The Court itself is not immune. In combination with the gutting of Roe (another all-or-nothing type decision), Justice Clarence Thomas opened the door to ending federal law allowing for same-sex marriage. If you can’t have all the rights, you should have none of them, he seems to be saying to the left. Specifically, Thomas was threatening Griswold v. Connecticut, a 1965 decision declaring that married couples had a right to contraception; Lawrence v. Texas, a 2003 case making same-sex sexual activity legal across the country; and Obergefell v. Hodges, the 2015 case establishing the right of gay couples to marry.

Has anything changed in society that requires such a new look? No, the only thing that has changed is that a different side now holds a majority on the Court and wants to run with it. They have no more interest in compromise than the demonstrators massing around justices’ homes in the hope of harassing them into compliance with the mob, or of AOC on TV screaming that people are going to die.

Same for gun control, the other recent Supreme Court decision. In New York State Rifle v. Bruen, the Supreme Court again swung widely. The existing law, basically saying the right to bear arms in the 2A did not automatically mean a right to openly carry arms in public, had been misused by anti-gun states.

In Hawaii, for example, every single open carry permit had to be approved personally by the chief of police. Multiple chiefs over a period of recent years found no reason to approve even a single permit and in the past 22 years there have been four open carry permits issued in Hawaii. All or nothing, as if somehow not one applicant in recent memory was capable of safely openly carrying a weapon.

So the response from the now-conservative Supreme Court was to do away with provisions governing carrying a weapon. The counter-response from those states that are anti-gun, such as Hawaii, is to promise to jerry-rig their laws with outrageous training requirements or exorbitant fees to somehow get around the Court’s perceived free-for-all, and to cite recent mass shootings (which had nothing to do with handguns or open carry laws) as fear-inducing excuses. Nobody sees any of the middle ground.

Which is why the Supreme Court’s rulings on abortion and gun carry law resolve nothing. Progressives will simply wait it out until it is 1973 again and the Court is turned over to a more liberal group of jurists who will reinstate black to replace white or vice-versa. The real answer on abortion, a rough and robust debate in Congress followed by a set of compromises, or an equally rough and robust debate at the state level, will never come.

Americans are not very good at negotiating and so usually pay more at the car dealership than they should. The same problem plagues us on much more serious issues and it costs us far more.