Potato, how do I love thee? Let me count the ways. There are great buttery mountains of mashed Yukon Golds, and then there are oven-roasted wedges with lime, dill and black pepper, or again baked russets with their innards extracted and mashed with sour cream and chives, stuffed back into their jackets, topped with a little grated Parmesan and then toasted under the broiler until golden. Then there are potatoes peeled, chopped in half, bathed in olive oil, salt and lemon, and baked with a little garlic. Fried potatoes are rather nice too. Baby potatoes seared in butter in the Instant Pot are tasty — and can anyone really take exception to a potato roasted in duck fat?

Oh dear. That sounds positively gluttonous. I mean in moderation, of course. One dish at a time, spread out over several weeks. But really, is there any comfort food to beat the potato? It pairs well with cheese, with wine, or with cheese and wine in the case of the heavenly raw-milk cheese Mont d’Or, which I believe is illegal in several countries.

Let me tell you about the Mont d’Or I had the great good fortune to enjoy in Burgundy, not far from the Jura mountains. French Mont d’Or is made from the unpasteurized milk of cows that graze exclusively upon alpine meadows in the Jura.It comes in a lovely wooden box. You remove the top of the box and slice the rind off the top of the cheese, trying not to waste any of the runny deliciousness within. You pour in a few glugs of white wine, preferably one made from grapes harvested on the lower slopes of the Jura mountains. Then it goes into the oven for a while, where the wine and the cheese meld into an unspeakably delightful compound. My wonderful hosts had a sack of Burgundian-grown potatoes from a local farm, which we peeled and boiled up. When all was ready we sat around the table, ladling winy Mont d’Or over our potatoes, talking about the higher things in life and sipping on the rest of the bottle of Jura white. Inoubliable, as the French say.

The star of the show was of course the Mont d’Or, but let’s not forget the prize for best supporting actor, which belonged fairly and squarely to the Burgundian potato. That’s the thing about the potato: it’s not flashy, but for solid, reliable honest-to-goodness worth it can’t be beaten.

Potato historians claim that once European farmers reluctantly accepted the tuber, Europe entered into a new era of plenty, where potatoes formed an easy crop and served as inexpensive food for the poor. There was much kicking at the goad, however, before the potato caught on. The Irish were among the first to get on board the potato train. The vegetable did quite well in Irish soils and was apparently universally enjoyed. Or so they say — it’s always possible that the English wrote the history books and not all Irish loved their praties as much as was reported. However, the potato certainly kept them fed. When potato blight appeared and destroyed the harvest, there was starvation and malnourishment on an absolutely massive scale. A million people died and another two million emigrated. Quite the historical impact, for a mere vegetable.

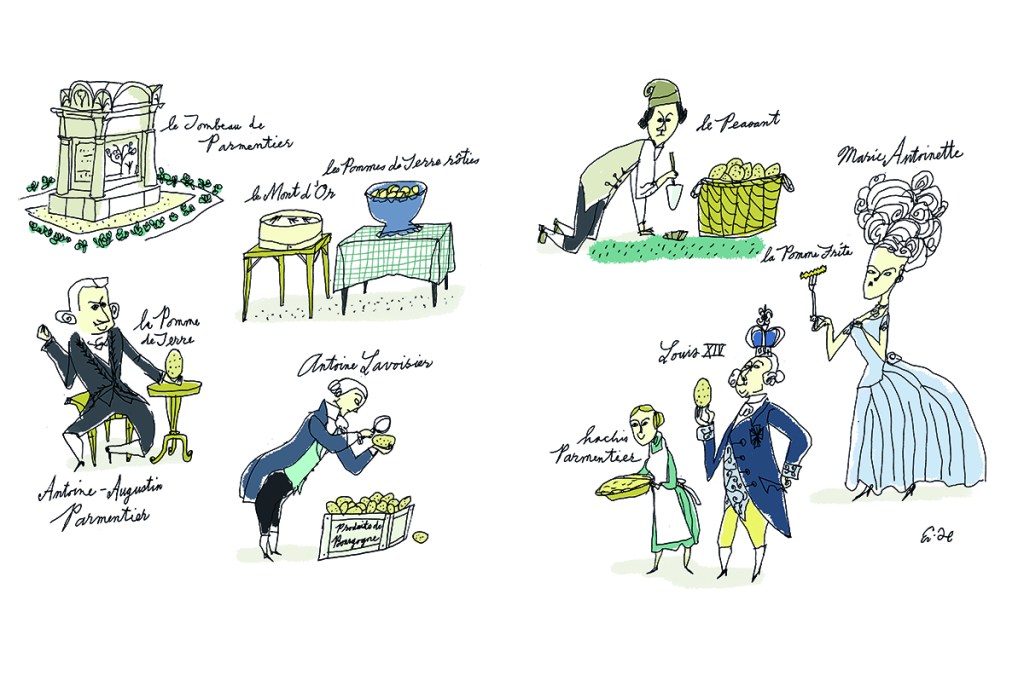

The English were rather snobby about adopting the spud. In the mid-eighteenth century, one political slogan went “No Popery, No Potatoes!” as bigoted farmers associated the potato crop with the Catholic Irish. They came round eventually, but it was a struggle. In France Catholicism was reasonably popular; not so the potato, which the Gallic palate despised and the Gallic pitchfork knew only as animal feed. Through the efforts of one man, pharmacist Antoine-Augustin Parmentier, all this would change.

During the Seven Years’ War, Parmentier served in the army, was taken prisoner and found himself in a Prussian jail, where he was served a steady diet of potatoes. He became interested in their nutritional value, and on his return to France began a campaign to encourage the adoption of the potato by French farmers. Although they already grew it for feed, it was only very rarely consumed by humans, and the health authorities had condemned potatoes as toxic. Parmentier began by writing a series of scientific papers on their nutritional excellence, convincing the Paris Faculty of Medicine to declare the potato edible in 1772.

But changing the culture, as conservatives know all too well, is no easy task. Parmentier was a resourceful character, however, and launched what we would now call a PR campaign to break down popular resistance. He went to the king for help. Louis XVI was quick to grasp the potato’s potential as an alternate food source in case of a bad wheat harvest. He encouraged Parmentier’s efforts and reportedly set a fashion of wearing a purple potato flower in his buttonhole. Marie-Antoinette seconded the king’s efforts by wearing potato flowers in her hair, and the court ladies followed suit.

The king gave Parmentier permission to grow potatoes on an impoverished piece of land that no one thought would produce much of a crop. But the potatoes did well, demonstrating their adaptability to poor soil. As the land belonged to the military, the army maintained a presence, leading people to believe they were guarding a secret crop intended for the wealthy. Thieves came at night-time and stole potatoes away to experiment with, enhancing the potato’s reputation. In 1795, the wheat crop did poorly and Parmentier’s genius was recognized when famine in the north of France was held at bay thanks to the potato.

Parmentier devised potato recipes, including one for bread that he hoped could be used in case of wheat shortages. He organized banquets and invited celebrities such as Benjamin Franklin and the chemist Antoine Lavoisier to tasting events where different potato dishes were served. His name has been deservedly immortalized in a number of recipes, including hachis Parmentier, the French (and in my view superior) version of shepherd’s pie.

Buried in Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, Parmentier lies in state under a monument surrounded by — you guessed it — a potato patch. His memory remains green; every now and then a grateful member of the public comes by to add a potato to the collection on the tomb, marked in Sharpie: “Merci pour les frites.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2022 World edition.