A coveted working-class demographic that has been loyally Democratic for generations stands poised to vote Republican in record numbers. Its voters are upwardly mobile, having risen from the deep poverty of their immigrant ancestors to a decent middle-class life. Their incomes are rising quickly and are soon expected to reach the national average. They start businesses at rates that exceed the native born. Recent government data shows them moving into the suburbs from ethnic enclaves in the cities. All of this has coincided with their political shift to the right.

This demographic is family-oriented and deeply religious. Nativist elements have occasionally questioned their loyalty to the United States, but they join the military at rates matching the population as a whole; opinion surveys reveal them to be deeply patriotic, with above average levels of support for the police and the military. Their traditional values stand in contrast to those of the nation’s educated elite, whose shift to the left has alienated them from the old-school, working-class Democratic Party.

As people who have worked their way up, they are deeply suspicious of government handouts to people who don’t work. They draw a sharp distinction between programs like Social Security, which they have paid into all their lives, and recent expansions of the welfare state that hand out benefits regardless of work. If they have worked hard and played by the rules, why can’t everyone else?

And yet they have to date been reliable supporters of the Democratic Party. But at the last election, their support for the Democrats has waned. Since then, the media and Democratic operatives have been obsessed with why. Now, polls show them to be something approaching a swing-voter group. Some even predict that within a few decades they will start voting exactly as the country as a whole does, or even lean Republican.

All this might describe the Hispanic vote in America in 2022, especially with polls that show Republicans competitive for, even tied, with Hispanic voters in this November’s midterms. But all of it is also true of white Catholic voters in the 1960s — once the backbone of the urban Democratic machines in America’s northern cities.

Ethnic politics began almost as soon as the Irish stepped off the boats in the nineteenth century, starting in tight-knit communities organized around the Roman Catholic Church. When they became citizens, their choice of party was an easy one: Andrew Jackson’s Democrats — the “party of the people” fighting against the mercantile interests most closely aligned with England, the colonial oppressor they despised. The next wave of arrivals, from Italy, were harder to wrangle politically, having come from the country’s south, where national government barely existed. They were migrant workers who went back and forth to their country of origin freely, loyal to their local villages rather than any nation or political party.

They all rallied behind John F. Kennedy, who received 78 percent of the white Catholic vote in 1960. Kennedy faced suspicion from the Protestant majority for his “papist” religion, but ultimately won thanks to the children of immigrants who had reached critical mass in the industrial swing states. In the same way, both blacks and Hispanics voted in record numbers for Barack Obama, with Obama’s share of the Hispanic vote reaching 72 percent in 2012.

For white Catholics, and Hispanics fifty years later, it was downhill for Democrats in the elections that followed. A major warning sign came in 2016, when Democrats lost ground with Hispanics, even campaigning against Donald Trump, whose entire campaign seemed premised on offending as many Hispanics as possible. In 2020, having mostly dropped his hard-edged immigration rhetoric, Trump made double-digit gains with Hispanics. So it was in the 1960s, when the white Catholic children of immigrants began their migration to the political center. By 2000, they were voting the same way as the country as a whole. They didn’t stop there: by 2020, Trump was winning the white Catholic vote by double digits.

Both Hispanics and white Catholics also joined the march from the city to the suburbs. Once they arrived, they joined a multiethnic majority no longer defined by sharp neighborhood borders along ethnic lines. In the 1960s, this suburban migration made places like Westchester County and Long Island a Republican counterweight to heavily Democratic New York City. In Texas today, the Hispanic population is growing fastest in higher-income suburbs and exurbs — like Conroe and The Woodlands outside Houston — and dropping fastest in the Hispanic-majority neighborhoods of central cities: In the suburbs, the rate of Hispanic participation in Republican primaries is almost three times higher than in the inner-city neighborhoods they left behind.

Suburbanization has also meant greater economic opportunity. While higher incomes today signal a leftward shift for whites, the opposite is true among Hispanics, where higher income equated to stronger support for Trump in 2020. And overall Hispanic income levels are rising quickly, jumping 22 percent between 2014 and 2019, more than in any other racial or ethnic group.

For Democrats, this was not how things were meant to go. Hispanics were supposed to be part of an “emerging Democratic majority” consisting of educated and non-white voters, whose growing numbers and Democratic lean were supposed to sound the death knell for conservative politics. The theory began to show cracks with the election of Donald Trump. A further blow was dealt in 2020, when Trump nearly won the Electoral College with a coalition that fused increases among minority voters with continued strength among working-class whites. Both of the “emerging majority” theory’s originators, John Judis and Ruy Teixeira, have recanted it, with Teixeira becoming a fierce critic of his party’s fixation on identity politics.

One of the myths that came under scrutiny was that Hispanics could be treated as “voters of color,” a naturally Democratic group like African Americans, who would vote based on group solidarity. The left’s ill-conceived focus on skin color ignored the fact that Hispanics always had more in common with nineteenth-century European immigrants than with Blacks. Like white Catholics, Hispanics chose to come to America, thinking they might build a better life here. Blacks came here enslaved and lived under a regime of legalized oppression, bonding them together. Hispanics have also come to the United States from a panoply of different countries with about as much in common as Portugal and Poland.

In fact, the most common way that Hispanics in America identify themselves is not as Hispanic or Latino, or as members of a specific nationality, but as Americans. Polling my firm helped conduct among Texas Hispanics for Texas Latino Conservatives found them predominantly identifying as “American,” with nearly twice as many responses as the second most popular answer, “Texan.” “Hispanic” or “Latino” ran a distant third. Teixeira has also highlighted polling from the Voter Study Group that reveals that Hispanics would rather be citizens of the United States than any other country by a three-to-one margin.

Elements of both the left and the right have gotten Hispanics wrong at a fundamental level. They are neither an oppressed minority ready to be activated for a progressive agenda, nor third-world subversives ready to undermine the country’s Western heritage and traditions. They are something far less exotic: normal Americans. Just like the normal Americans of generations past who hailed from foreign lands, they eventually became recognized as members in good standing of the American mainstream and began voting like other Americans did.

Most explanations for the shift in the Hispanic vote have overemphasized tactical factors or issues specific to the 2020 election, like the specter of socialism or the issue of defunding the police. If socialism had been a decisive concern, the rightward shift would have been stronger in heavily Cuban and Venezuelan South Florida than it was in the Rio Grande Valley, where the population is Mexican or native to the region — but the shift was just as clear along the Rio Grande.

Both precinct and polling data from 2020 reveal a deeper realignment in most immigrant-heavy neighborhoods. Ideology seems to have played a role: Among non-white voting blocs, there is a significant mismatch between voter ideology and candidate choice; conservative nonwhites tend to support the Democratic candidate far more often than conservative whites. That mismatch shrank in 2020, as conservative nonwhites in every racial group swung towards Trump by a net margin of at least twenty-five points. There’s every reason to expect the ideological polarization will continue.

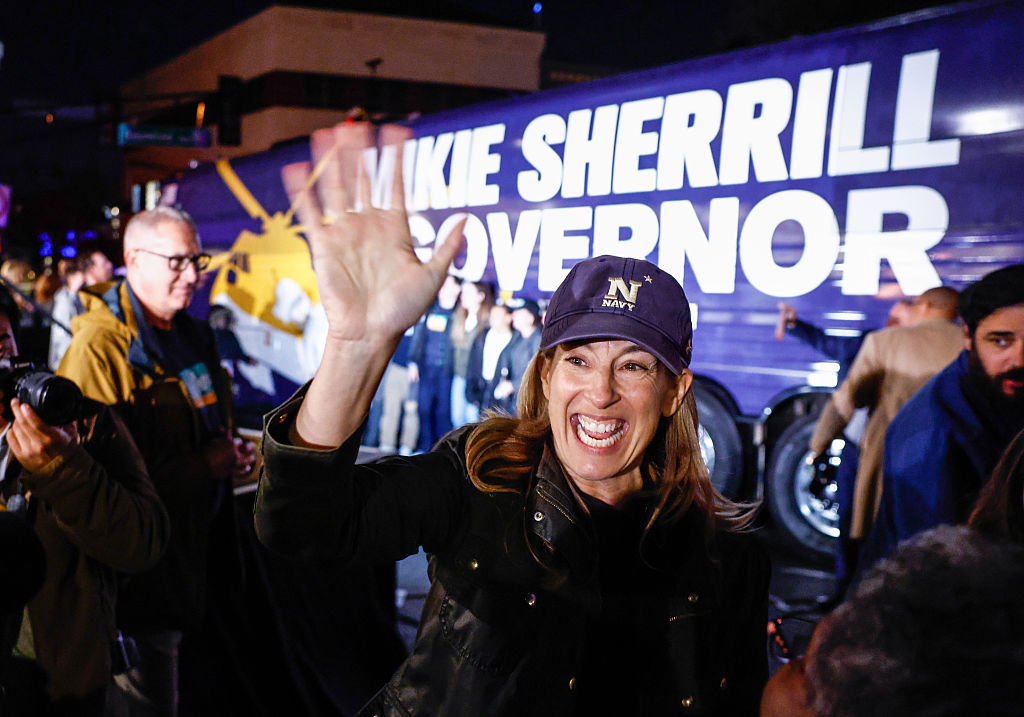

In November, the Rio Grande Valley will be a test case of whether this shift will stick. This June, Mayra Flores became the first Republican in more than a century to win a congressional seat there. She is defending it under more Democratic lines, and polls show her to be competitive. Flores is part of a trio of Latina Republicans — Monica de la Cruz in the 15th district next door and Cassy Garcia in the Laredo-based 28th district — who could make the Valley solid red in the next Congress.

In the Valley, the value of hard work seems to be a catalyst for the rightward shift among Hispanics. The idea that the Democrats “[support] government welfare handouts for people who don’t work” is what Hispanics have said they most dislike about the party, more so in the Valley, where voters were also likely to raise economic rationales for moving towards the Republican Party. “Hard work” was more readily associated with Republicans than Democrats by a fifteen-point margin.

The left has also lost the plot on border security, falsely assuming that Hispanics are activists for open borders. By a two-to-one margin — more in the Rio Grande Valley, Texas Hispanics choose stronger border security over letting in more asylum-seekers. The border patrol is a top employer in the region, and illegal migration is seen as an unwelcome incursion that makes their own neighborhoods less safe.

It is too soon to tell if Republicans will be successful in riding economic themes and border security to victory in the Valley’s three Congressional seats. Right now, they are favored in one — de la Cruz’s 15th — while the others are uphill fights against longtime Democratic incumbents. But even coming close would signal a durable shift among Hispanic voters in a region where Democratic incumbents were winning by more than twenty points in 2016. In either event, the long-term trajectory of Hispanics seems clear.

It might be a cliché to say that Hispanics only want what other Americans want. Of course, all groups differ from the norm to some extent. But the idea that Hispanics are fundamentally different from average Americans — resembling something closer to African Americans, with immigration as the new civil rights — led Democrats badly astray.

Like the ethnic whites of yesteryear, the predominant desire of Hispanics — and all immigrant groups — is to be more like other Americans, starting with the decision to depart their homelands in the first place. Being more like the rest of America has meant voting more like it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2022 World edition.