COVID-19 is here to stay. Whether it flickers in wait or rages like wildfire, it will remain part of our lives for the foreseeable future. As the vast majority of people who contract the SARS COV-2 virus recover after mild flu-like symptoms then, the onus should be on finding ways to reduce the mortality in the minority who suffer the worst, rather than keeping society as a whole under draconian restrictions. Anti-virals and anti-inflammatories are potential strategies for this.

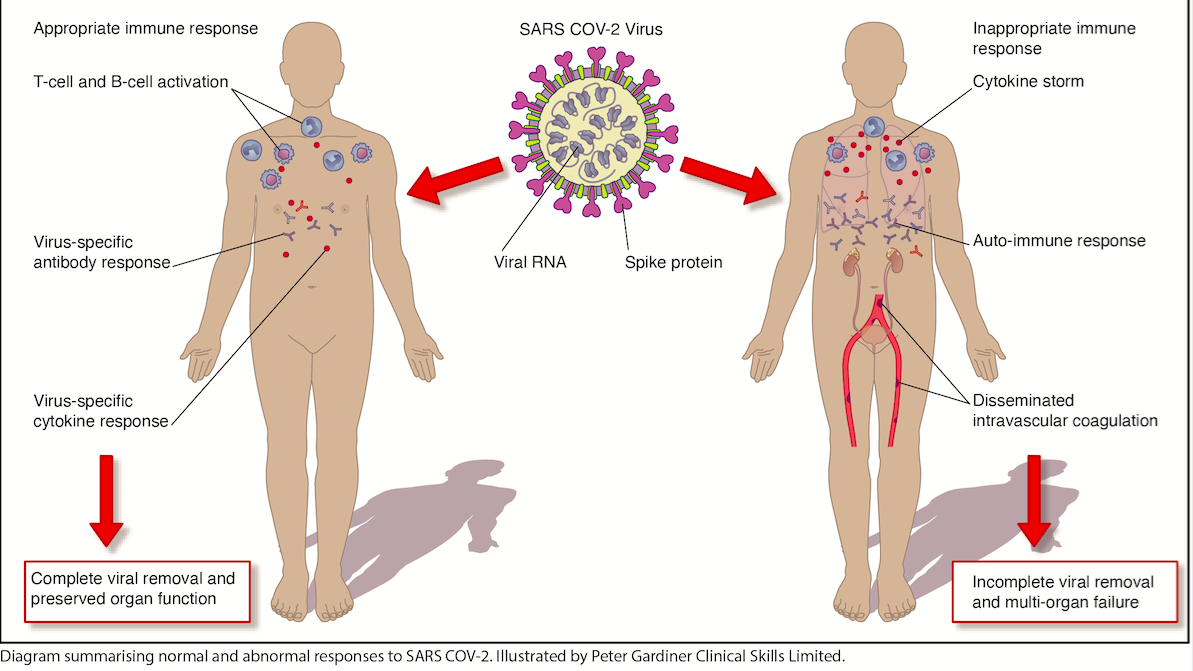

Death from the virus is invariably due to the direct damage it causes in the lungs or from the intense inflammatory response leading to multi-organ failure:

The lung damage occurs when the virus’s spike protein binds to our lungs, allowing it to enter and release its genetic material (RNA). Anti-virals can stop this process.

Hydroxychloroquine, historically used as an anti-malarial drug has been exploited recently for its anti-viral properties. It works by blocking the virus’s spike protein binding to our lungs. A clinical study in France demonstrated improvements in symptoms of COVID-19 patients taking hydroxychloroquine which led to its widespread use in the country. However, a subsequent UK randomized controlled trial (RCT) has shown no significant improvement in hospitalized COVID-19 patients taking the drug (RCTs, comparing the investigative drug to a placebo, are considered the gold standard in medical research due to their superiority in eliminating bias).

Controversy has often followed hydroxychloroquine, particularly after its promotion by Donald Trump and skepticism by his opponents, politicizing the scientific debate. A paper published in the Lancet in May stirred this hornet’s nest by suggesting that the drug increased the mortality risk in COVID-19 patients taking it. The paper was later retracted after external investigations found the data to be unreliable. However the damage from its publication had already been done, with countries such as France removing approval of hydroxychloroquine use in COVID-19 patients.

Perhaps a less controversial anti-viral is Remdesivir which has been established for many years in the treatment of Ebola. Remdesivir works by preventing viral RNA replication, terminating viral spread. A multi-national RCT has shown that the drug significantly speeds up recovery in hospitalized COVID-19 patients and the results have led to its approval in USA and Japan.

If anti-virals show some promise in treating those worst hit by coronavirus, what about anti-inflammatories? Inflammation is essentially the hostile environment created by the body in response to an injury or infection. It is what causes our body temperature to rise or our tissues to swell. It allows co-ordination of the adaptive immune response including the B-cells and T-cells that produce antibodies to the virus. Inflammation is mediated by tiny messengers called cytokines.

But for reasons currently unknown, these cytokines become over-active in certain patients with COVID-19 creating the so-called ‘cytokine storm’. During the storm, cytokines mediate inflammation in other organs besides the infected lungs and trigger detrimental pathways including the formation of blood clots called ‘disseminated intravascular coagulation’ leading to multi-organ damage and subsequent failure.

Anti-inflammatory drugs that can calm the cytokine storm include steroids. Naturally occurring steroids produced by our adrenal glands come in three varieties: (a) glucocorticoids controlling the immune-inflammatory system (b) mineralocorticoids controlling the body’s salt concentrations and (c) sex steroids controlling gender-specific physiology. Artificial glucocorticoids include dexamethasone, prednisolone and hydrocortisone which are prescribed for a wide variety of inflammatory and auto-immune disorders such as arthritis and asthma.

Glucocorticoids work by inhibiting the production of cytokines. It is a double-edged sword as this reduces inflammation but also makes the immune system weaker, rendering our bodies more susceptible to infection. What’s more, long-term steroid use carries significant side-effects including diabetes, bone weakening, skin thinning and psychological problems.

***

Get a print and digital subscription to The Spectator.

Try a month free, then just $7.99 a month

***

RCTs of Glucocorticoids used in patients admitted with cytokine storms to intensive care have shown significant improvements in hospital survival in non-infective and bacterial infective inflammatory causes. However, in viral infective causes of inflammation, such as influenza, there is some evidence that glucocorticoids actually make things worse.

It is this latter data that makes doctors uneasy about treating severely unwell COVID-19 patients with steroids. However, an RCT investigating the effect of dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 requiring respiratory support, demonstrated that there was a substantial reduction in the risk of death in those taking dexamethasone compared to those who did not. Interestingly, they found that in patients requiring no respiratory support, steroids made little difference. The results give an insight into how we can strategically use steroids by prescribing it in those who are significantly compromised rather than in those with an appropriate immune response.

While these drugs might not be perfect, they offer us hope in extracting ourselves from our current predicament. Seeing our children separated in chalked-out school playgrounds, or young adults committing suicide during lockdowns, or people suffering with treatable conditions at home when hospital beds remain empty are things that can never be justified in this inverted-utilitarian society. We have drugs that can potentially be used to treat the minority who experience the worst from the virus, but we must accept that we cannot save everyone. Should future waves of this virus or a novel virus emerge, we must study its effects scientifically in real-time, rather than use predictions made on impetuous models, so that we can employ more targeted medical and public health strategies based on reality and not fear.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.