Everyone is bullish on natural gas, but I think America’s most inexhaustible resource might be 1990s nostalgia. Every time it seems our BuzzFeed badlands have run dry, another Friends reunion or reassessment of Francis Fukuyama comes gushing through the soil.

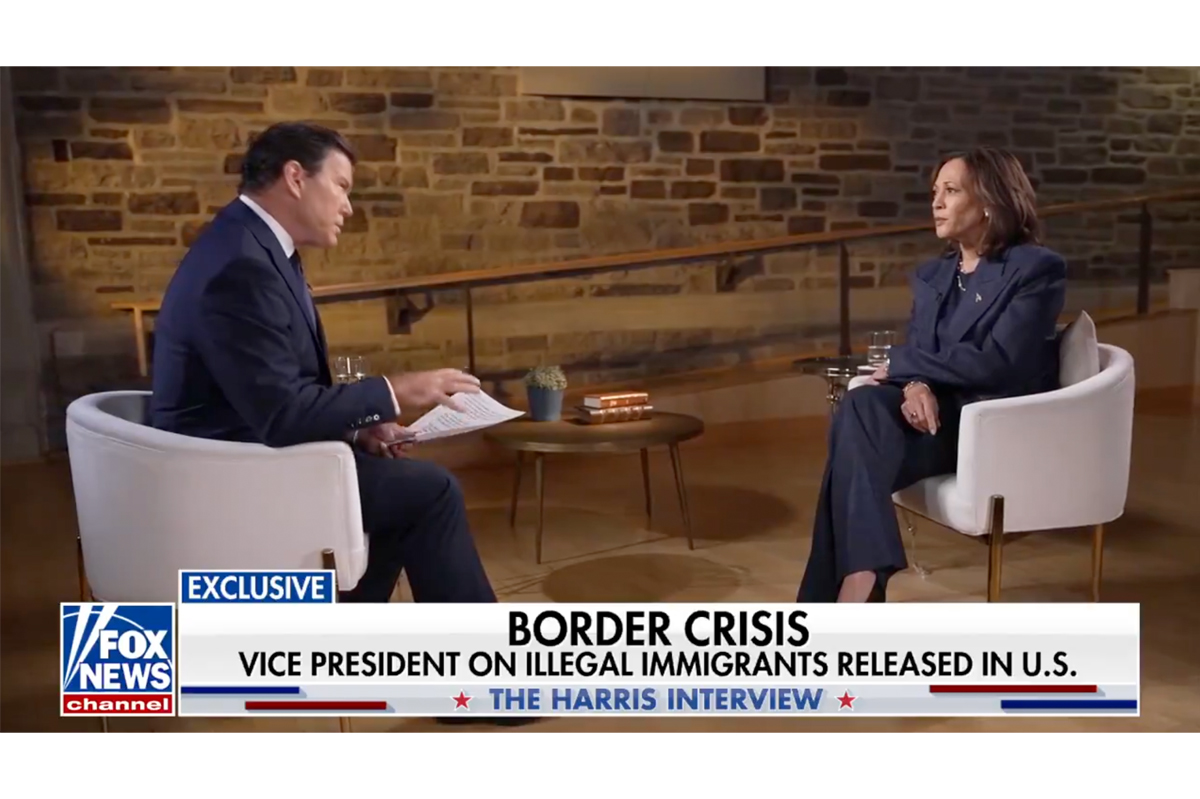

So it is that the most hyped series on TV right now is American Crime Story, dedicated this season to Ryan Murphy’s telling of the Clinton impeachment. Legends of the Hidden Temple, perhaps the most beloved children’s show from the Nineties (and that’s saying something), is being remade for adults. Even the recent death of comedian Norm Macdonald elicited callbacks to the days of cynical wiseasses and O.J. Simpson cracks.

What is it about the Nineties that remains stuck in America’s craw? As a journalist, I sometimes feel out of my depth when I write, but on this topic I’m a bona fide specialist. I was born in 1987, which makes me a quintessential Nineties kid — the decade spanned my first memory to my middle school graduation. Like so many others, I often find myself missing it and, also like so many others, I wonder whether that’s mere nostalgia for childhood or something deeper.

The first thing that comes to mind when the Nineties are mentioned is a certain neon-plastic consumerism. The Sixties had their music and political causes, the Eighties their patriotism and renewal, but my decade was characterized by stuff, towering heaps of it: Pokémon cartridges, Magic cards, Tamagotchis, Moon Shoes, Velcro sneakers, Furbies, Super Soakers, Game Boys, Pogs, Beanie Babies, VCRs, CDs, Fruit by the Foot, Warheads, Foxtails, NordicTracks, Koosh balls, Surge cans, floppy disks, pieces of the Aggro Crag, Pendants of Life, yo-yos, Discmans, pagers.

This was no accident. Demand for stuff was high back then: consumer spending surged throughout the Nineties, boosted by a stock market boom and an increase in productivity after years of concerns that Japanese workers were outhustling Americans. And while a brief recession in 1990 might have sunk George H.W. Bush’s presidency, unemployment would subsequently fall from 7.5 percent in 1992 to 4 percent in 2000. All those bulging shopping carts seemed to herald a new American economy, one in which there wasn’t just a chicken in every pot but the pot itself had four different cook settings and was marked down at Kmart.

There were warning signs that all this might not be sustainable. Unprecedented amounts of credit card debt lurked behind that consumer spending. Economic inequality was widening. The burst of the dotcom bubble in the late Nineties, which wrecked many internet startup companies — what a country we might have been had Pets.com not gone under — showed that the galloping growth could be illusory, that a high-flying stock market wasn’t an ironclad indicator of economic reality.

Onward the prosperity went, and no one much cared to think about what would happen when it ended. The 1990s in retrospect can look like a time of great hubris, or at least complacency. Yet there was genuine justification for feeling this way. The Berlin Wall had come tumbling down, and with it any hope of Marxism displacing markets, or the USSR menacing the USA.

We were king of the hill, to use the title of Mike Judge’s 1997 cartoon series, presiding over a unipolar moment. There were no serious challenges to America’s global power.

Alongside the triumph and triumphalism came the seeming resolution of the social problems that had so often provided grist for anti-Americanism. Crime plunged during the Nineties, putting an end to the ‘Bronx is burning’ violence of the previous two decades which had made America look so unjust to the rest of the world. The cultural fractiousness of the Sixties was long gone, with a concomitant lowering of the national temperature and political stakes. Voter turnout in the 1996 election was the lowest since that glowering square Calvin Coolidge was elected 70 years earlier. It’s too cute by half to say the biggest issue of the decade was a presidential blowjob, but certainly politics back then felt smaller, less consequential.

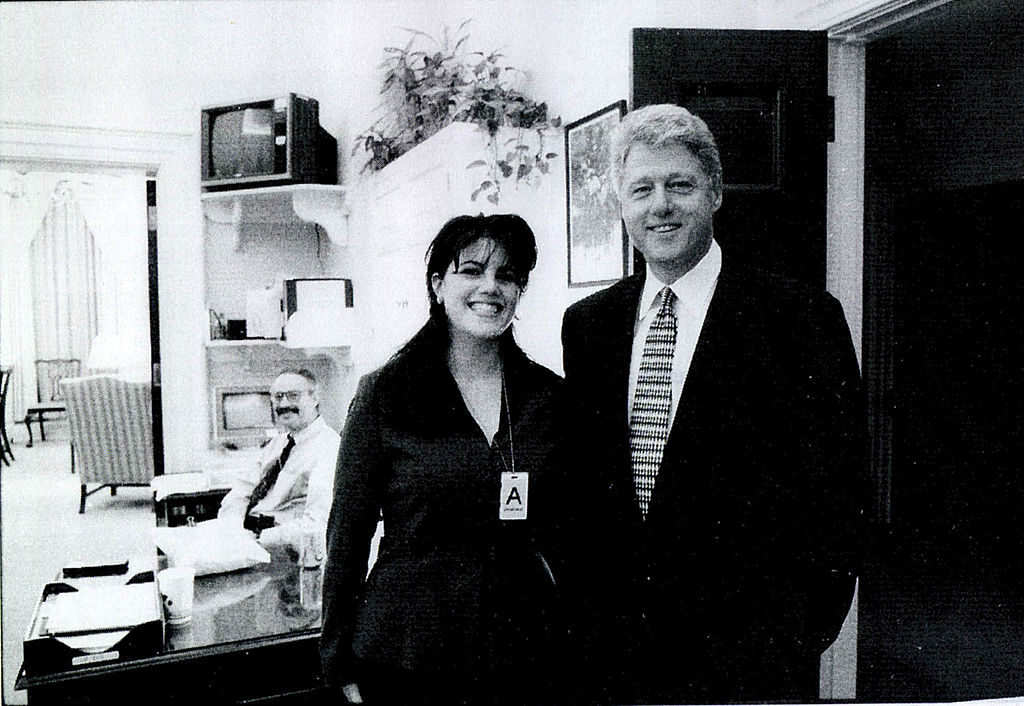

Where Coolidge had been the ironic, taciturn opposite to the giddy 1920s, Bill Clinton was the gigawatt embodiment of naughty Nineties decadence and optimism. The first baby boomer president, the man who couldn’t say no to a 22-year-old intern, Clinton felt more like a cultural skipper than a Coolidge-style night watchman. In line with the decade’s giddy expansionism, he signed into law free trade across North America and deregulated the banks. And while the Monica Lewinsky scandal can seem today like an unseemly outburst of American puritanism, it also presaged much of our modern, smash-mouth, flashbulb politics.

Clinton’s misbehavior didn’t just spawn TV careers for James Carville and Ann Coulter: it hinted at deeper trends. Presidents had had affairs in the past — FDR and Lucy Mercer, JFK and every female who ever passed through his Oval Office — but the public nature of Clinton’s dalliances, and his ultimate survival after their exposure, seemed like nothing less than a ratification of the sexual revolution. The public didn’t just forgive Clinton for Lewinsky; they forgave him for Gennifer Flowers and Paula Jones too. That Clinton should be removed from office was always a distinctly minority view; his approval rating throughout the impeachment process never fell below 55 percent.

America, as it turned out, didn’t mind a little sex in the workplace. Ironically, Clinton had declined to run for president in 1988 reportedly because the former Colorado senator Gary Hart had been torpedoed as a candidate by his affair with Donna Rice. What a difference a decade made. The 1990s had seen the rise of internet porn, Viagra and sex-enamored sitcoms. To say the decade revolutionized or even popularized the carnal would be as cheeky as Philip Larkin claiming sex began in 1963. But Americans certainly become more comfortable with sex, especially as a feature of the consumerism and mass media in which they were saturated.

What all of this amounted to — politically, economically, sexually — was a sense that we had gotten away with it. America was the nation we badly wanted to be: liberal, pluralist, capitalist, thriving at home and respected abroad, trading freely, beaconing to immigrants, shedding at last that old frontier austerity and religious puritanism. Onward, then, into our tech-positive, sex-positive future.

This headiness is where the much-maligned idea of an ‘end to history’ comes swaggering in. The book that popularized the term, Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man, was published in 1992, during the eye-watering national high that followed the Cold War. It’s a more serious work than it often gets credit for, but it does ultimately conclude that American-style liberal democracy is more or less the final answer to all our political questions. A curious irony, that. The eschatology of communism holds that it is the final stage of history. Yet here was Marxism’s greatest adversary, America, exulting in similar terms.

We all know what happened next. This hubris, combined with anger over 9/11, saw us try and fail to democratize the Middle East. The unfettered pursuit of profit and deregulation helped crash the economy into the worst recession since the Great Depression. Technological optimism — few figures were as quintessentially Nineties as Bill Gates — yielded an epidemic of Instagram suicides and a global politics warped by social media. Sex positivity provided cover for the crimes of powerful men. Liberal triumphalism gave way to attacks on free speech. Fiscal prudence yielded a sky-high national debt. The unipolar moment expired as China rose. ‘Decline,’ a once unthinkable word reserved for peak-oil whack jobs and gloomy English historians, sprang naturally off our lips.

From ‘number one’ to ‘are we done?’ in a mere 20 years — and history teaches that nations can unravel quickly. One consequence of 1990s pride was that it prevented us from addressing the underlying problems that might have forestalled some of our unraveling. Yet it would also be trite to say that the decade contained the seeds of our destruction. To insist that things had to end up this way is to subscribe to so much shallow determinism as to be either a fool or a political philosophy professor. Between now and the Nineties lie countless terrible decisions by policymakers which, cumulatively, have squandered our inheritance.

So perhaps there’s something to the nostalgia after all; perhaps it really was a better time. All that’s in the rearview now. We Nineties kids aren’t even the target demo anymore, even if we do know why Apple Jacks don’t taste like apple. Soon enough we’ll be grumbling like reactionaries about the softness of the younger generation. None of these little Gen Z shits could’ve ever put the silver monkey together. (Not that we ever could.)

Yet even allowing that the hidden temple was our Vietnam, the point about the Nineties is that there wasn’t a major war to fight. It wasn’t an end to history so much as a holiday from it, an aberration in our otherwise tumultuous national story. For that reason, perhaps it’s okay that we remember it fondly. There are worse things than memories of afternoons spent playing Super Nintendo in the shade of unreality.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2021 World edition.