There’s nothing like the sound of automobile engines at wide-open throttle, whirring by like a squadron of World War Two fighter jets in dive-bomb mode. But at the Lime Rock Park racetrack, the adrenaline-pumping hum is made even more riveting by the fact that you hear the overture of baritone bees before you see what’s making it.

Lime Rock is in northwest Connecticut, “between Boston and New York City and is easy to access from all points in the Northeast.” That’s what the website claims, though in my experience, no place between Boston and New York City is “easy to access.” The site is right, however, in saying, “An essential part of the Lime Rock Park experience is the journey here.” Over Labor Day weekend, after much traffic, I ventured through gentlemen’s farms, past quaint general stores and over the hilly, rural remnants of old Connecticut, now fenced in by new money.

I arrived for the fortieth annual Historic Festival, where $500 million worth of vintage cars show up. To enter the park, you cross a plank bridge that goes over the racetrack. You don’t realize how fast the cars are really going until they zoom underneath you and let them gust you with the faint fragrance of rich fuel, capturing a blurry photo of them on your phone.

I took a spin through the “German circle,” where masterfully restored and maintained BMWs and Porsches were parked to be peered into and admired. Their flawless paint jobs glimmered in the sun. Their windows were rolled down halfway, too, for better viewing of the analog dashboards (like fine timepieces), exquisite interiors (unblemished leather with contrast piping), and attention-to-detail knobs and gear shifts — all of them different and all of them works of art.

Part of the paddock was allocated to a “swap meet,” in which aficionados buy and sell and barter for no-longer-made vintage vehicle parts — OEM (original equipment manufacturer) headlights, hood ornaments, instrument clusters (speedometers and gauges), trim pieces, memorabilia, etc.

Then onto the more businesslike part of the paddock, where racecars and their drivers come and go from tents and trailers. I met up with Tom Donatelli, a banker by trade and racer when time and resources allow. Like a scene from the 1971 Steve McQueen film Le Mans, drivers and mechanics in half-zipped fire suits milled about talking shop. There was an energy and a tension here, as drivers prepared to take to the track, mechanics scurried to fine-tune or fix their cars, and elation and disappointment collided among drivers returning from their races.

I marveled as, in an age where such vehicles are increasingly becoming valuable investment pieces, people took their irreplaceable collectors’ items onto the track and drove them as they were designed to be driven. I tried not to let the soulless nature of modern car culture spoil the day, but the topic inevitably came up.

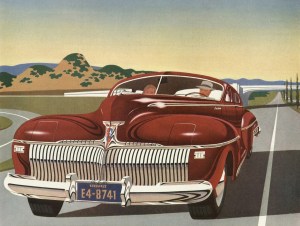

What people love about vintage cars, Tom said, is that they were “not designed for some bureaucrat.” When the historic cars racing at Lime Rock were made, “Cars represented freedom. Guys were coming back from World War Two and their families were earning disposable income and living the American dream, and cars were part of the dream. Cars were in movies. James Bond. Sophia Loren was driving an Alfa Romeo. There was a romance about cars.”

These days, “unless they’re utter gearheads,” young people “have little affinity for cars.” Teslas are in high demand because the current generation is enamored by the thought of a mobile media platform. Tom compared Teslas and the bulbous new Porsches to a 1971 Dino Ferrari. “The sound, the smell, the whole thing is a sensual experience,” he said. “The proportions are right, the lines, everything.”

With new cars and their rear torque vectoring, automatically deploying aerodynamics, stabilizing computers and so forth, “There’s no driving the thing! It’s like — do you want to go out with a girl, or do you want to go out with a soulless battery-operated mannequin? It’s the same thing!”

Tom introduced me to Glenn Taylor, a master mechanic and former Sports Car Club of America racing champion. Glenn raced against Michael Andretti in the early 1980s. He didn’t win.

“My sister was my crew. [Andretti] showed up with four racing mechanics, a driving instructor, and two cars. I’m living out of my van and he’s flying in and out in his helicopter.”

Glenn was reserved and quiet, and I wouldn’t have guessed he had experience at Sebring, Le Mans, all the major tracks really, had Tom not put him on the spot. Glenn lit up, though, when asked what the most catastrophic thing was he’d ever fixed.

“Oh! I can show you,” he said, pulling up a YouTube video on his phone. “Just Google, ‘Scott Sharp crash,’” he said.

Sharp, a professional driver, was uninjured, in the 2009 collision but his vehicle was a mangled mess. Glenn and his crewmates worked for twenty-two hours to rebuild the thing completely so Sharp could race in the main event a day and a half later. Glenn drove the repaired car from the pits to the paddock. “All the other teams came out,” he said. “All the crews, the spectators and everything. It was like Moses and the sea spreading and I’m driving. They were all clapping, and I almost started crying.”

Glenn blames the depressing homogenization of contemporary cars on “the government mostly. They want cars to have batteries. They’re fast, but they don’t have pistons.”

I take comfort in knowing these endangered species have a home at Lime Rock and a group of fun, gracious, die-hard vintage car enthusiasts as caretakers. One of them offered a helpful compromise, too. When he was forced to drive a Tesla recently, he despised the silence. So he used the infotainment system of the “iPhone on wheel” to fire up a recording of the Monaco Grand Prix.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2022 World edition.