It is increasingly clear that the 1619 Project, foisted on the American public in August by the New York Times, was ill advised. Fatuous, tendentious and tedious, 1619 is more advocacy than history, and is intended mainly to stoke the woke and to keep race on the front burner in the upcoming 2020 elections.

No close observer of the Times over the past few years would have expected otherwise, for in its domestic coverage it reads at times more like a Midtown edition of the Amsterdam News than a national newspaper of record. While still indispensable in some ways, its editorial slant and, indeed, news coverage have become unmoored. Three years of Donald Trump (and the prospect of four more) will do that to some liberals — and liberal organs, too, as a look at the 1619 Project will attest.

The value of the Project’s interpretation of American history, with apologies to Churchill, is this: never has so little been owed by so many to so few.

Major scholars have already weighed in on the egregious problems in various parts of the Project, including luminaries such as Gordon Wood and Sean Wilentz on the Revolutionary era and James McPherson on the antebellum era and the coming of the Civil War. So here I will focus my attention on the early period of American history, including the year 1619. What we find is an overriding interpretative architecture characterized by mischaracterizations, elisions and distortions, a ‘presentist’ ransacking of the past, manufacturing a fake history for use today.

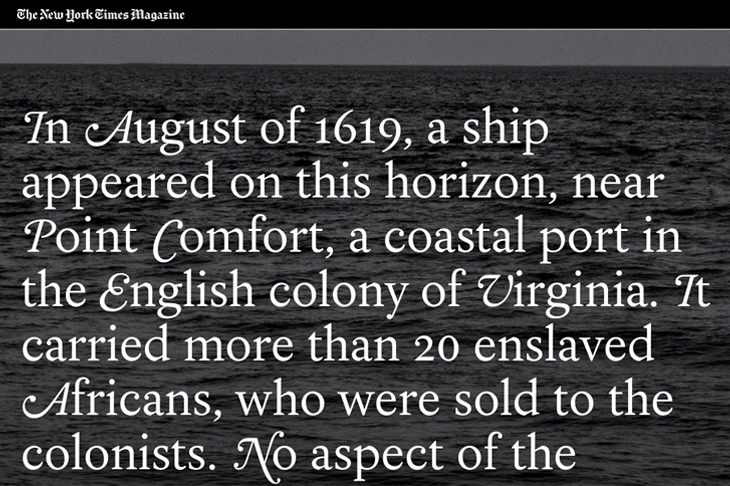

The 1619 Project argues assiduously for the precocious importance of slavery and race in British North America, particularly because of the chance arrival in Virginia in 1619 of ‘some 20. and odd Negroes’, who were sold either as indentured servants or slaves. By this, the organizers and editors of the 1619 Project signal their desire to flatten American history through interpretive bludgeoning. Simply put, the year 1619 is of little historical importance to Africans, African Americans, White Americans or really to anyone not currently working at 620 Eighth Avenue in New York City.

As numerous historians of British and Spanish America have long pointed out, Africans, including enslaved Africans, were present in North America well before 1619, and some for almost a century. Indeed, if the 1619 editorial crew hadn’t been so avid to link its project with 2019 — and, more to the point, November 2020 — it could have waited until 2026 and marked (at least) the 500th year since the first traces of African slaves in North America. That would have meant nodding in the direction of the short-lived Spanish settlement of San Miguel de Gualdape, founded by Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón at some still debated site along the southeast coast of present-day South Carolina or Georgia, its demise due in part to a slave revolt.

Scholars such as Michael Guasco, writing in 2017 in Black Perspectives, have already called attention to the ‘overstated significance of 1619’. Several generations of careful scholarly work on the origins of racial slavery in Virginia —by historians both black and white — have demonstrated that the process by which the status of Africans became differentiated and then fixed juridically was slow and incremental, involving much ambiguity, with both forward and backward steps. It wasn’t until the second half of the 17th century that the process began to be codified. Only in the last quarter of the 17th century did African and African American slavery begin to achieve any substantive importance in British North America.

Indeed, if one is interested in slavery in North America in 1619 and the first half of the 17th century, one would think first of Native Americans and the Spanish, not Africans and the English. Native Americans were mainly enslaved in indigenous communities or in silver-mining areas under control of the Spanish in the southwest. There were also Native American slaves — and African and African American slaves too — in Spanish Florida, as well as relatively small numbers of enslaved Native Americans in French Canada and in the seaboard colonies organized under the English. Figures are hard to come by but Andrés Reséndez, in his award-winning book The Other Slavery (2016), offers a rough estimate of somewhere between 10,000 and 45,000 Native American slaves in North America (north of Mexico) during that period. Others would put the figure even higher. African and African American slaves in British North America? Only small numbers.

With this in mind, it seems fair to suggest that if one were searching for truly important historical developments around the time of the arrival at Point Comfort, Virginia of the English privateer White Lion with its cargo of Africans, the smart money would be on 1618. That was the year of the onset of the Thirty Years’ War, which was to lead to millions of deaths and was to fundamentally reshape Western geopolitics and religious history. The even smarter money might be even on 1620, the year of publication of Francis Bacon’s Novum Organum, wherein Bacon systematized and synthesized natural philosophy to promote inductive reasoning, one of the pillars of the scientific method, which in time was to transform human history far more than anything that happened in Virginia in 1619.

The great French historian Marc Bloch wrote many years ago in The Historian’s Craft about the ‘idol of origins’. When people make the common error of fixating on beginnings, they run the risk of ‘confusing ancestry with explanation’. The principals in the New York Times’s project seem to be doing just that in their effort to establish an unrelenting and remorseless 400-year genealogy of unmitigated white-on-black racism in the United States, beginning with the landing of ‘some 20. and odd Negroes’ at Point Comfort in 1619.

Slavery was, and indeed still is, an enormity. Figures compiled by a variety of organizations, ranging from the Free the Slaves advocacy group to the International Labour Organization (ILO), suggest that there are roughly three times as many slaves in the world today than were trafficked during the entire history of the Atlantic slave trade. To be sure, the figure for today derives in technical terms from a ‘stock’ concept (a measurement made at a given point in time, which can be the result of accumulated flows), whereas the figure for the Atlantic slave trade derives from a ‘flow’ concept (a measurement made over a given period of time). But the difference between the two is nonetheless worth noting.

To invoke ‘modern’ slavery is not to downplay the historical horrors of the Atlantic slave trade, only to call attention to the continuing horror of slavery amongst vulnerable groups and individuals, and to guard against what the great Marxist historian E.P. Thompson referred to as ‘the enormous condescension of posterity’ toward actors and actions in the past.

The New York Times is peddling a linear narrative of national shame, its principal theme invariant racial oppression, or, to be more specific, the incessant depredations by villainous — or at best acquiescent — whites against friendless blacks. And this throbbing narrative allegedly began in 1619. But history, pace Nikole Hannah-Jones, doesn’t often work that way. Linearity works for certain problems — Ohm’s law in electricity and electromagnetics, for example — but not for others. Linearity certainly does not work for history, which is complex and polychromatic, circuitous and irregular. History, alas, is rather more tragedy than melodrama, and is not color-coded.

An example: in 1981, Yale University Press published a book by Ray Huang, a distinguished historian of China, entitled 1587: A Year of No Significance. The title derived from the fact that in Huang’s view nothing very important happened in that year late in the Ming Dynasty. To be sure, the author was being playful, even a bit arch with this title: one can, if so inclined, find in the incidents detailed in the book intimations of what Jonathan Spence referred to in a review as ‘future drama’, if not ‘impending catastrophe’ relating to the Ming dynasty’s collapse a little over a half century later. But no one thought so at the time. And no one in 1619 thought as the New York Times does in 2019, or would have us think in 2020.