Peter Bogdanovich’s new documentary about Buster Keaton, The Great Buster, is a match made in movie heaven. I can’t think of two men more devoted to making motion pictures — huge successes in their day — more acquainted with the merciless climate of Hollywood, or more aware that they were as instrumental in their own downfalls as in their glories.

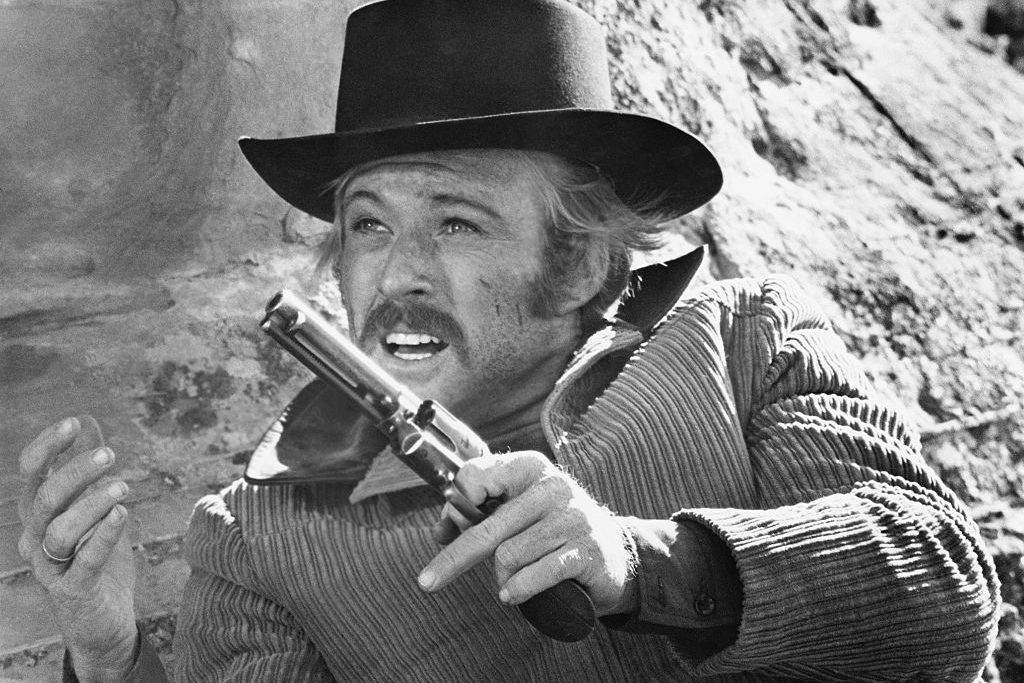

‘Buster said he made the great mistake of his life in 1928,’ says Bogdanovich. ‘He had done these masterpieces in the 1920s — Steamboat Bill Jr, Sherlock Jr, The Navigator, The General — and done them the way he wanted with his own production unit… It couldn’t get any better. But then [he was] told to sign with MGM. And Buster was never the same again. The studio interfered in his pictures. His marriage to Natalie Talmadge collapsed. He drank himself stupid. It happens — he fucked up. I’ve done the same myself. He was a master at silent comedy, using physical space, doing his own stunts, composing comedy as if it was music. But maybe sound would have finished him, too.’

In his documentary, we see an 80-year-old Bogdanovich surveying the images of Buster Keaton from nearly 100 years ago. He watches Keaton in The General trying to guide a locomotive through the mayhem of the Civil War, keeping a straight face in every ordeal. There is an affinity between Keaton’s beautiful but stricken face and Bogdanovich — austere, cool, always with his knotted cravat, but drained of illusion.

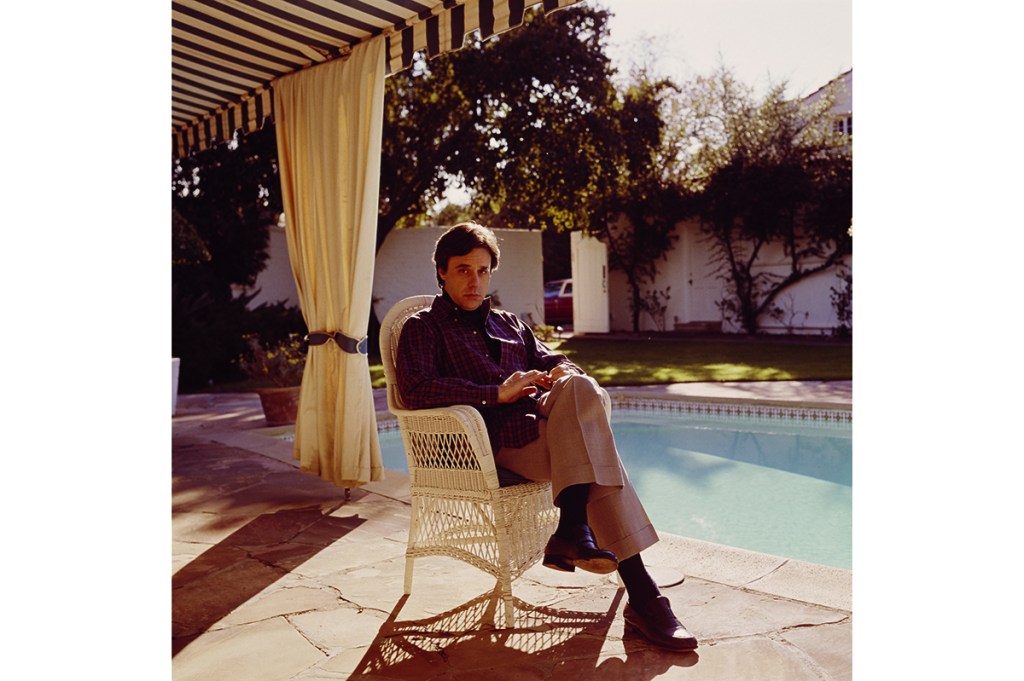

Bogdanovich’s father was a painter who had come from Serbia; his mother was Viennese. The couple arrived in New York three months before Peter was born in July 1939. The kid was brilliant, but a touch arrogant, and he wanted to be an actor. He admits that longing never went away, so he has acted out his life.

‘I started seeing pictures — several hundred a year — and I always preferred old movies.’ He curated programs on Howard Hawks, John Ford and Orson Welles in New York. And he married Polly Platt, a costume designer in theater who went on to work on his early films. ‘What did Polly mean to my career?’ he muses. ‘That’s a good question. We were in love. We became parents [two daughters], and we went to Los Angeles together, full of dreams.’

That’s how they got to make their first film Targets (1968) for producer Roger Corman. It was conjured out of thin air. Corman was owed a few days’ work by Boris Karloff. There was spare footage from a Karloff picture. Throw in $100,000 — could they make a movie out of that? Targets was a mix of inspiration and desperation, based on a 1966 shooting rampage.

‘One thing led to another. Targets got noticed, and we were into our dream.’ That turned out to be three great hits in a row: The Last Picture Show (1971), What’s Up, Doc? (1972) and Paper Moon (1973). Set in a small, windswept Texas town of the 1950s, as its one movie theater closes, Last Picture Show is as touching a piece of Americana as The General, and one of the great examples of American New Wave. All three were bittersweet tributes to old Hollywood. All three made money and won Oscars: for Ben Johnson and Cloris Leachman in Picture Show, and for Tatum O’Neal in Paper Moon.

No one knows now exactly how Peter and Polly functioned — the 1984 film Irreconcilable Differences is based on their stormy marriage and divorce — but it was a partnership to treasure. Of course, he took most of the credit — that was his old arrogance. He became a media darling: boyishly handsome, witty, debonair, and cocksure. But his own trap was closing.

‘It was inevitable,’ he says. ‘My upbringing, the movies I’d seen, had made me totally vulnerable to falling in love with an actress. For Picture Show and the role of Jacie, we had found this girl from Memphis, Cybill Shepherd. She was 20 and perfect — very smart and funny. And I felt myself falling in love with her. I tried to avoid it. I told her, “I don’t know whether I want to go to bed with Jacie, or you.” Working that out was tough on Polly, and by the time of Paper Moon things had become very difficult. So I made Daisy Miller (1974) with Cybill, from Henry James. I think it’s a good picture, and she’s good in it. But there was such scandal, and a lot of people looking for revenge.’

They had some reason. Peter recognizes now that he had behaved badly, as if he thought he were a combination of Noël Coward and Cary Grant. He felt bound to tell the world that he knew everything. Billy Wilder had once said that Hollywood wasn’t so bad a place, for a nest of vipers: ‘Every now and then, it comes together — like everyone wanting to see Peter Bogdanovich get his comeuppance.’

A comeuppance of sorts came when Bogdanovich turned down the offer to direct not just Chinatown, but also The Godfather and The Exorcist. Worse was to come, however. In 1981, for a comedy called They All Laughed, he had discovered Dorothy Stratten, a lovely Playboy model and, as he believed, a great comedienne in the making. They tumbled into a love affair. But audiences didn’t laugh at the picture, and by then Dorothy had been murdered by a crazed ex-husband. This gruesome story was turned into another movie, Star 80, directed by Bob Fosse, with Mariel Hemingway as Dorothy and Roger Rees as a forlorn version of Peter. By 1985, Bogdanovich was forced into bankruptcy. He had always been extravagant and generous beyond his means.

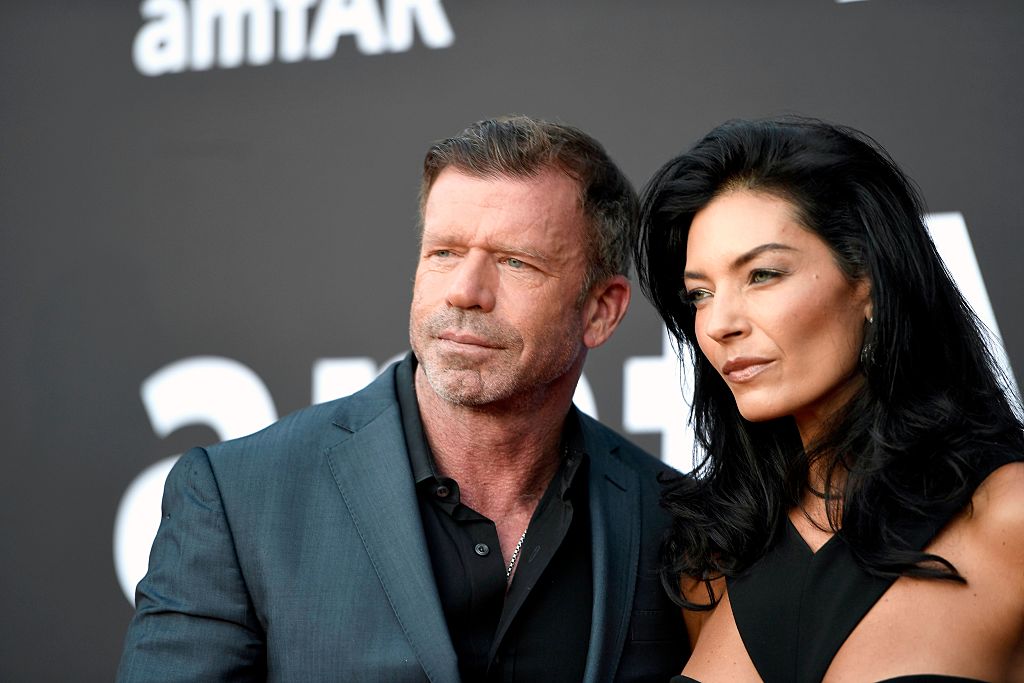

The Billy Wilder rebuke took it for granted that Bogdanovich’s brief rise had ended. But the truth is more complicated, and more valiant. He has carried on, much as Buster Keaton strung together the last decades of his life. Bogdanovich has made more films, without a trace of a hit. There was a second bankruptcy. He published anecdotal memoirs about the directors and actors he had known. In addition, in 1988, he had married Dorothy’s kid sister, Louise, who was nearly 30 years his junior. They are divorced now, yet still together. Louise is a collaborator on The Great Buster. Peter chuckles to recall the classic comedies of remarriage — like The Awful Truth or His Girl Friday — where a bond deepens after the parties are divorced.

He writes all the time, books and scripts — he has a comedy ready, created with Louise, which only waits on the approval of a big star who cannot quite yet be named. He has taught at the University of North Carolina School of the Arts; he acts in bit parts. ‘And Turner Classic Movies are going to do a season of my films. I’m going down to Atlanta tomorrow to shoot the introductions with Ben Mankiewicz. I think that’ll be nice.’ He sounds young again.

He has nearly finished an autobiography covering the years from 1964 to 1972. If he can be tough on himself and gentle to others — he has both urges in him — that could be an important book. He does not stop.

[special_offer]

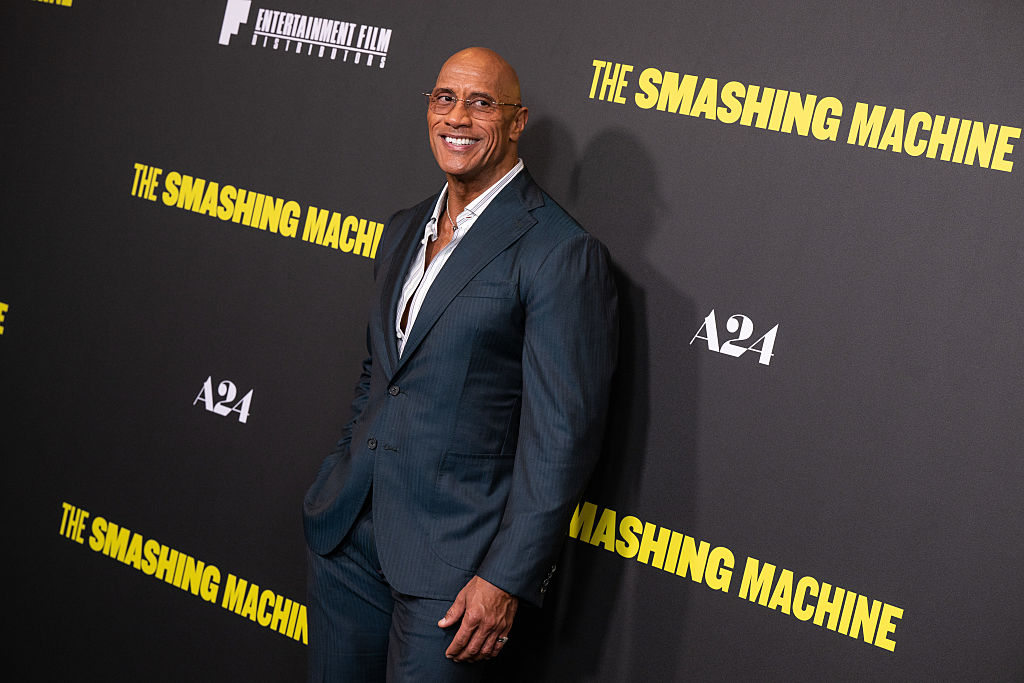

I ask him about The Other Side of the Wind, the movie left unfinished at the death of Orson Welles in 1985 but finally released last year. Peter had a key role in the film. Orson and he were like master and disciple, or father and son. In his affluent years in Beverly Hills, Bogdanovich supported and hosted Welles. He sighs over The Other Side of the Wind: it is not a satisfactory work, even if it needed to be shown. ‘It’s a decent version of what Orson intended, I suppose. But I’m not sure that it works, or whether Orson had shot the film he imagined.’ There had been talk once that Bogdanovich would finish the untidy picture, but legal and financial issues got in the way. The film stars Bogdanovich as a protégé of an aging Hollywood director. In this character you glimpse how much Bogdanovich loved Welles. Welles was Lear and Falstaff for a generation, and no one knew him better than Peter.

‘We did a scene together for the picture,’ he recalls. ‘It was between me and the director character, played by John Huston. But John couldn’t be there that day. So Orson sat in and read his lines, without being on camera. “Of course,” he told me, “this scene is really about you and me. You know that?”’ The affection is there on the screen. The whole fraught project speaks to the lifelong thwarted passion of Peter Bogdanovich. It’s reminiscent of the way Buster Keaton could make poetry and serenity out of disaster.

You can try writing Bogdanovich off. But take a look at The Great Buster, with Peter’s dry voice doing the narration, and revel in Keaton’s grace when a house and the world are ready to fall in on him. ‘I had never thought of making this film,’ says Bogdanovich. ‘But then I was approached and I looked at the pictures again. I thought, “My God, this is a genius.”’ The result is a movie to set beside What’s Up, Doc?. For they both offer the same sublime disdain for fates worse than death. One day, I guess, someone will make a picture about Bogdanovich that bears out the verdict of Martin Scorsese: ‘No one makes old movies better than Bogdanovich.’

The Other Side of the Wind is available on Netflix.