The countries we call Anglo-Saxon (Great Britain, the Commonwealth and the United States) have been known for centuries for their ability to govern themselves democratically, peacefully and efficiently. In the twenty-first century they have been doing less well.

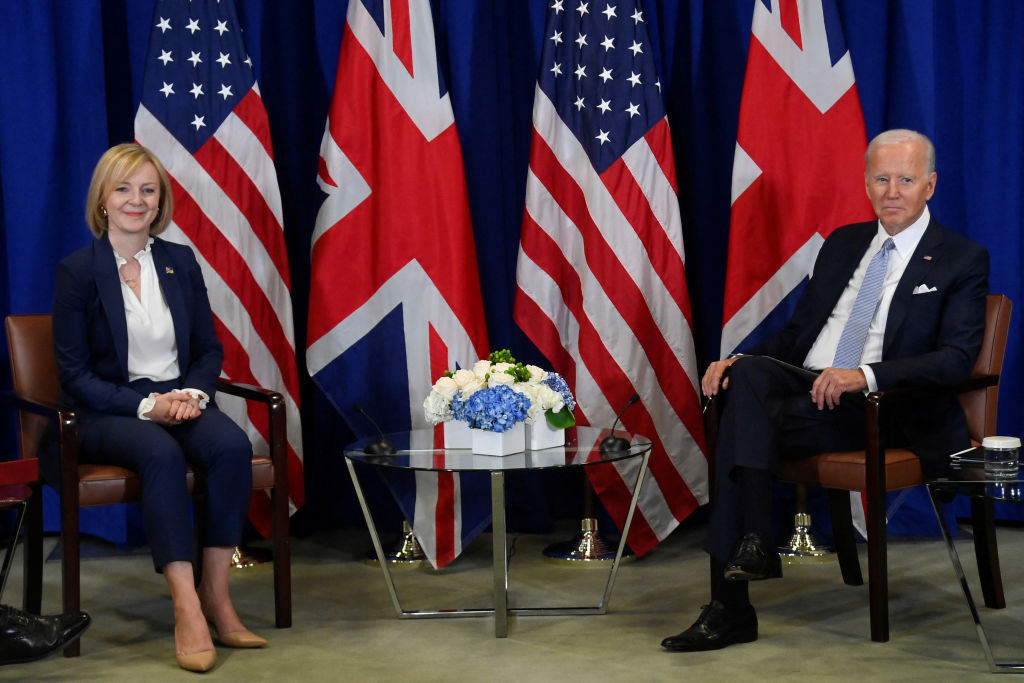

Britain and America are both in dreadful straits politically, economically and socially. The implosion of Boris Johnson and the search for a satisfactory successor have revealed the leadership of the Tory Party as a hapless and embarrassing collection of mediocrities devoid of coherent ideas. Across the Atlantic, one of the two major parties is a gerontocracy at the top and a gang of urban guerrillas with Molotov cocktails at its base. The other was exhausted as a coherent force by the end of the 1990s and has, for a full generation now, effectively been two parties, neither able to kick free of the other.

In the United States, as in Great Britain, the low quality of public officialdom has been plain for several decades. The level of public discussion and debate among politicians and the media is correspondingly shallow, jejune, semiliterate and vulgar.

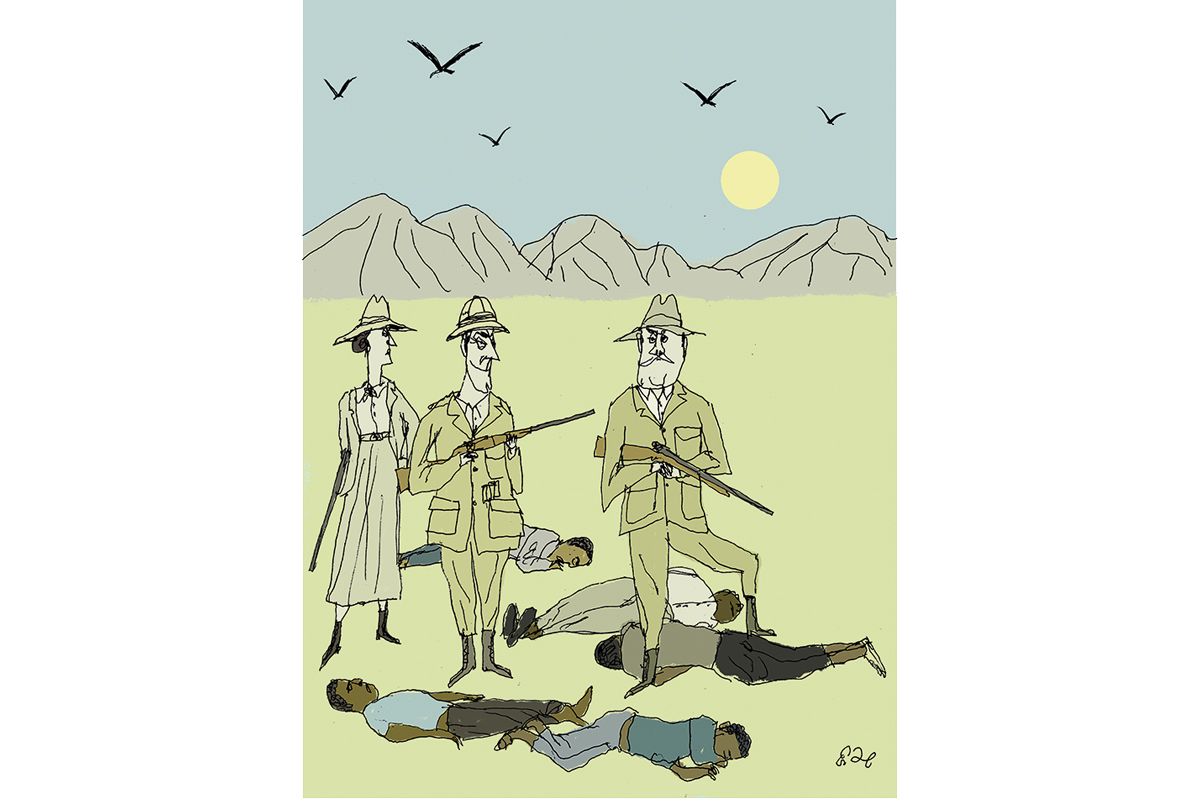

The situation is hardly unprecedented in the history of the Anglosphere. One thinks of the corporate banalities of the 1920s, the Marxist ones of the 1930s, and the cultural vapidities of the 1950s. But over the past quarter-century a new and distractive element has been introduced into Anglo-Saxon political culture. I say “distractive” because the proper business of politics in a democracy is politics as it is understood in a political democracy, not a social democracy: politics as it was practiced in the Anglo-Saxon countries before the Great War, when politicians understood government as national housekeeping and defense rather than as a project for mobilizing the whole of society in order to perfect it.

The distractions that have caused democratic politicians to shirk their proper responsibilities are matters in which they, at best, make mischief and, at worst, cause disaster by meddling in areas where government has neither constitutional mandate nor political competency. These include what politicians call “equity” between racial and ethnic groups; social “inclusiveness” among definable groups; relations between the sexes; public education (in America, properly a local and state responsibility in any case) and education at the college and university levels; the medical profession; local environmental policy; cultural affairs and innumerable other areas that government has invaded and where it has staked out a regulatory claim.

Though formally, at least, the United States and the United Kingdom remain constitutional democracies, the truth — resolutely ignored by their respective national governments — is that even formal democratic government does not agree with a socialist program, which makes democratic society a sham and democratic government both unworkable and fatally unaffordable. Further, a democracy that has degenerated into social democracy struggles to produce a people fit to govern itself.

Britain today is facing a comprehensive political, economic, technological, social, institutional, cultural and moral crisis for which the British people — as much as their elected politicians, their civil service and their managerial classes — are responsible. The same goes for the United States, though the crisis is less immediately acute here. A democratic people gets the government it deserves — and gets it good and hard, as Mencken said. Having once elected it, it can either throw the bums out — or suffer them. Decadent electorates succumb to the sweet nothings whispered, the false promises made and the luxuries lavished upon them by seductive politicians, and they continue to do so until the Treasury’s checks bounce. Socialism makes a doting and extravagant lover — and an absconding husband, his pockets stuffed with high-denomination banknotes and nothing in the bank account.

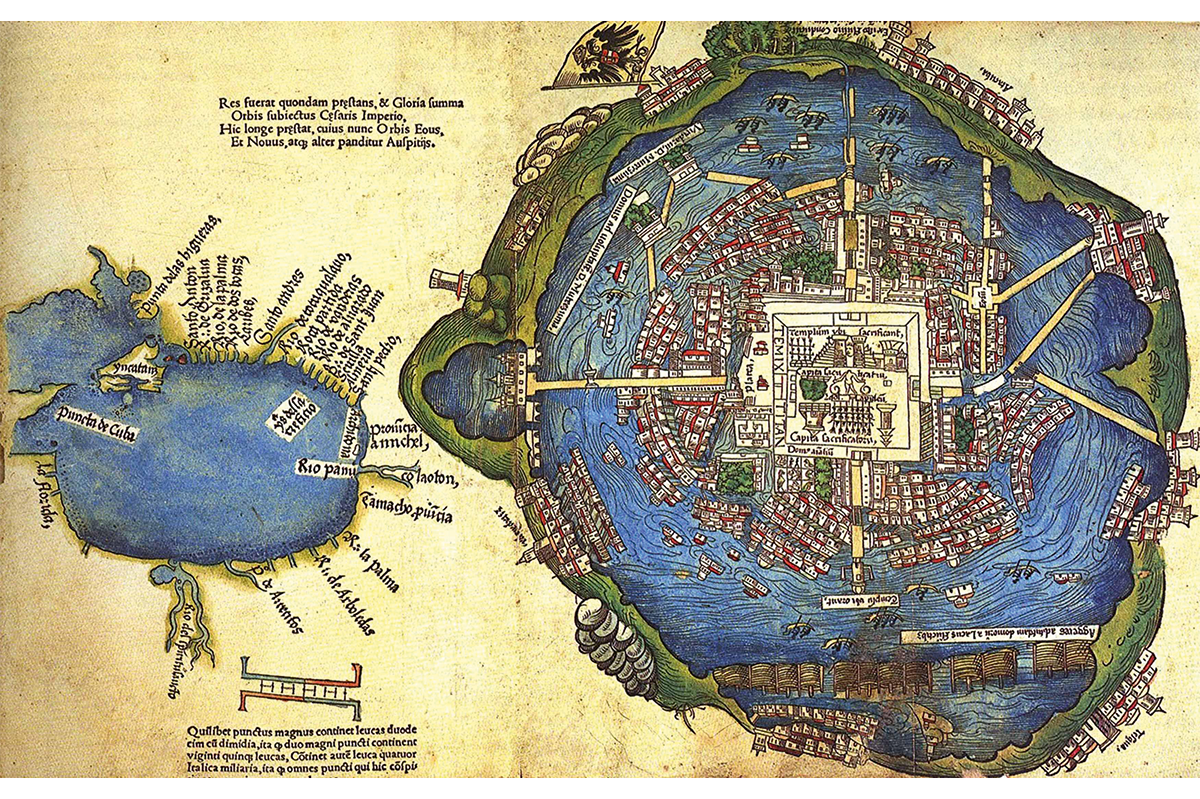

From the end of the eighteenth century until quite recently, the British and American systems were the models to which societies aspiring to democratic government looked. That was especially so in the decades after the defeat of the Axis powers by the Allied democracies in 1945, and again after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 during the imagined End of History.

In the thirty years since then, political naiveté, gross economic mismanagement, historical illiteracy, cultural confusion and demoralization and ideological delusions have brought the Western democracies to near ruin. By the third decade of the twenty-first century, the original salt has lost its savor. It remains to be seen whether democracy in the West can survive its attenuation in the Anglosphere, whence it had its origins eight centuries ago.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s October 2022 World edition.