On January 8, 2015, the day after eight Charlie Hebdo satirists and four others were murdered, a posthumous cartoon by one of the victims appeared in France’s answer to Private Eye. It showed two decrepit-looking authors side by side at a book signing, with the caption “71 percent of the French are pessimistic.” One was Michel Houellebecq, hawking his novel Soumission, which imagined a France that out of sheer malaise elects an Islamist president; the other was the then-journalist Éric Zemmour, with his own Le Suicide Français.

As an encapsulation of the mood of France, it was hard to beat. Soumission went on to sell 800,000 copies; Le Suicide Français, in which Zemmour ranted against the decline and fall of French civilization, sold 500,000. Both Houellebecq and Zemmour have been threatened with the fate of the Charlie journalists. Both now live under police protection.

Last Friday, on the seventh anniversary of the murders — and as two polls suggested Éric Zemmour could get to the second round against Emmanuel Macron in the presidential election next April — Houellebecq’s eighth novel, Anéantir (annihilation), came out with the kind of reception France does best.

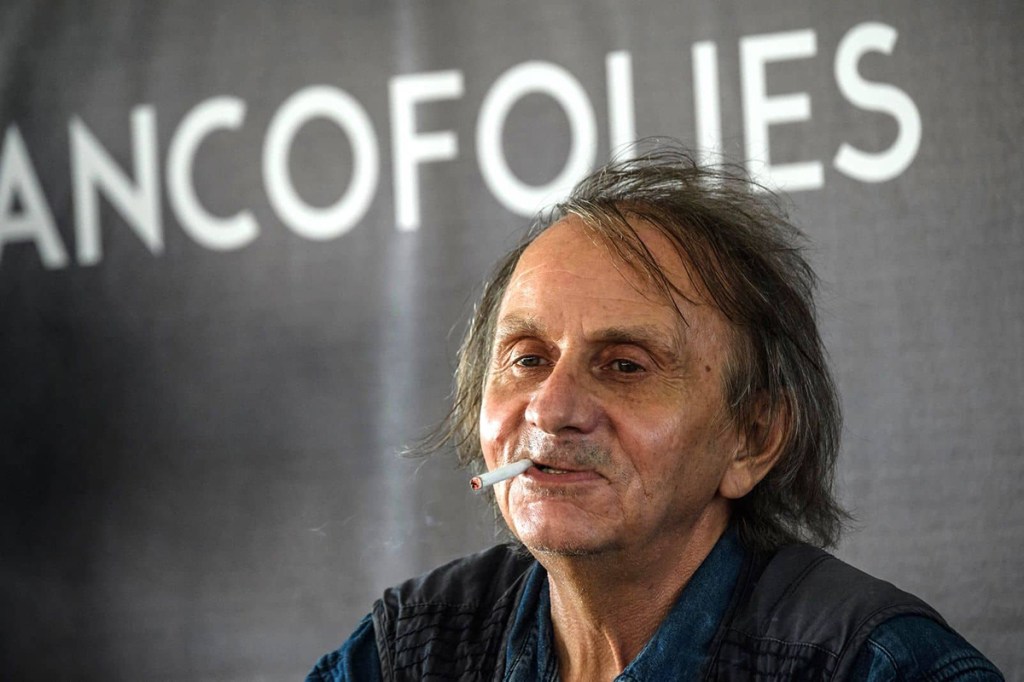

The French papers have been filled with pieces on “le phénomène Houellebecq.” The 65-year-old was roundly abused by a panel of critics on France Culture, the state broadcaster’s highbrow radio. “Flat style… badly-constructed… leading nowhere… the author’s obsession with constructing his own literary myth… the sheer boredom emanating from these 736 pages… perverse trivialization of a far-rightist outlook,” on and on, the perfect seasoning of barely-repressed envious rage. It was a true succès de scandale, as described in Balzac’s Les Illusions Perdues, his 1837 description of Parisian literary and journalistic circles.

As it happens, Balzac is Houellebecq’s hero. Anéantir not only demonstrates comparable ambition to Balzac; it is also proof of Houellebecq’s tireless work. In his various books he has accumulated notes on: the stages of terminal tongue cancer; the precise topography of the Ministry of Finance; the exact operation of a guillotine (with schematics); the names, composition and texture of processed sandwiches on sale in Parisian train stations; the vernacular of Paris’s best political spin doctor; the triage of dying residents in provincial care homes, and more. When, some time around the 2100s Anéantir is re-published by Penguin Classics, the notes section will take up half the space of the novel proper. The translator will battle to properly convey the Tom Wolfe-like bleak hopelessness encompassed in “un sandwich Daunat maxi-moelleux au blanc de poulet-emmental dans son emballage et une Tourtel.”

Like Balzac, many of Houellebecq’s characters are drawn from real life. The book is set in the year 2026. The sitting president is transparently Emmanuel Macron, who’s been re-elected in 2022. Term limits mean he can’t run again: his cunning plan is to push a popular television talk show host to win in 2027, coached by, among others, the minister of finance, thereby keeping the seat warm for a return of “Macron” himself at the 2032 election — a kind of Putin-Medvedev switcheroo. The president remains in the background while the minister, Bruno Juge, is transparently modeled on the actual finance minister, Bruno Le Maire. He is a man who, like his character, has been known to nourish presidential dreams himself, and is a friend of Houellebecq’s.

The unconfined joy of Bruno Le Maire in finding himself portrayed in a Houellebecq novel has become one of the most enjoyable spectacles in Paris. No rank in the Légion d’Honneur remotely compares with this kind of literary immortality. Le Maire met Houellebecq some fifteen years ago, when helping him get his dog through customs. Never mind that in the novel “Bruno Juge dumps his wife of twenty-five years, or that a terrorist viral video shows, realistically, his decapitation,” writes Le Monde’s Ariane Chemin, one of the paper’s star correspondents, who notes the exact similarities of the minister’s office in the book and the room where Le Maire received her for a recent interview.

The actual hero of the novel is Paul, the minister’s chief advisor, one of those technocratic French civil servants not unlike those who gave Britain such grief over Brexit. Inexorably, intercut with asides and sharp scenes of Parisian life, the story progresses to the personal: Paul’s dying father, his own reckoning with illness, the support of the wife he long neglected, each obsessed with their own parallel careers. It’s typically Houellebecquien to say that a book that ends in devastation and death is “my most hopeful yet,” but it is no lie.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.