Basking as it does in the glow of many charms, from its climate to its culture, Brazil has long projected an enchanting image to the world. But two years after a presidential impeachment that many still see as a soft coup, and against a background of rampant corruption and violence, polar opposites are tearing into each other as Brazilians prepare to go to the polls, poisoning the atmosphere in a usually cordial country and testing the foundations of democracy in a pillar of the West.

With its emotional fissures and dissatisfaction with politics as usual, this election campaign is a microcosm of many of the challenges that currently bedevil liberal democracies around the world. True to Brazil’s form for linguistic inventiveness, many people now perceive an angry split between right-leaning coxinhas and leftist mortadelas, a vivid food metaphor that rivals the mutual incomprehension of snowflakes and the alt-right in Trump’s America, and talk of gammons in Brexit Britain’s divided demos.

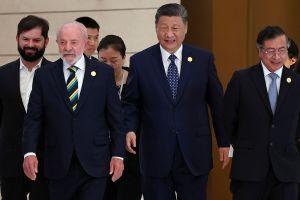

Loved and loathed, the leftist former president Lula continues to cast a great shadow, holding court from jail after a corruption conviction that even some of his fiercest opponents have questioned. His fans adore him for alleviating poverty and symbolising an era of optimism, while his detractors see his years in office as a period of corrupt misrule. For as long as possible, Lula’s Workers’ Party — the PT — maintained the pretence that the former metalworker would be on the ballot on October 7, keeping his millions of loyal voters fired up and giving him a big lead in the polls. But a ruling from Brazil’s top electoral court forced the charade to an end, and on September 11 the PT anointed its second-choice candidate, Fernando Haddad. The party’s new slogan assures voters that ‘Haddad is Lula’, and polls have shown that the strategy has started to pay off.

The other main shadow hanging over the election is that of Jair Bolsonaro, a controversy-courting former soldier, who recently sustained a stab wound while out campaigning and has been recovering in hospital. His rough manners and promises to shoot gangsters and sweep away corruption appeal to a broad base of hacked-off citizens, and polls have consistently predicted that he will make it handily into a runoff on October 28. Bolsonaro’s rhetoric has included saying he would beat a gay couple kissing in public, and that a female politician wasn’t worth raping. His unconventional approach and attention-grabbing antics — delighting his fans and winding up his enemies — have fuelled talk of him being a kind of Brazilian Donald Trump. Many urbane Brazilians have been shocked to see old friends backing him on social media, which has become a poisoned agora in which people on all sides have been slamming shut the window of friendship and storming off to coddle their alternative versions of the truth.

In his 1976 hit ‘Meu caro amigo’, the Brazilian musician Chico Buarque sang out a letter to a friend in exile, telling him that although rain still followed shine and there was plenty of samba and football, life under Brazil’s military dictatorship was dark. But in today’s Brazil, even the national sport has become a faction-ridden battleground. When the Tottenham Hotspur star Lucas Moura backed Bolsonaro on Twitter recently, the explosive reaction provided a fresh example of the hard feelings on either side of the debate. Meanwhile, many left-leaning Brazilians feel that the use of the national football strip at pro-impeachment demonstrations has sullied a once unifying symbol.

Lula’s hand-picked successor Dilma Rousseff — the first woman to wear the presidential sash — narrowly won a fourth consecutive term for the PT in 2014. But in 2016, a successful campaign to impeach her handed the presidency to her running mate, Michel Temer, who is from another party. The atmosphere became tetchier still as a corruption investigation steadily uncovered a web of graft running all the way to the top of politics. The PT’s opponents sought to blame it for all the corruption, but Rousseff’s erstwhile voters are bitterly angry at what they see as an annulment of popular sovereignty — a potential warning for people in Britain who dream of overturning Brexit.

As in many other Western democracies, the emotional extremes of Brazilian politics have been crowding out the centre. A more traditional candidate like Geraldo Alckmin — a former doctor and four-time state governor of São Paulo — has so far struggled to impose himself, despite his plum allocation of public airtime and his centre-right party’s past tendency to get its candidates into the second round. And while the softly-spoken environmentalist Marina Silva, who grew up tapping rubber deep in the Amazon, has slipped in the polls, the professorial but hot-headed leftist Ciro Gomes looks like he’s in with a shout.

If Bolsonaro and Haddad do end up going head to head in the second round, the clash will get even more polarising and divisive. On one side will be a far-right candidate who has praised the dictatorship that ruled Brazil until 1985. On the other will be Lula’s surrogate, whose new running mate is a communist. It is also the least predictable scenario, with Bolsonaro and Haddad currently polling neck and neck in a runoff. Victory for either side would leave the other in despair, not to mention the millions of more centrist-minded Brazilians with no-one to vote for. There is also the prospect of a victorious Haddad trying to free Lula, and some Brazilians even worry what the Army might do if it doesn’t like the outcome. Its commander raised eyebrows in April ahead of a court ruling on Lula’s case by tweeting that the Army ‘repudiates impunity’.

It may well take pressure to make diamonds, but there is also a feeling that Brazil’s rapaciously dysfunctional politics are holding the country back culturally as well as politically, as shown by widespread anger over the fire that recently destroyed countless treasures at the country’s national museum in Rio. Once a royal palace, the building had been operating on a shoestring. Brazil’s economy, the ninth largest in the world, is in a similar position. Political uncertainty has weighed on its performance, and the bickering and corruption stand in the way of building much-needed infrastructure.

When Lula took over in 2003, the spectacle of an orderly transition between stark rivals less than 20 years after the end of military rule nourished a new optimism. But now, after two years of a president the people didn’t choose and with post-truth factions berating each other, the country’s young democracy — and with it the broader Western model — faces a major new test.