Considering how likely we all are to be blown to pieces by it within the next five years, the atomic bomb has not roused so much discussion as might have been expected,” wrote George Orwell in 1945.

The public conversation soon caught up with the lethal realities of the nuclear age. The possibility of annihilation loomed over politics, domestic and foreign, for much of the second half of the twentieth century. Then, with the fall of the Berlin Wall, it faded into the background. Thanks to Vladimir Putin, the threat has returned to the fore.

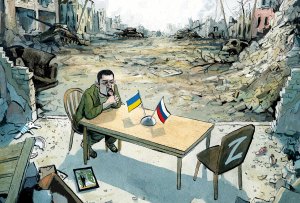

The isolated and unpredictable strongman in the Kremlin is not shy when it comes to reminding the world of Russia’s nuclear arsenal. If anyone “tries to stand in our way,” Putin warned on the eve of the invasion of Ukraine, they would face “consequences with such as you have never seen in your entire history.” The returning possibility of nuclear war may be just one of the ways in which Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has brought our holiday from history to an abrupt end. But it’s the most alarming.

Into this tense standoff steps Joe Biden, seemingly convinced that he is the man for this fraught moment even as he demonstrates otherwise with nearly every public utterance. On a recent trip to Europe, the most important diplomatic mission of his presidency, he could barely open his mouth without issuing a foolhardy provocation. He threatened regime change in Moscow, implied that American troops were about to be sent into Ukraine and suggested the United States would respond “in kind” to a Russian use of chemical weapons.

These statements were widely labeled “gaffes.” To be sure, they were the misstatements of an aging politician not known for his rhetorical dexterity. But they also revealed hotheadedness, ill-discipline and self-righteousness: traits that were identifiable even in a younger, more alert Biden — and traits that now make the world a more dangerous place.

“The adults are in charge again,” bragged Biden’s advisors when they entered the White House. This claim of competence was soon disproved by events, but it also obscured a tension in Biden’s foreign policy. The president elected on a promise to restore America’s alliances has also shown a clear determination to pare back America’s global role. The withdrawal from Afghanistan highlighted that contradiction: a move built on a serious conviction of the need to acknowledge the limits of American power — that enraged our closest allies.

At the time, many foreign policy restrainers and realists welcomed a president who appeared to see the world the same way as they. But in Ukraine, the administration has stumbled into a strategy that pleases no one. The camp that saw the logic of the Afghanistan withdrawal, however botched its execution, may have welcomed Biden’s explicit ruling out of escalatory steps like a no-fly zone and his willingness to let Europeans take the lead in assisting Ukraine. But they cannot be comfortable with the administration’s drift toward regime change in Moscow as a US objective.

Biden’s public declaration that Putin “cannot remain in power” may have been a gaffe that was quickly walked back, but the policy steps the US president has taken suggest that the removal of his Russian counterpart is his ultimate goal. From ratcheting up sanctions to admonishing Putin as a “war criminal” and a “thug,” these are not the steps of an administration putting de-escalation first.

Those who favor a bolder approach might agree with some of Biden’s rhetoric but find worryingly little action to back up the talk. That hazardous gap between rhetoric and policy isn’t limited to Ukraine. At a dangerous moment in history, Biden seemingly refuses to acknowledge the difficult choices and tough tradeoffs that lie ahead. This administration appears to think that Putin will be gone, Ukraine will be free, China will be contained, a deal will be reached with Iran that doesn’t give another regime a nuclear weapon and the US economy will fend off “Putin’s price rises.” Everything, in other words, will be just fine. And all without a meaningful change of course in US policy.

What makes that complacency even more dangerous is the self-congratulatory mood in the West, that marvels at the unity on display in response to Putin’s aggression. In truth, the anti-Russia coalition is far from universal: few non-Western nations have altered their economic relationship with Russia since the conflict began; important allies like India have been reluctant to take a side.

Given the inconsistency of this administration’s foreign policy, this dangerous cocktail of escalatory rhetoric, hubristic self-importance and a dearth of strategic thinking may be the closest thing we get to a “Biden doctrine.” Whatever you call it, it is not a recipe for a safer world.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2022 World edition.