A visit to another state should be prefaced by reading one of its poets, so for a trip to Greenville, South Carolina, I chose Henry Timrod, the poet laureate of the Confederacy, over Hootie and the Blowfish. ‘Cling to the lowly earth, and be content!’ commanded Timrod, a favorite of Bob Dylan’s. The Nobelist borrowed a few words (‘along yon dim Atlantic line’) from Timrod for ‘Cross the Green Mountain’, an eight-minute Stonewall Jackson-flavored masterpiece he wrote for Ron Maxwell’s Civil War film Gods and Generals (2003). Dylan, an equal opportunity sampler, also filched lines for the song from ‘Come up from the fields father’ by that barbaric yawper of the Union, Walt Whitman.

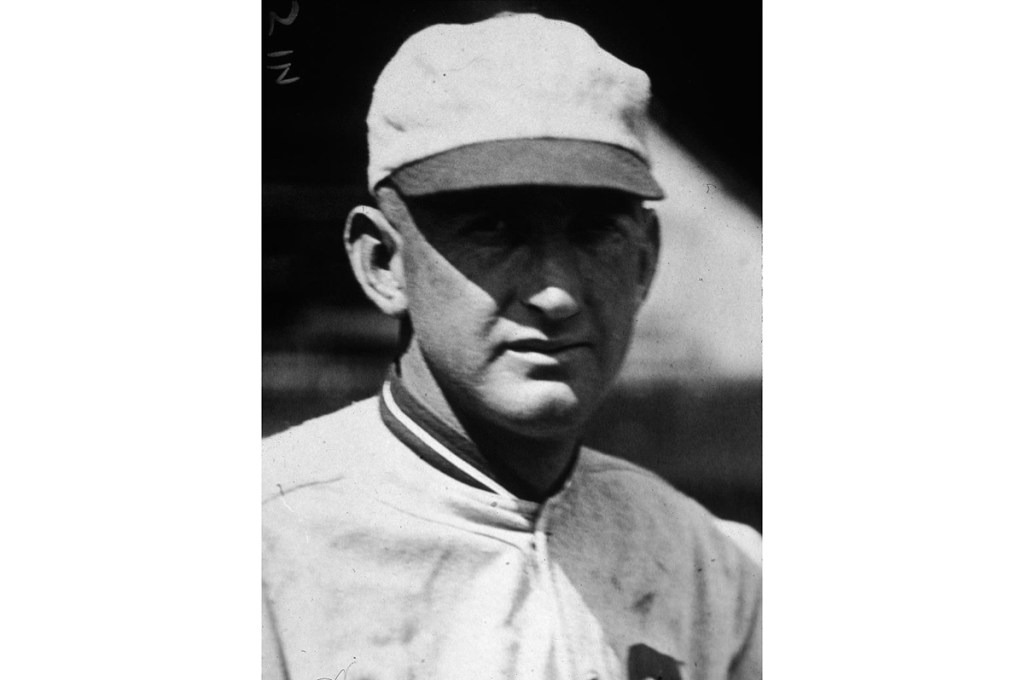

Greenville’s favorite son is the poetically tragic Shoeless Joe Jackson, the illiterate millhand whom Babe Ruth called ‘the greatest hitter I had ever seen’. Shoeless Joe was one of the eight members of the Chicago White Sox who conspired, to various degrees, to throw the 1919 World Series, earning him banishment from Major League Baseball and romanticization in the films Field of Dreams and Eight Men Out.

‘It don’t take school stuff to help a fella play ball,’ observed Joe, though the accounts of Jackson pathetically pretending to read menus and newspapers can soften even the most horsehide-hard heart.

We dropped by Shoeless Joe’s gravesite to pay our respects, removing our footwear for a photo, as surely hundreds of other discalced pilgrims have done over the years. Joe hit well (.375) during the fixed 1919 Series, but most of his base hits were in games that the White Sox (‘Black Sox’ in sportswriterese) were trying to win or that were already out of reach. He made no errors, his defenders point out, but contemporaneous accounts have him lollygagging or standing out of position in the outfield — mistakes more subtle than outright errors but just as costly. I love Shoeless Joe as much as the next sap but he did help the Black Sox tank. The authorities never forgave him for it, but as we live in an unforgiving age (in which both ruth and Ruth have left the building) he is all the more sympathetic. What, you’ve never made a mistake?

Greenville was the cradle of a later famous Jackson, the stylishly shod Reverend Jesse. Heck, I voted for Jesse Jackson twice, in the Democratic presidential primaries of 1984 and 1988, because for all his flaws he genuinely tried to build a biracial alliance of working-class, lower-middle-class and rural people against the ruling class and its flunkies. Jackson failed, of course: the rulers have outwitted us time and again, and so the gross maldistribution of wealth and power in the USA remains unchallenged while We the People argue about which bathroom the quondam Bruce Jenner should use.

Strolling down Greenville’s bustling Main Street, we passed the Poinsett, the hotel in which a young Jesse Jackson worked as a waiter. Jesse once claimed to have spit in the soup of rude white customers. He later recanted, but as his high-school football coach Joe Mathis said, with respect to truth Jackson ‘gives himself a little latitude’. There is ‘always a little space there between what happened and how he’ll tell it’.

A statue of Joel Poinsett graces the sidewalk just beyond the spittle-flecked, soup-serving hotel that bears his last name. Poinsett, a South Carolina politician and naturalist, served as US minister to Mexico in the 1820s. During this diplomatic assignment he plucked red Christmas flowers and sent them to botanists for examination. As reward for his labors the word poinsettia entered the dictionary. Thankfully, the bronze Poinsett seems to have been spared in last summer’s hissy fits. But wasn’t the naming of the poinsettia a clear case of appellative cultural appropriation? Oops — forget I said that.

Greenville is also home to Bob Jones University, a fundamentalist Christian school that formerly dubbed itself ‘The World’s Most Unusual University’. It was once controversial for its ban on interracial dating but that injunction has been junked, belatedly. I was hoping to return home with a suitcase full of t-shirts reading ‘BJU’, thinking I could resell these to ‘awesome!’-saying, PBR-drinking bros, but alas, the realization that the university is unfortunately initialed must have occurred to someone else at some point, so I left empty-handed. The multiracial folks we met at BJU were friendly and helpful.

From H.L. Mencken on, Northern writers have twitted institutions like Bob Jones, but I’ll second John Shelton Reed, the greatest sociologist of the South: ‘I don’t think they have the answer. But they’re not the problem.’ With respect to pleasant Greenville, I defer to Henry Timrod, the shy, short, stuttering South Carolinian from whom Mr Dylan cribbed ‘There is no unimpressive spot on earth,/ The beauty of the stars is over all.’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2021 World edition.