If ever I pee on the grave of an American it will be that of Robert Moses, the highwayman whose roadbuilding and neighborhood-obliterating projects in New York City and New York State threw half a million people out of their homes, as Robert Caro estimated in his biographical masterpiece The Power Broker. To those who had the temerity to object to their ejection, the monster Moses hissed, “When you operate in an overbuilt metropolis, you have to hack your way with a meat ax. I’m just going to keep right on building. You do the best you can to stop it.”

So it was with teeth gnashing that I drove down Robert Moses Parkway in the city of Niagara Falls, New York, en route to the annual Armenian festival at St. Hagop Armenian Apostolic Church.

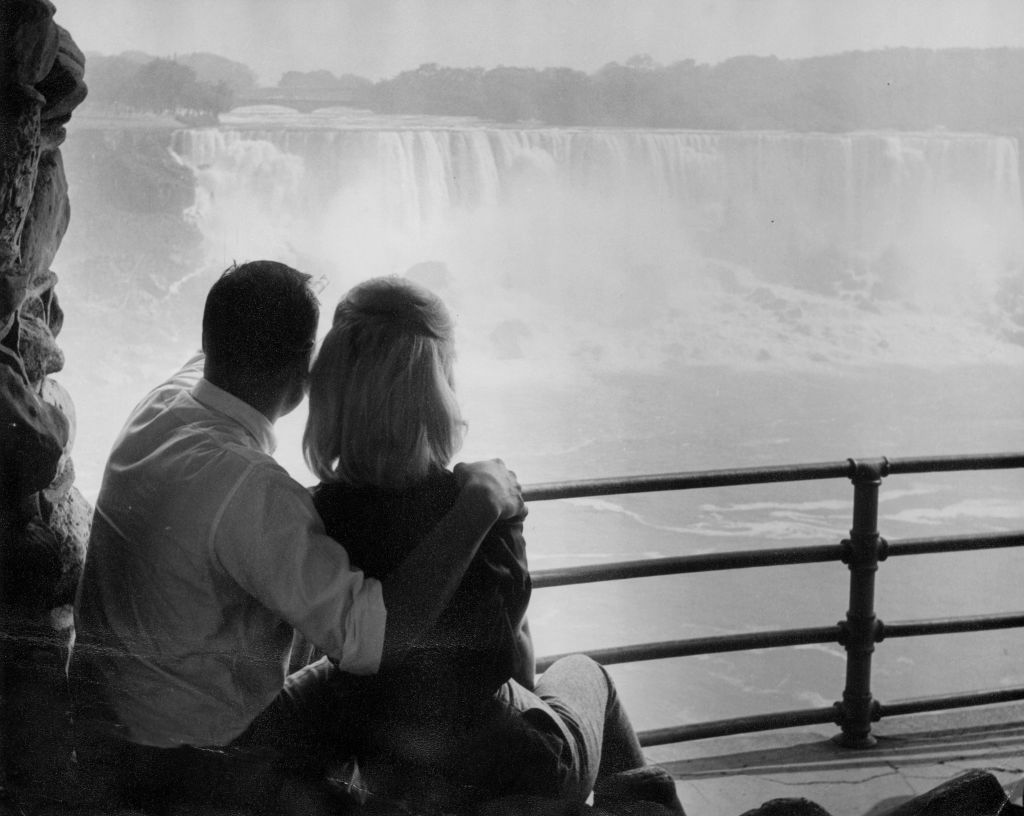

The Niagara Falls themselves — though significantly altered by the hand and blasting tools of man — always inspire awe, contrary to Oscar Wilde’s crack that “every American bride is taken there, and the sight of the stupendous waterfall must certainly be one of the earliest, if not the keenest, disappointments in American married life.”

But the city that shares a name with the nearby cataracts remains a source of utter befuddlement. How on earth can one of the world’s great natural tourist attractions be bordered by hazardous waste sites, hideous Brutalist architecture and block after block of squatter-occupied crack houses? What the hell happened?

The short answer is decades of corruption, destructive urban renewal and deference to bullying Magic Bullet proponents like Robert Moses and the disastrous 1960s mayor, an itinerant Boston University School of Theology-trained minister turned industrial public-relations flack with the risible name E. Dent Lackey. Alas, the Magic Bullets of Moses, Lackey & Co. were aimed directly at the city’s head.

I don’t much mind the carnival barker atmosphere conjured by images of the pre-urban renewed Niagara Falls, with its wax museums and forlorn-hope dreamers scrambling for the loose buck. In retrospect, their vulgar schemes and garish designs — deplored by the likes of Frederick Law Olmsted — had a rascally Mark Twainish charm. My scorn is reserved for the politicians and developers, whose greed and power-lust account for most of the villainy that wrecked modern American cities.

By the early 1960s, wrote Edmund Wilson in Apologies to the Iroquois, the city of Niagara Falls, erstwhile “aviary of honeymooners,” had become “almost indistinguishable from Gary, Indiana.” Thank God St. Hagop still stands, an island of Armenian-American faith and culture in a sea of boarded-up houses.

Lucine, my wife, is half-Armenian, rather like Cher (née Sarkisian) and Kim Kardashian, though with a higher IQ and a less pecunious mate. Her Armenian relatives are a delight, not least because they make the best food on the planet.

Lucine’s late father rekindled my affection for William Saroyan and schooled me in the politics of the Caucasus. His ancestors, some murdered and other displaced by the Turkish genocide, settled in Syria. Vasken came to the United States in the 1950s, acculturating himself in the taverns of Milwaukee by watching Green Bay Packers games on TV and listening to the bar-talk. A soccer player, he developed an appreciation for American football but retained an accent that was part Aleppo-bred Armenian, part Cypriot boarding school.

There is a significant cultural difference and tension between the diaspora Armenians of his and Saroyan’s generations and the Soviet Armenians who came to this country after the dissolution of the USSR, but I leave its exploration to those at Ground Zero in Southern California.

The crowd at St. Hagop seemed distinctly old-school Armenian American. I saw only two Kardashian-imitating girls.

Of course, Lucine and I headed straight for the grub.

The printed menu said that dinners were ten tickets each, and bottled waters one ticket per. I asked how much twenty-two tickets cost. “Twenty-two dollars,” the woman said with a “Duh” tone, as if explaining matters to a simpleton who somehow had wandered in.

“Odar,” my wife whispered to me, using the wonderfully piquant Armenian word for outsider.

“Armo,” I replied.

Hey, I’ve been Armenian-adjacent for thirty-five years now, so I’ve earned the right to mutter a slurry demonym now and then.

Outside the social hall, the high-rise Seneca Niagara casino blots the western horizon. I wonder idly where the Niagara Falls Museum, owned by the family of my friend Sandy Abramson, once stood before Robert Moses’s goons razed it.

We drive out of town, passing the Robert Moses Niagara Hydroelectric Power Station. There’s that word again: power. I’m with Henry Adams: “Power is poison.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2022 World edition.