As a fan of early jazz, I’ve read a great deal about Kansas City as it was in the 1930s. A most attractive place it seems in retrospect, of 24-hour drinking and gambling, to the accompaniment of wonderful music provided by young, prodigiously talented and mostly black instrumentalists and singers; a wide-open city ruled over by a corrupt mayor, Boss Pendergast, whose main duty seems to have been to keep the good times rolling. It is at this time and in this place that the novel Mrs Bridge (1959) by Evan S. Connell is set, but Mrs Bridge’s life elapses without a mention of any of these goings-on.

For Mrs Bridge lives in a wealthy suburb of Kansas City, inhabited by respectable and well-off families, most of whom vote Republican in a United States recently carried in a landslide victory by Roosevelt and the Democrats. The Depression hardly affects the Bridges or their neighbors. Their only contact with black people is to employ them as servants, and those servants go home at night to parts of the city the Bridges would not dream of visiting. The genius of Connell is to show that this is how most people live: first in their own minds, then in their families, then in their limited social circles; most historical novels fail to realize that most people simply do not notice whatever great moments of history are being enacted around them unless they actually impinge upon their lives.

The odd thing is that Evan S. Connell, on the face of it, looks the sort more likely to have written a great novel about all that exciting stuff happening on the other side of Kansas City. He was born in the city in 1924, the son of a doctor he described as a ‘rather severe man’. Connell dropped out of medical school in 1943 and joined the Navy, training as a pilot. After the war he traveled and wrote and worked at any odd job he could find. Every book he produced is well worth reading: the poetry, the essays, biographies and short stories. For most of his long life (he died at the age of 88) his talents went largely unrecognized.

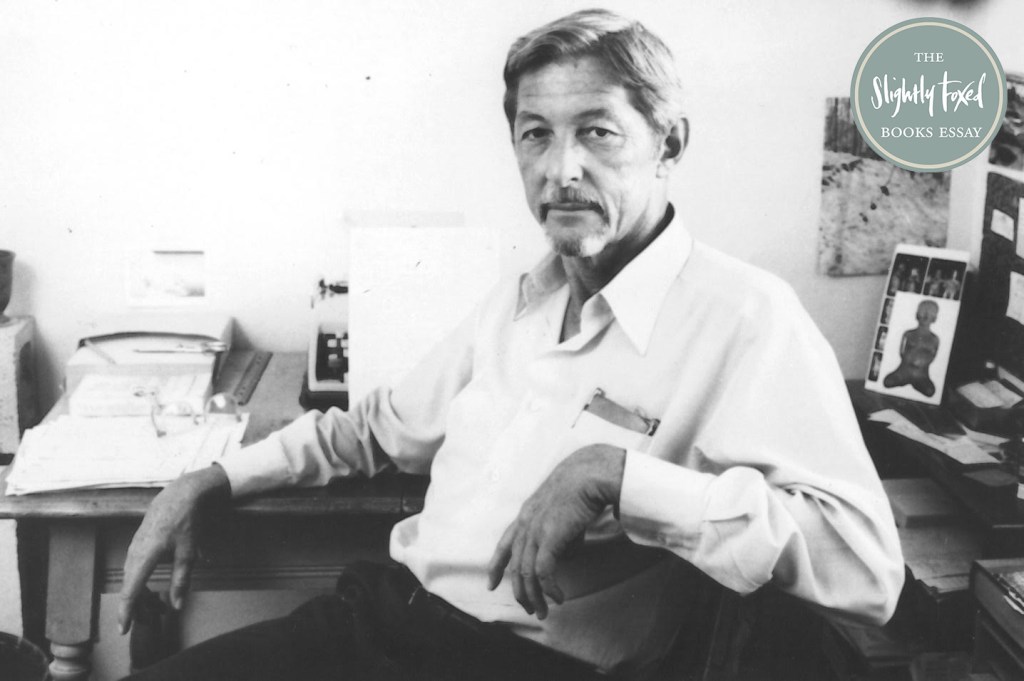

The problem was he was that nightmare of publishers, a writer whose every book is different. Indeed, his life seems to have been lived almost deliberately in a contrary way to expectations. He was handsome – photographs show a lean, tall man with a fine hawk-like head, as if Gary Cooper were miscast as Ernest Hemingway. Unlike most of his contemporaries among American writers he was not a boozer or an academic. He never married but remained all his life, in a curious phrase from one of his obituaries, ‘potently attractive to women’. He lived alone. Taciturn, he became so silent in old age that he was taken for a mute.

Mrs Bridge is the finest of his novels. It adopts a highly original way of telling its story, broken down into 117 vignettes, some barely a page long, such as Mrs Bridge’s comic difficulties in parking her car. Another, several pages longer, gives us a description of a dinner at the country club, where her admirably imperturbable husband insists on finishing his steak while rain and wind whip at the windows and all the other diners have fled to the cellar to escape a rapidly approaching tornado.

The very first sentence of the novel sums up Mrs Bridge: ‘Her first name was India – she was never able to get used to it.’ Her whole childhood is passed over in a few sentences – and there is not a sentence in the whole book which is not of importance – and she marries at the foot of page one. The history of her emotional life in marriage is brief and both chilling and compassionate:

‘For a while after her marriage she was in such demand that it was not unpleasant when he fell asleep. Presently, however, he began sleeping all night, and it was then she awoke more frequently, and looked into the darkness, wondering about the nature of men, doubtful of the future, until at last there came a night when she shook her husband awake and spoke of her own desire. Affably he placed one of his long white arms around her waist; she turned to him then, contentedly, expectant and secure. However nothing else occurred, and in a few minutes he had gone back to sleep.’

Despite this cooling off, three children are born to them, Ruth, Carolyn and Douglas, within two or three years of each other. Their parents ‘let it go at that; there would have been no sense in continuing what would soon have become amusing to other people’.

With her husband working hard every day and sometimes into the evenings, most of the children’s upbringing falls on her. She values above all what she hopes will be ‘their nice manners, their pleasant dispositions, and their cleanliness, for these were qualities she valued above all others’. Unfortunately, ‘what she stressed was not at all what they remembered as they grew older’.

What is truly compelling about Mrs Bridge is her very ordinariness, notwithstanding all her petty snobbery, conformism and timidity. The list is easy to make and appears to be a fairly damning indictment, but Connell is not writing a satirical portrait. His intention is to show us the utter uniqueness of this one human life, the irreplaceability of body and soul that is India Bridge. Connell portrays her so tenderly that we come to sympathize with her and, more, to care for her.

She is frequently puzzled and worried by her children. Ruth grows into a beautiful and wayward young woman. Carolyn is more straightforward, but also interested in boys – Mrs Bridge accidentally eavesdrops on a boyfriend impatiently asking the teenage Carolyn if she is going to remain a virgin forever. When Ruth quits high school at 18 she moves to New York. Of all the family, it is only Douglas who lives in a state of uncomplicated freedom. At the age of 12, he alarms his mother by beginning to build a tower from trash he has collected. The tower grows taller and taller and begins to be noticed by the neighbors. The reaction of her neighbors is what truly alarms Mrs Bridge and she calls the fire brigade. The tower has been cemented together so solidly by the boy that it takes the men four hours to dismantle it, while Douglas watches them ‘in grieved silence’.

There is also perfectly observed comedy and absurdity in the book. The Van Metres, Wilhelm and Susan, are older than the Bridges and the sort of friends acquired almost by accident: ‘Mrs Bridge could not quite recall how she and her husband became acquainted with the Van Metres, or how they got into the habit of exchanging dinners once in a while.’ Wilhelm entertains his friends at the country club; but now the dining-room is almost always empty and the place has fallen out of fashion.

Wilhelm is consummately boring, given to utterances such as ‘I am commencing to wonder if we have a waiter this evening.’ Conversation is desultory and tedious; Mrs Bridge politely agrees with everything that’s said, but at one point in the evening even she wonders if she is about to lose control of herself.

Time passes. She takes up Spanish and then a painting course but abandons both. Harriet, her cook and cleaner, does all the housework and Mrs Bridge tries to fill the emptiness of too much leisure.

Mrs Bridge’s deepest and most tragic desire, we feel, is that every- thing should remain the same, forever poised at its happiest. What disturbs her is the progress of time, which makes her beloved and innocent children into awkward adolescents, then into grown-up individuals whose worlds – Ruth’s sexually promiscuous life in New York, Carolyn’s marriage to a dull but violent husband, the sturdy, self-sufficient young man in Army uniform that Douglas has become by the end of the book when America is at war – are incomprehensible to her.

Connell wrote a second novel, called Mr Bridge (1969), also a closely detailed portrait. It is terrifying how little the two portraits have in common – they might be describing two entirely different worlds. Paul Newman and his wife Joanne Woodward made a film, Mr and Mrs Bridge (1990), that was a conflation of the two. A good, sensitive film that somehow missed the point of the essential loneliness of these two life partners.

Mrs Bridge remains the one to read: a book that begins in carefully observed and often very funny social comedy and darkens into a woman’s meditations, only half comprehended, on the triumphs and failures of her life. It is a masterpiece of empathy with its subject. As Dorothy Parker said, ‘How it is done I only wish I knew.’

William Palmer’s latest novel isThe Devil Is White (Cape). This essay was originally published in Slightly Foxed: The Real Reader’s Quarterly. Slightly Foxed introduces readers all over the world to good books from the past and present.