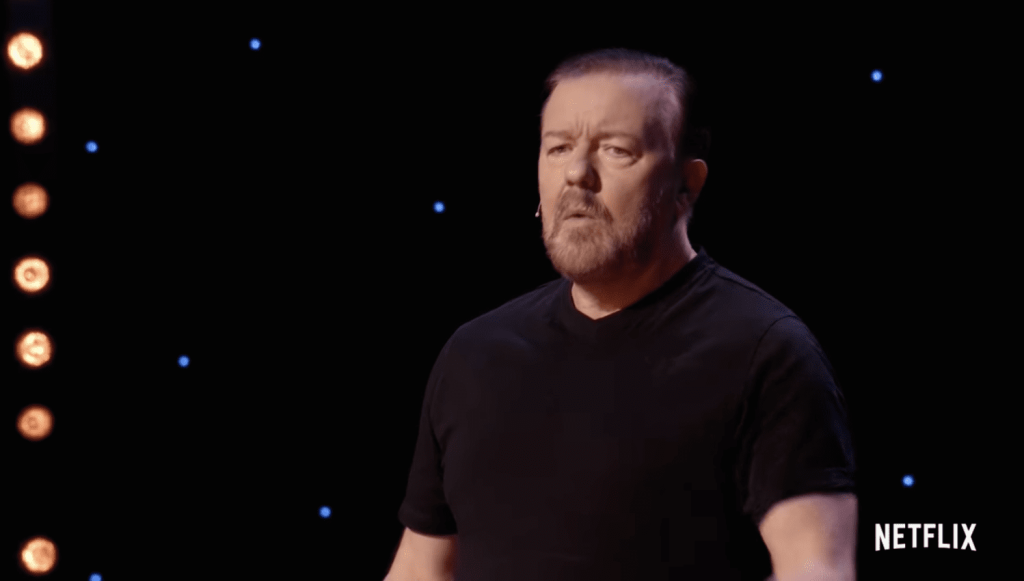

Ricky Gervais knew what he was doing and why he was doing it when he took on transgender activism in his new Netflix special, SuperNature. Three quarters of an hour into his set, he told his audience:

I talk about AIDS, famine, cancer, the Holocaust, rape, pedophilia… the one thing you should never joke about is the trans issue. They just want to be treated equally. I agree; that’s why I include them. But they know I’m joking about all the other stuff, but — they go — “no, he must mean that.”

The backlash to Gervais’s jokes suggest he was right. For all the subjects Gervais made gags about, it was his description of the “new women” as he called them, “the ones with beards,” that has caused outrage.

Gervais’s show was a full-fronted assault on the mantra that trans women are women. Was this wise? It was certainly unkind, but since when did comedy need to be kind? Last year, Dave Chappelle got into hot water when he set his sights on transgender ideology in his own Netflix special, The Closer. Chappelle explored the concept of punching up and punching down, something Gervais picked up on himself.

When we punch up we can be unkind with impunity. Political leaders, the wealthy, the privileged, royalty; when they are the butt of jokes, they are expected to take it. But punching down is different. Nowadays it takes a brave comedian to turn the heavy ammunition on the downtrodden and the marginalized. But Gervais went there when he quipped: “Will I ever find Schindler’s List funny ever again?”

If he could get away with joking about the Holocaust — surely the epitome of punching down — why did his jokes about trans people spark such outrage? Gervais’s explanation, which he offered to The Spectator on Tuesday night, perhaps reveals the answer:

My target wasn’t trans folk, but trans activist ideology. I’ve always confronted dogma that oppresses people and limits freedom of expression.

He is right to call this out. Whatever name we give it, trans activist ideology has shaken the foundations of our society, challenging the meaning of such fundamental concepts as men and women. When it becomes a courageous act to say that trans women are not women, we are being oppressed and our freedoms limited.

Gervais didn’t actually say that trans women are not women, though. He did not need to be so blunt because his comedy prized open the deception. Transgender ideology might have entranced political leaders, who seem unable to give straight answers to the most basic of questions. But this is no joking matter.

In Scotland, draft legislation could allow anyone over sixteen to change their legal sex without parental permission. Meanwhile children throughout the UK are being told that sex was arbitrarily assigned at birth, and feelings trump biology when it comes to distinguishing boys from girls. It is nonsense, but it is also dangerous. And all the time, too many people who should have said something have avoided the issue.

Gervais might be privileged — he joked about that as well in his set — but he uses his position to speak truth to power. Trans activist ideology has run unchecked for too long, and it is time to call it to account. As Gervais told The Spectator:

It was probably the most current, most talked about, taboo subject of the last couple of years. I deal in taboo subjects and have to confront the elephant in the room.

Well said.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.