The usualness, you might say, of the late Bob Dole is what would render him highly, and commendably, unusual in today’s politics.

He was no Reagan or Taft, and certainly no Madison. He had no grand vision he wished to implement in public life. But he had judgment and common sense. He lacked entirely the dubious gift for making long-term enemies. His patriotism — his love of the land he served and fought for, with lieutenant’s bars on his GI helmet — was deeply embedded.

Most conspicuously, he had guts and determination. He was up for any contest that involved the preservation of his convictions and ideals — including the lifelong contest he waged against the agony of a partly destroyed physical body. Bob Dole willed himself to recover insofar as possible from the shrapnel and gunfire wounds that might have killed him as he led his soldiers in Italy through a mine-strewn battlefield.

None of which is to say that guts and patriotism are outsider commodities in the politics of the 2020s. It is to say that guts and patriotism seem more seldom than in Dole’s time to arouse emulation and admiration. Our political leaders appear to think their main modern task is passing out favors and benefits paid for by undeserving and over-rewarded “others.” Lately another task has emerged — that of lamenting, bewailing and apologizing for the apparent sins of Americans celebrated at one time for bringing a new country and culture into being.

Bob Dole, we have to assume, wouldn’t go anywhere on the present political scene. He didn’t get the idea that America was about something other than freedom, opportunity and duty.

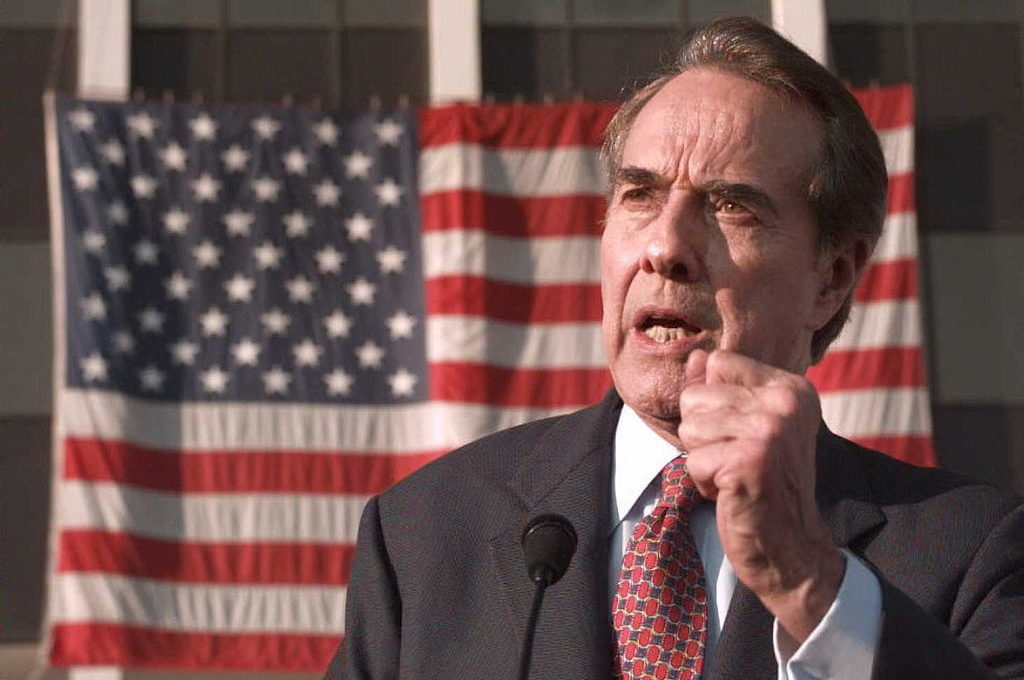

As congressman and senator from middle-of-America Kansas, as vice presidential and presidential candidate, Dole was a sort of happy warrior. He enjoyed standing up for what might broadly be described as American values. He loved America. The wounds he received in her defense were, as he saw it, scribbled on the price tag for human liberty. His long convalescence — in earlier wars, he would have died of similar injuries — was the central experience of his life, leading to all that followed. And why not? It showed what he was made of.

Lieutenant Dole lost the use of his right arm. Merely dressing in the morning — a thing most of us do without reflection — was for him an ordeal. I remember meeting him in the Seventies or Eighties. He carried in his dead right hand a pen or pencil. It was so you would know not to reach for that hand in greeting. You were to reach for the still-working left hand. How about that? The guy couldn’t shake hands in the normal fashion. It didn’t stop him.

Nothing stopped him, really, except bad timing with respect to his successful bid for the Republican presidential nomination. He ran against Bill and Hillary, to whose, ah, ways and modes the electorate had adjusted during a period of general satisfaction with things as they were. There was no stopping the Clinton machine. “It’s my turn,” Dole was known for having told Republican movers and shakers — as perhaps it truly was, considering his tenure and tireless work for the GOP. The loss, in 1996, expelled him from the active practice of politics without slaking his enjoyment of that for which politics, and physical suffering, had fitted him — namely, speaking out; extolling; faulting; affirming; defending, with no special hope of profit from the exercise. Of the time left to him, he spent much in the promotion of continued or renewed honor for American vets — the sort he himself had led in combat.

Dole, a middle-American conservative from rural Kansas, occasionally vexed exponents of conservative orthodoxy or strategy. He was never going to please everyone and seemed unwilling to try. The broad principles he espoused came less frequently from books and seminars than from the beating heart of his country.

In defense of these principles he employed a much-remarked-on wit that was his very own: sharp and acerbic. He loved getting down to cases: reducing intellectual complexities to straightforward pronouncements, such as inquiring, during the vice presidential debate in 1976, say, who were these Democrats, with their gift for getting America into wars — who were they anyway, to be calling Republicans warmongers? It didn’t go over with everybody. Politics was already moving off its old pivots. But many of us smiled and laughed all the same. Hey, Bob! — that was telling ’em, sure enough.