I am a dental basket case. When I was a child, my orthodontist used to joke that he could drive a Mack truck between my two front teeth. I didn’t have braces so much as fight a losing battle against the evil telekinetic forces at work in my mouth, which seemed to shift my molars and incisors around at will.

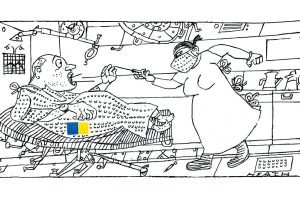

This was back in the 1990s when orthodontics was a matter of steel torture devices glued to your teeth — and I had all of them. There was the expander, a kind of bear trap in the roof of my mouth, which every night my mother would tighten by inserting and twisting a key. There was the headgear, the wires that circumnavigated half my head, which my orthodontist was delusional enough to think I was going to wear to school. And there were the braces themselves, metallic and sharp, though at least you could customize the colors of the rubber bands, decking out your teeth in autumnal warms or a nice pastel scheme.

I remember the day when my childhood orthodontic work ended. Twelve years of a medieval armory in my mouth somehow hadn’t brought my teeth to heel. An ashen-faced and visibly shaken orthodontist told me he’d done all he could, that I was on my own now. (He did suggest I get surgery but that would have involved breaking my jaw so I said no.) He also asked whether he could use photos of my teeth in a seminar he taught, presumably as a cautionary tale for anyone considering the orthodontics profession. I told him yes.

And then it was off to college and young adulthood, where I forgot all about the oral anarchy raging just past my lips. Twenty-something men care about few things less than dentistry, and I was no exception. It was only after I finally grew up (read: got married) that I got around to regularly seeing a dentist again. He politely observed that my teeth seemed to be descending into a Hobbesian war of all against all, and recommended a treatment, something called Invisalign. It was basically braces but with plastic liners instead of steel. No more looking like Jaws from Moonraker.

I turned him down at first. Then Covid struck, and I figured, why not? If I was going to be stuck at home, I might as well make an investment in my health.

Owing to an apparent case of amnesia, I thought my Invisalign regimen would be over rather quickly. My wife had blown through her liners in nine months, and I idiotically assumed I would be the same way. What followed was a two-year ordeal of clicking plastic trays in and out of my mouth. Invisalign is supposed to be, well, invisible, or at least barely noticeable, yet not only can you clearly see the liners on your teeth, mine had several bumps on the backs of them, near my tongue. That meant I lisped when I spoke. Badly.

As someone who spends a good part of his day participating in Zoom meetings, teaching writing classes, and hosting podcasts, this was less than ideal. It was enough to make anyone self-conscious, or shelf-conshiousth as I was now putting it. Then again maybe not: I once watched a friend teach a seminar with Invisaligners proudly in, hissing like a cobra the entire time. And surely our civilization has bigger things to worry about than yuppies rolling their S’s.

The problem is that to lose your voice, to hear yourself speak differently than you’re accustomed to — that’s enough to give most people pause. So it was that I got used to popping the things out when I’d speak in public, only to pop them back in afterwards. It was annoying, but I still wore them. Oh, I wore them. And my dentist seemed pleased with my progress. My jaw was coming into alignment for the first time in my life. I now knew what it was like to bite down and have my teeth match up the way they were supposed to.

Then, last summer, I hit a wall. I was about ninety-five percent of the way there, but my frontmost teeth wouldn’t quite clear that final slender gap. Also, for reasons unknown, the liners were suddenly turning my teeth yellow. My dentist is a wonderful and meticulous professional, to the point that I’m tempted to call him the Ben Carson of molars (though I live in deep-blue Northern Virginia so that could cause a rift). But he conceded, just as my prior orthodontist had, that he might have done all he could.

Ninety-five percent, I told him, was still an A. Mostly I was just ready to get the damned things off. So off they came, along with a badly needed polishing.

I know some will think it’s ironic that I’m writing about dental health in a publication with British roots, but I think the premium America places on teeth makes sense. A leading cause of death among the earliest humans was dental abscesses — wouldn’t we want to learn that lesson as much as possible? And given our present-day Zoom-and-selfie-based economy, isn’t it only natural that we’d want our mouths to look in order?

It feels good to smile again, in the American way, blinding anyone who looks at me directly. And surely now that I’m done with Invisalign, my oral forces of darkness have been banished forever…right? Anyway, I’m off to finish the last of the Halloween candy and wash it down with a mug of black coffee. Stay pearly, my friends.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2022 World edition.