Bof! That useful French word — an older and slightly less irritating version of the American-English “meh” — is how many people feel about the re-election of Emmanuel Macron.

The center holds even as things fall apart — in twenty-first century France, anyway. It was inevitable and in the end easy. Mainstream commentators, almost unanimously pro-Macron, have spent the last few days trying to inject a sense of drama into today’s vote by suggesting the threat Le Pen posed was great. But it was painfully obvious that Macron would win. At forty-four, he will almost certainly still be president in 2027, when the constitution (as currently composed) will compel him to stand down.

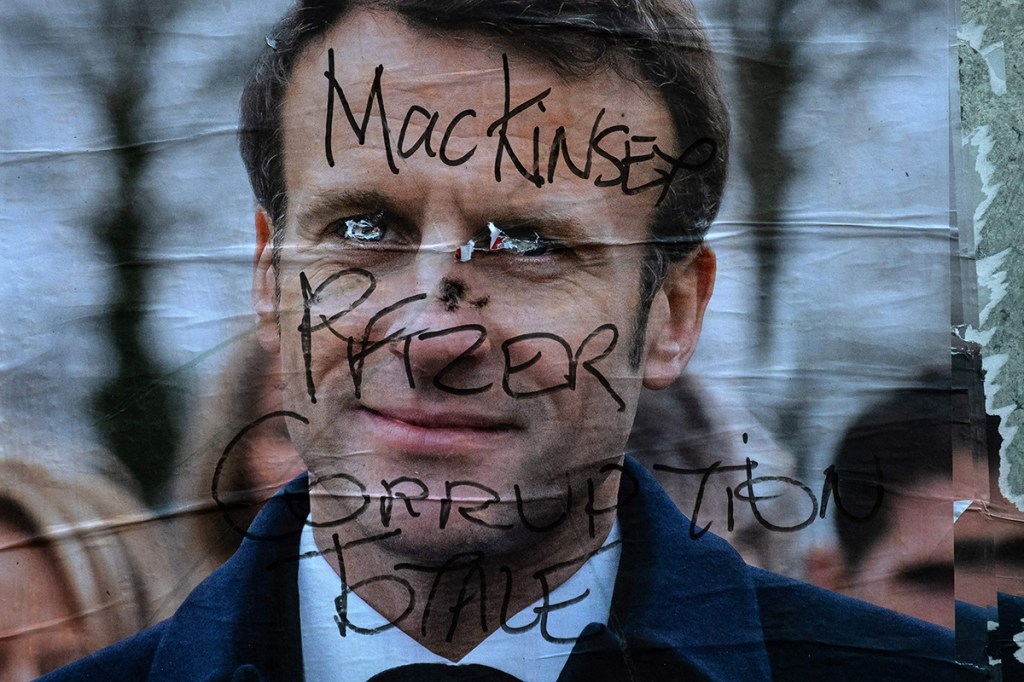

He isn’t loved. The abstention rate on Sunday is estimated to be 29.6 percent; up two percent on the second round of 2017. His job approval rating is around 41 percent, according to the latest surveys.

He is, however, more respected among the French, especially the elderly, than right-wingers in the Anglosphere tend to think. That fact is reflected in his impressive victory tonight. He projects confidence and competence even as his leadership does the opposite. That is useful in elections. He is arrogant and dislikable. He wasn’t sufficiently insupportable to make Marine Le Pen.

Le Pen did better in the debate on Wednesday night than expected. She also performed better in today’s second round; up from 33 percent in 2017 to more than 40 percent in 2022.

The “Front Republican” against l’extrême droite won again, but it is a diminishing force. Le Pen’s father only got 18 percent in 2002. Marine has expanded the appeal of her movement a long way. But not enough.

Will she keep plodding on to victory in 2027? Perhaps. But the real threat to France in 2027 could come from the radical left more than the right. Jean Luc Mélenchon far outperformed expectations two weeks ago by nearly reaching the second round ahead of Le Pen: he got almost 22 percent of the vote and came top among eighteen-to-twenty-four-year-olds.

Asked if he will run again in 2027, Mélenchon veered towards saying no: “I can tell you modestly that at this hour on this day, I do not believe that… I’ve worked with others and there is a very good team here that is capable of carrying on this fight and taking it on to victory.”

Mélenchon did say he wants to be prime minister, thinking he could force Macron into an uneasy alliance after winning more seats in the Assemblée Nationale elections, which begin on May 10. That’s an almost absurdly ambitious idea, but crazier things have happened.

Melénchon told his voters two weeks ago to hold their noses and support Macron. Only around 40 percent did, according to the latest polls. Thirteen percent went for Le Pen; 45 percent abstained.

Macron likes to feel he can read the political climate. It would be typically canny of him, having pivoted right in the build-up to this election, to go left in its aftermath. He’s an empty vessel ideologically, underneath all that chest hair.

The hope for conservatives is that, from the ashes of Valérie Pécresse’s terrible failure, the late collapse of Zemmour and the repeated losses of Le Pen, a new “l’union des droites” might rise triumphant. Until then, c’est Macron, bof.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.