‘Adrenochrome is a drug that the elites love,’ says gossip columnist-turned-conspiracy-theorist Liz Crokin. ‘It comes from children. The drug is extracted from the pituitary glands of tortured children. It’s sold on the black market. It’s the drug of the elites. It is their favorite drug. It is beyond evil. It is demonic. It is so sick.’

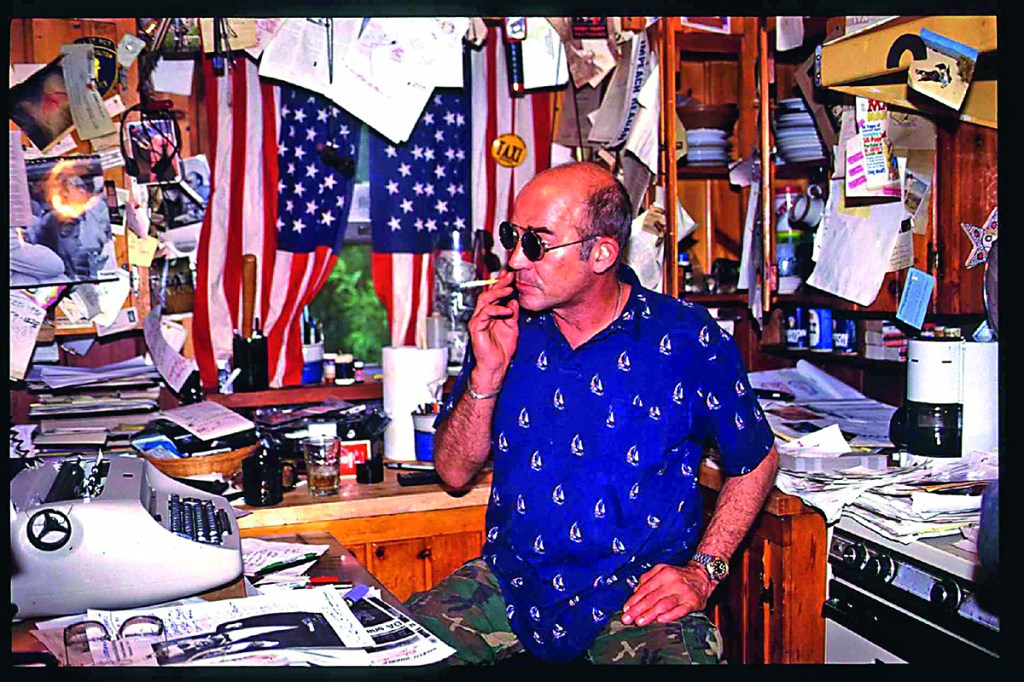

When I read this, I wondered where I had heard of adrenochrome before. Of course — Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, when Hunter S. Thompson is given a taste of the drug by his half-mad attorney:

‘“Where’d you get this?” I asked. “You can’t buy it.” “Never mind,” he said. “It’s absolutely pure.” I shook my head sadly. “What kind of monster client have you picked up this time? There’s only one source for this stuff.” He nodded. “The adrenaline glands of a living human body,” I said. “It’s no good if you get it out of a corpse.”’

This passage bubbled beneath the surface of American popular culture for decades. In 2009, Mark Dice, who is Alex Jones without the charm, referred to it in The Illuminati: Facts & Fiction, which implied that Thompson was some kind of Satanist pedophile. Adrenochrome also featured in the bizarre Matrix series — the esoteric books, not the films starring Keanu Reeves — as the preferred snack of extraterrestrials.

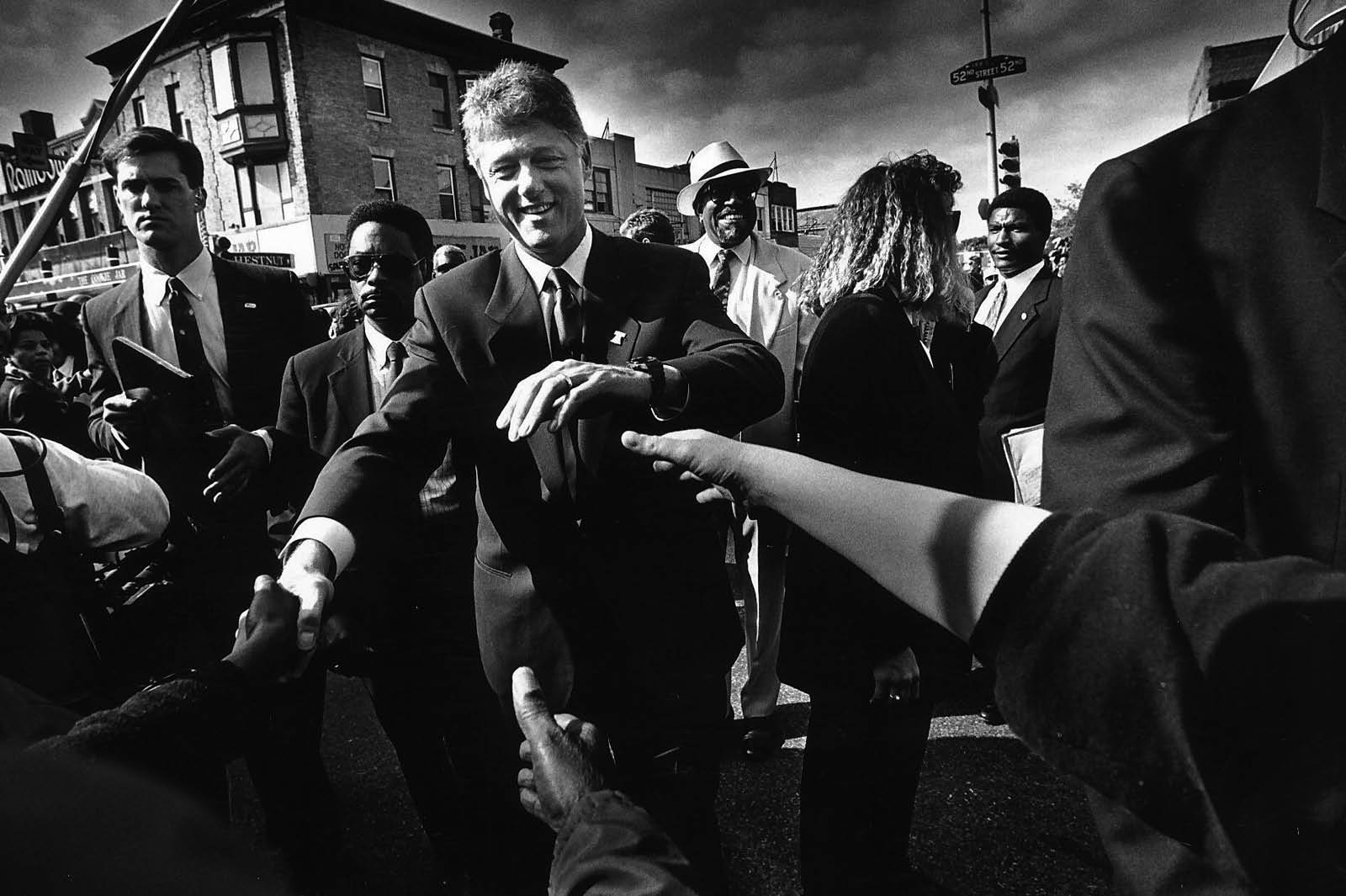

In 2018, rumors spread online that a video was circulating on the dark web showing Hillary Clinton and her staffer Huma Abedin mutilating a girl in order to harvest adrenochrome from her terrified body. No such video ever came to light, of course, but a meme had taken hold. Remember Pizzagate? Fervid elements of Donald Trump’s base convinced themselves that leaked emails between Democratic operatives contained some kind of code for the operations of an elite child-abuse ring centered on a DC pizza restaurant. The idea convinced one man to fire a gun in the restaurant and another to attempt to burn it down.

These fringe Trumpers have convinced themselves that the President is fighting an elite cabal of pedophiles and the ‘deep state’ apparatus that protects them. A purported insider named ‘Q’ has left cryptic posts on the message board 4Chan that detail Trump’s alleged plans for an event called ‘the Storm’ in which hundreds of his depraved opponents will be arrested. Somehow President Trump has never got around to doing this after more than three years in office.

The epithet ‘the Storm’ is derived from the time Trump informed the White House press pool in 2017 that he was ‘the calm before the storm’. The statement baffled journalists at the time, though Trump later expanded by saying ‘I am the storm.’ I think the simplest explanation is that he was running his mouth, not dropping occult references to some kind of millenarian apocalypse.

We must remember that secretive elite sex criminals do exist. There was Jeffrey Epstein and his international exploitative enterprises. There was Ed Buck, the wealthy Democrat donor, with his bizarre fondness for injecting black men with crystal meth. There were the Hollywood pedos exposed in the film An Open Secret. There were depraved men as diverse as Michael Jackson and Marcial Maciel, the Mexican priest who founded the Legion of Christ.

So there is nothing wrong with theorizing about elite sex criminals per se. But theories about elite sex criminality tend to inflate its scale and organization while defying epistemic standards. For example, when celebrities started being diagnosed with coronavirus, a reasonable person might have concluded that this was predictable: they do a lot of traveling and hand-shaking and have above-average access to testing. Not the QAnon crowd, though. They thought quarantined celebrities were being secretly arrested. Their excitement was dampened when Tom Hanks left his quarantine in Australia and returned to LA, but they soon devised a theory that the pilots of his plane were actually federal agents.

The role of adrenochrome in recent events is harder to fathom. Ms Crokin modishly suggests that pro-Trump patriots have ‘tainted the adrenochrome supply with the coronavirus’. Tommy G, the QAnon-supporting, Twitter blue-tick- sporting host of the No Mercy Podcast, posits that drug-crazed celebrities are ‘running out’ of adrenochrome. A depleted adrenochrome stash, Mr G suspects, might explain why Madonna has been making weird videos about roses and fried fish. The diminishing number of rational observers, I think, assume it is because Madonna is an attention-starved eccentric with no taste.

QAnoners are also big fans of comparing flattering and unflattering photos of celebrities. This is supposed to illustrate the devastating effects of adrenochrome withdrawal, but instead it illustrates the aging process and the possibility that people look different without make-up and an expensive hairdo.

The broader adrenochrome theory is based on two strange ideas. One, which is ubiquitous in QAnon circles, is that 800,000 kids go missing every year in the US. This is true but misleading. More than 99 percent of these children are reported missing but found. Of course, even one permanent disappearance is a tragedy. But this is not quite the startling statistic the QAnon crowd imagines.

The idea of extracting adrenochrome from a living body comes not from science or history but, as mentioned before, from Hunter S. Thompson. Given that Thompson created the literary form ‘gonzo journalism’, which explicitly prioritizes atmosphere and emotion over facts, trying to do this seems inadvisable. In fact, just as you can create testosterone without extracting it from the testicles or ovaries, you can synthesize adrenochrome in a lab.

Opinions are mixed on its psychoactive properties. In the 1960s, Abram Hoffer suggested that adrenochrome was a neurotoxic and might account for schizophrenia. True or not, I am not sure that a drug which makes you feel ‘changes in thinking…similar to those observed in schizophrenia’ would be such an attractive one, especially among people whose drug of choice is generally cocaine. I wanted to try it out myself, of course, but ran into objections from The Spectator’s lawyers and accountants.

Adrenochrome fascinates the QAnoners less as a drug than for its role in ritual: drug-crazed Luciferian elites sacrificing young children on an altar. Any aspect of this nightmare would be horrifying, but never so memorably as when child abuse, drugs, Satanism and secret societies are mixed together. In this aspect, the fantasies of QAnon are little more than an online echo of the Sixties counterculture at its most depraved.

The idea of Satanic ritual abuse, a bundling of everything awful in the psychological shadows, is not new. Tearing like wildfire through the 1980s, it led to appalling miscarriages of justice like the McMartin preschool case, in which the hapless owners and employees of a daycare center in Manhattan Beach, California, were accused of being depraved Aleister Crowley-like abusers. Satanic ritual abuse does occur — in 2010, a cult was discovered in Kidwelly, Wales, for example. But the imaginative power of the concept leads to exaggerated claims of its practice. And we might wonder whether the proliferation of false claims gives the actual practitioners a script for their depravities.

Americans are especially attracted to conspiracy theories. The ideas in Richard Hofstadter’s 1964 essay ‘The Paranoid Style in American Politics’ are widespread, but it is longer on examples than explanation. Feeling robbed of an Edenic home by a dark conspiracy might be more attractive to a nation young enough to be that idealistic, and whose origins included fantasies of malign ‘arbitrary power’ and ‘Popery’.

***

A print and digital subscription to The Spectator is just $7.99 a month

***

The conflict in American life between the folksy puritanism of the political mainstream and the obscure rituals of secret societies, private clubs and intelligence services opens up a dark and otherworldly space for paranoid speculation. Alex Jones could only have existed in America, inhabiting the spaces between Little League Baseball and the Bohemian Grove, between Mr Rogers and MKUltra.

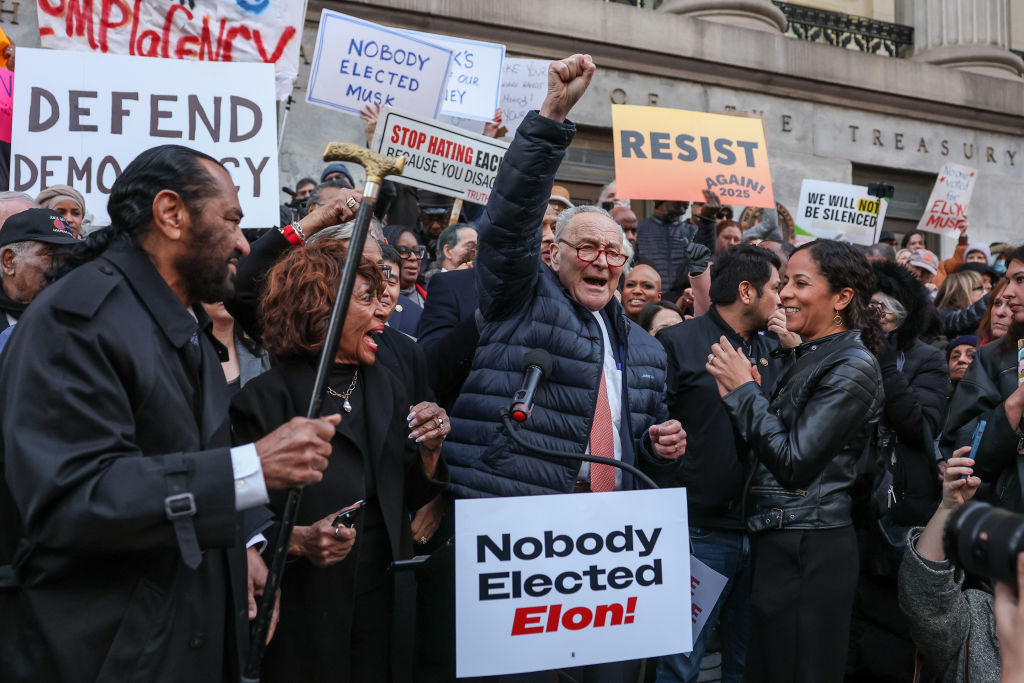

The presidency of Donald Trump has added a radical edge to the QAnoners. This is not due to extremism in his administration’s actions — but because of their moderation. He egged on chants of ‘lock her up’, but Hillary Clinton is still on Twitter insulting his policies. He encouraged ‘build that wall’ but the wall does not exist. A truly radical administration would contain radical followers. The increasingly dramatic and esoteric fantasies of Trump’s militant fringe are an attempt to rationalize the mundane reality.

I would like to suggest that there is hope for people who think Donald Trump has arrested Tom Hanks on charges of torturing children to harvest adrenochrome, but there is not. Their passions are so intense and their beliefs so elastic that if each claim were patiently disproven, they would twist the rest into newly preposterous shapes. The way to stop people from sliding down the long slope to fantasy is to teach them how to evaluate fact claims, to educate them about historical contexts, and also to encourage a vital sense of comic absurdity

This article is in The Spectator’s May 2020 US edition. Subscribe here to get yours.