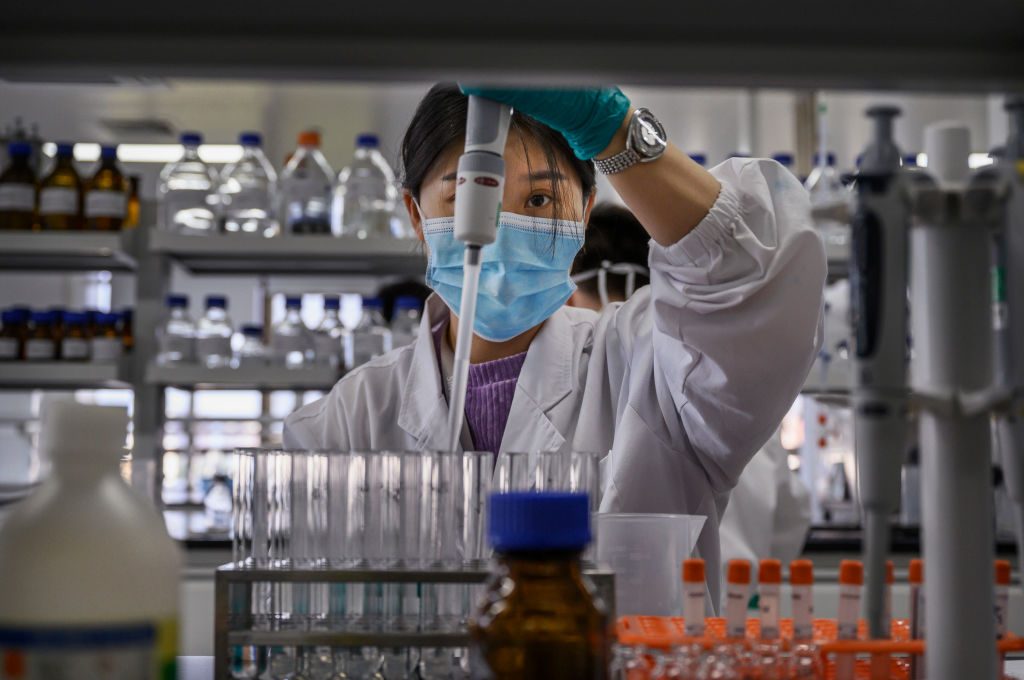

Back in May I wrote about a study by La Jolla Institute for Immunology, which raised the possibility that exposure to coronaviruses which cause the common cold could offer some degree of immunity to COVID-19. Scientists involved in the research had discovered a reaction to SARS-CoV-2 — the virus which causes COVID-19 — in the T cells of people who had not been infected with the virus, but at the time they weren’t sure whether it was a strong enough reaction to offer any effective immunity.

Since then, however, more and more evidence has emerged of T cell immune responses against SARS-CoV-2 which have been provoked by exposure to other coronaviruses, such as the common cold. The state of the science has been written up in this week’s BMJ by the journal’s associate editor Peter Doshi.

Several studies have confirmed the La Jolla results. The La Jolla team has now published its findings, revealing that blood specimens taken from patients between 2015 and 2018 — long before SARS-CoV-2 was known to exist – were found in 50 percent of cases to show some form of T cell response. In a German study, the T cells from 23 out of 68 of volunteers showed a T cell reaction to the virus, even though antibody tests suggested they had never been exposed to it. A Singapore study, too, revealed a T cell response in 12 out of 26 blood specimens taken before September 2019 — the earliest date at which SARS-CoV-2 is thought to have jumped from animal to human.

These studies are of immense importance because they bring into question a central assumption of the global response to COVID-19: that because SARS-CoV-2 is a novel coronavirus no one on Earth can have any immunity to it. It was on this basis, for example, that Professor Neil Ferguson and his Imperial College team predicted 500,000 deaths in the UK if no action was taken to suppress the virus.

The assumption made by him and others at the time was that herd immunity would not be reached in the general population until at least 60 percent of the population had been infected. If there is some degree of pre-existing immunity, however, that figure could be far lower — closer perhaps to the 23 percent who were found in New York to have antibodies, or the 20 percent found to have them in the Brazilian city of Manaus, where a seemingly runaway epidemic died back for no obvious reason.

***

Get a digital subscription to The Spectator.

Try a month free, then just $3.99 a month

***

The 60 percent herd immunity figure still defines most government thinking on COVID-19, and in particular whether or not to impose hugely expensive further lockdowns. Politicians might care to review the wider evidence on COVID-19 and immunity to satisfy themselves that they are making the right decision.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.