You might not have heard about sensitivity readers, but in America they are already an essential part of fiction.

Sensitivity readers are freelance copy editors who publishers pay to cancel-proof their new books. They read books that feature identities or experiences that are outside of the lived experience of the author. They then critique the writing through the prism of what they claim to be their own authoritative life experience to guide the author toward more authentic representation. For example, the white author Jodi Picoult used a sensitivity reader for her novel about a black nurse who cares for the children of white supremacists.

For critics, these individuals are the latest stage of the culture wars: woke-ifying new books before readers even have the chance to read them. For publishers they offer a seductively cheap way of reducing the risk of a book or its author being cancelled and the ensuing reputational and profit damage to the firm.

To become a sensitivity reader you have to advertise your suffering — create and market a résumé of otherness, of emotional pain, trauma, credentializing your oppression to enter a victim-for-hire system. Salt and Sage, for example, is a market leader in this industry. It offers dozens of sensitivity and expert readers whose online profiles enable the public to browse consultants with a panoply of experiences. They range from the ethnic and cultural (Afro-Brazilian, Christian, Native American) to the traumatic (emotional/mental abuse by a parent, rape survivor, institutionalization in mental hospital) to the interest-based (cheese-making, equestrianism, tabletop gaming, K-pop).

When read as a list, the incongruity of each reader’s profile can be darkly comic. One person’s list includes ‘LGBTQ…abusive relationships…schizophrenia, Pilates…law school…vegan lifestyle…use of an EpiPen’. Almost all of the readers seem to use their full names, unfazed by making public their most intimate and traumatic experiences.

The more common the experience the reader caters to, the more difficult I imagine it is to speak for everyone. My friend Ray, who is nonbinary and mixed race, is a freelance reader for Salt and Sage. They say much of their reading involves checking for simple, widely applicable errors. ‘It’s…about what wouldn’t make sense, like, someone with my hair wouldn’t go swimming right after doing their hair,’ they say.

When their criticism does tend toward revision, Ray says it is usually for glaringly obvious racist stereotypes, especially in books for children. Some of their clients are self-published authors of books for children, who are paying out-of-pocket for a sensitivity reading. For these clients, much of their work involves catching negative imagery that an author may not see themselves. One client of Ray’s wrote a young adult novel that featured a black character who transmogrified into an ape, which Ray suggested they change because of the obvious racist history of the comparison.

If editors don’t have the ‘diversity of experience’ that would allow them to authoritatively give their opinions on manuscripts, they can farm out the work to people with these identities, for, in Salt and Sage’s case, 0.009 cents per word — much cheaper than employing someone full-time.

It seems as though the creation of the role of sensitivity reader allows the largely white full-time editorial staff of publishing houses the ability to subcontract the work of ‘being a minority’ to freelancers and young gig-economy workers, keeping the most socially vulnerable in the most vulnerable financial positions.

‘Our company just raised the rates,’ Ray says, ‘which is great because the work is very emotionally exhausting. But I could never make a living on just this.’

Penguin Random House’s ‘author news’ page has a blog post that recommends working with a reader, and outlines the steps to finding a good match, linking to a sensitivity reader database called ‘Writing in the Margins’. Meanwhile, publishing houses are freed from genuinely diversifying their staff without sacrificing their avowed commitment to diversity.

‘I interned at a major publishing house…as an editorial assistant…and I was the darkest person there,’ says Ray, who has one black parent. But where their experience as a person of color was valuable in their job as a sensitivity reader for another firm, pointing out the glaring issue of a total lack of in-office diversity was not. ‘Things [about race] would come up in the office,’ they say, ‘and if you’re not in a sensitivity reader role…you’re definitely not supposed to bring it up.’

A few weeks ago I was hiding from the rain under a tree on London’s Hampstead Heath, huddled together with a young literary agent I had just met at a party the clouds intended to spoil. We were sipping prosecco from plastic cups and talking about the usual topics available to bookish near-strangers with few mutual friends to gossip about: new fiction, Olivia Laing’s haircut, a mutual distaste for (but invariable inability to stop talking about) Sally Rooney. As the rain began to quicken, we turned to a new subject: authenticity, and writing from lived experience.

The literary agent told me that sensitivity readers have not yet become popular in London, but that the feeling that people should write only what they know is on the rise.

‘An editor,’ he whispered, ‘recently said in complete earnest she thinks it’s offensive for men to write female characters because they don’t have the experience of being female.’

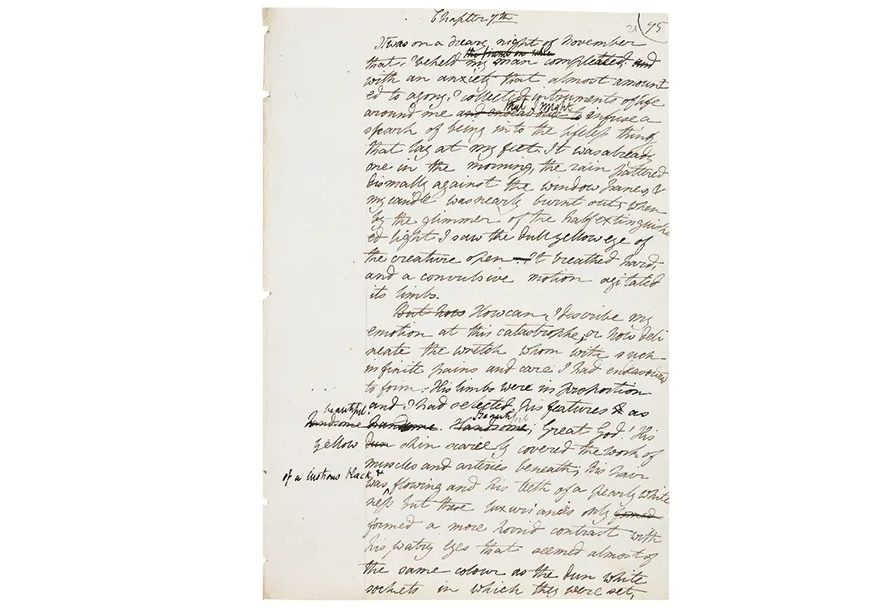

I gasped, not because what the editor had said was shocking, but because it was a perfect crystallization of this obsession with depicting reality and lived experience pushed to its logical conclusion. Are novels meant to be a perfect reflection of reality, or do they communicate to the reader the thoughts and beliefs of the writer or the society he lives in — including the sick, twisted, uncomfortable thoughts?

Beyond the obvious reasons why men should be able to write female characters — that male writers have given us some of our best literary figures, such as Anna Karenina and Emma Bovary — could anyone genuinely believe that women should not appear in novels written by men? Is it not at all interesting as a woman to read what a male author might think about women, or what characteristics he may imbue a female character with, even if the things he has to say about women are perverse and misogynistic? If a woman sensitivity reader gave notes back on female characters in Portnoy’s Complaint, would we still have one of the best depictions of unbridled misogyny ever written, a book beloved by many feminists for its unflinchingly honest portrayal of the thoughts of men?

If the book was read by a female sensitivity reader, how would she be able to take into account the broad and varied life experience of all women? How does the experience of one individual relate to the collective experience of all? I could just imagine a female sensitivity reader marking up the proofs of Anna Karenina and writing: ‘It’s not believable that a woman would jump in front of a train because she thinks her boyfriend cheated on her.’ Would they then have to find a woman who had jumped out in front of a train?

This obsession with reading for verisimilitude in literature may seem hyper-contemporary — as if it were coeval with the current self-reflexive style of autofiction — but it is a practice that dates to the beginning of mass publishing. Only the target for the ‘sensitivity-readers’ has changed.

Publishers have had readers who pre-read the ‘slush pile’ since the advent of publishing, fishing out manuscripts from obscurity and recommending them to the editors. ‘If authors were as prompt to recognize the services of publishers’ readers as they are to criticize them,’ the publisher Stanley Unwin wrote in 1946, ‘the public would learn with surprise how much it owes to a group of conscientious men and women of whose existence it is barely aware.’

In the latter half of the 19th century, Geraldine Jewsbury was a reader and editor for the publishers Bentley and Son, which published Dickens. When Jewsbury decided to accept or reject a manuscript, historian Jeanne Fahnestock writes: ‘Miss Jewsbury often gave her opinion on what subjects could or could not be treated in fiction.’ Jewsbury excised portions of a novel that fictionalized the life of Jesus Christ because ‘she wanted a fictional account to be accurate to the facts as she knew them’. Only with the rise of secularization was the characterization of Christ in fiction seen as acceptable.

Is writing about another group’s identity the same kind of time-designated taboo that the Victorians had regarding writing about Jesus? It has been argued that the concept of personal identity, solidified by John Locke, only took root after people had abandoned their belief in souls. What comes after personal identity? Perhaps the importance we place on lived-experience will one day seem as foreign as the medieval preoccupation with the soul.

Last week while I was researching fairy tales for a story, I read a German folktale collected by the Brothers Grimm called ‘The Jew Among the Thorns’. The story, which has been told in various iterations since the 15th century, is about a man with a magical violin that forces people to dance. He uses it to make a ‘moneylending Jew’ thrash about in the thorn bushes to the delight of a German town. Despite being well acquainted with the history of anti-Semitism, reading the story was upsetting and surprising — this was a folktale in wide enough circulation to be part of the first edition of the Grimms’ Children’s and Household Tales, and told at bedtime.

There is undeniably a great importance in sensitivity-reading stories for children, making sure that the racist narratives and stereotypes adults can recognize won’t be regenerated in the unconscious of future generations. That said, as I sat reading the story, I experienced the way that fiction can more powerfully convey the attitudes of a time than information contained in a history book, and I was glad (in a strange way) to have a record of these disturbing feelings.

As a fiction writer myself, I don’t think that I would hire a sensitivity reader. While researching the topic, my mind wasn’t completely made up until I saw a tweet from a writer and sensitivity reader who said ‘i have over six years and dozens of projects experience as a #sensitivityreader for trans women characters. you don’t need to wait for twitter to call out your book, you can hire me to prevent that from happening’.

That tweet — which feels a bit like a threat — made me understand that I agree, a sensitivity reader could easily protect me from the outrage of the internet, but why should I be so lazy in my exercise of empathy that I allow someone else to have a monopoly on sensitivity? Shouldn’t I need to research my subject? Though I don’t believe you should only write what you know, if you legitimately do not have someone in your personal or professional orbit who can help you to understand if something you’ve written is offensive, and you don’t have the ability to figure it out for yourself through research, reading, or the exercise of compassion, I don’t think that you should be able to hire, for the price of 0.009 cents a word, someone to make your fiction more palatable to the public. If I were to make a bigoted faux-pas, isn’t it better that it remains in my text, outing me as a bigot?

Some sensitivity reading is important, but often it seems less like a check on upsetting and harmful language than a safeguard against white, straight, middle-class authors and publishers needing to change their social circles, ideologies or publishing staff in any way.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.