Anyone under fifty may be unaware of how largely invisible gay Americans were until at least the 1980s. James Kirchick’s incredibly rich and impressively thorough Secret City does not mention Bowers v. Hardwick, the notorious 1986 Supreme Court ruling that upheld the criminalization of gay sexuality, but only post-Bowers did the push for gay equality, and eventually same-sex marriage, rapidly become what he rightly calls “the most successful social movement in American history.” In 1992, a Gallup poll indicated that 43 percent of Americans said they knew a gay person — double the figure from just seven years earlier — and across all of America it was that growing knowledge of the presence of gay people that allowed such a dramatic political transformation to take place.

But sexual complexity had long been “hiding in plain sight.” As far back as 1948, the famous Kinsey report detailed how no less than 37 percent of American men had had at least one homosexual experience. In the ensuing four decades, as “an evolving ethic of sexual freedom” took root, that percentage undoubtedly increased. Similarly, gay studies emerged as a top-quality field of scholarly endeavor. Historians such as the late John Boswell, George Chauncey, John D’Emilio and Martin Duberman fundamentally altered our understanding of the past and established, as Kirchick writes, that “homosexuality — both for the bonds it created and the fear it engendered — was a major historical phenomenon worthy of serious intellectual inquiry.”

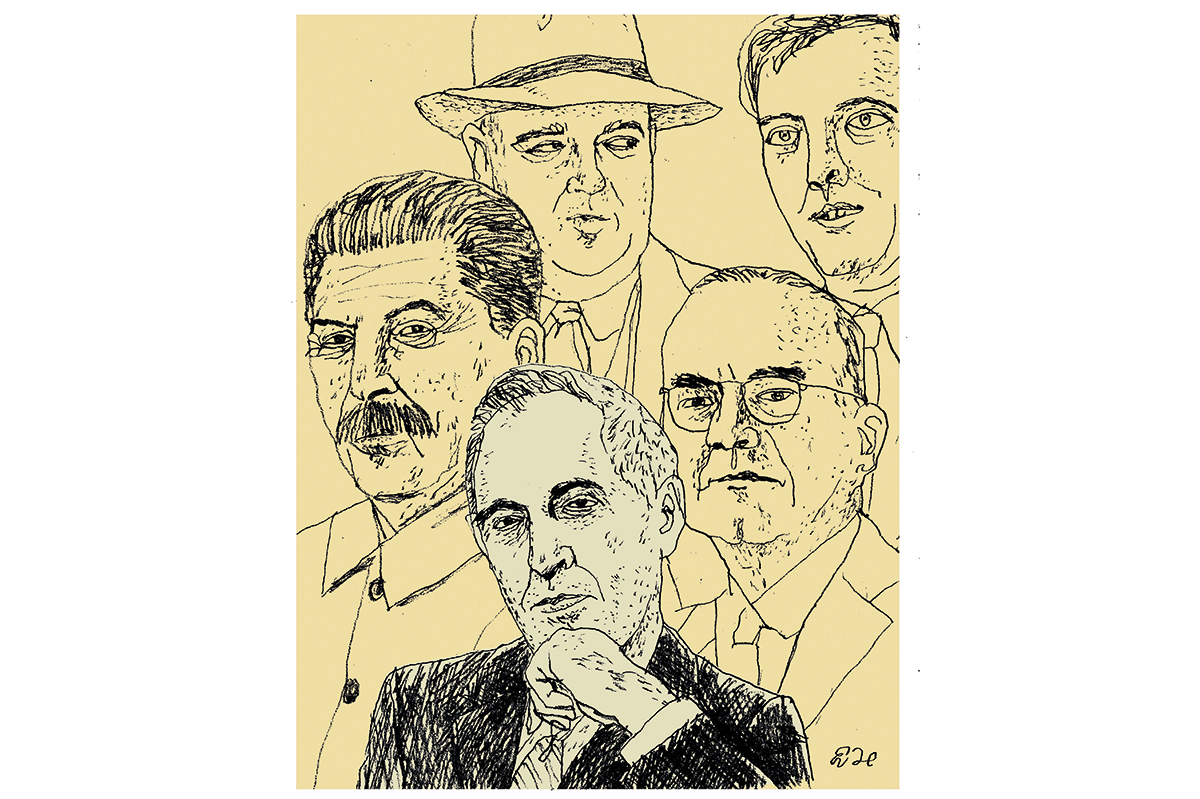

Kirchick understandably confesses how viewing “‘gay history’ as a subject separate and distinct from American history” is “erroneous and constrictive.” In Secret City he addresses “the wide-ranging influence of homosexuals on the nation’s capital” from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency through that of Bill Clinton. Again and again, DC’s “hidden history” reveals how “Washington was simultaneously the gayest and most anti-gay city in America,” with homophobic crusaders such as FBI director J. Edgar Hoover (himself the subject of countless unprovable rumors) doing battle against a cast of gay presidential counselors and Capitol Hill denizens whose cumulative numbers will surprise even experienced political historians.

Journalistic convention played a decisive role in the survival, and gradual expansion, of gay Washington. “Exposing homosexuals… was something that just wasn’t done in 1941,” when Roosevelt’s undersecretary of state, Sumner Welles, caused a major scandal by drunkenly propositioning black attendants on the president’s own special train. A year later, however, saw “the first ‘outing’ in American politics” when a liberal New York newspaper, abetted by American Civil Liberties Union doyen Morris Ernst, outed isolationist Massachusetts senator David Walsh as a patron of a gay bordello. Kirchick emphasizes that “it was Ernst and his liberal allies who used the accusation of homosexuality to destroy Walsh.” Come the mid-1950s, the ACLU remained expressly disinterested in gay freedom, proclaiming that it is “not within the province of the Union to evaluate the social validity of laws aimed at the suppression or elimination [!!!] of homosexuals.”

The 1950s witnessed a severe uptick in official homophobia as Executive Order 10450, signed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953, authorized the firing of any federal government employee against whom there was an allegation of “sexual perversion.” What historians call the “Lavender Scare” claimed close to ten thousand victims, yet most perverse of all was how a homosexual man — Eisenhower’s deeply closeted national security advisor, Robert Cutler — “helped codify the most far-reaching and destructive act of federal government discrimination against gay people in American history.”

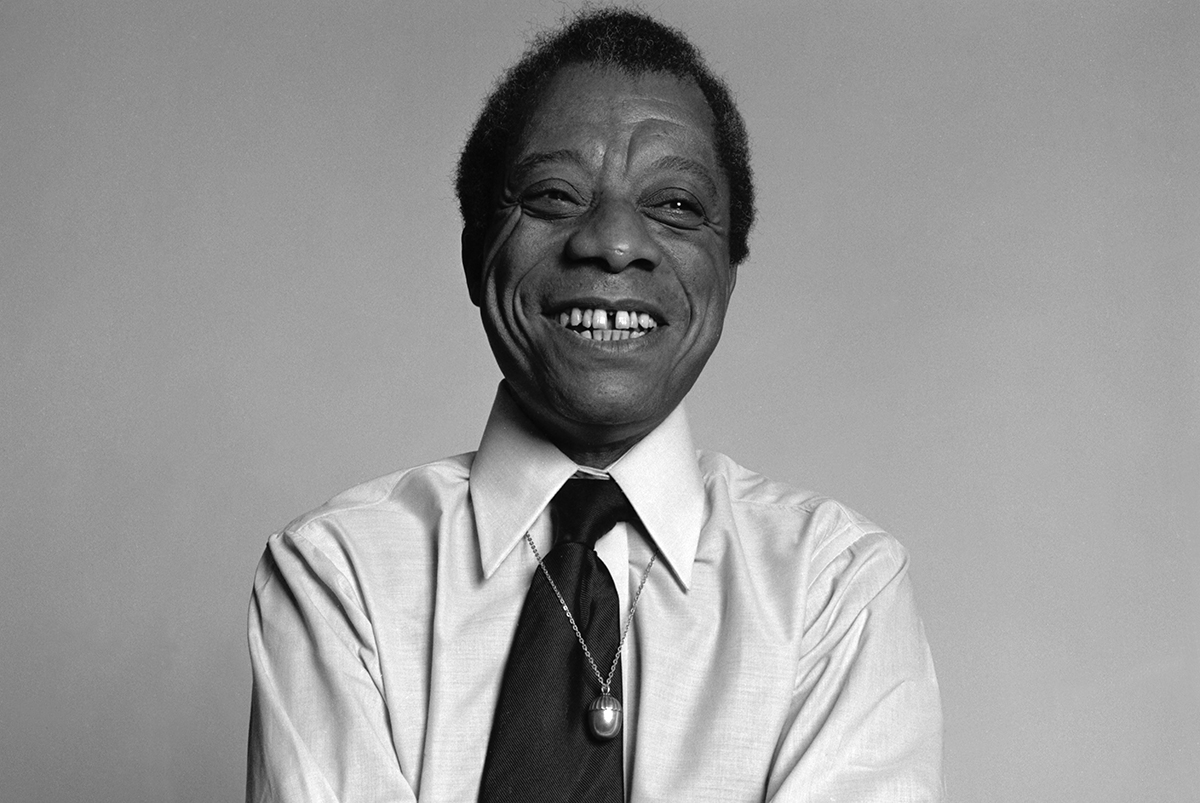

Amid “the secrecy that shrouded the Lavender Scare’s victims,” Frank Kameny, an astronomer with a Harvard PhD whom the Army Map Service fired in late 1957, “did what no man or woman in his position had yet done: he fought back.” A fellow gay activist later called Kameny “the most self-confident person whom I have ever known.” In stepping forward as “the first citizen to challenge the federal government over its discrimination against homosexuals,” Kameny “changed the course of history” and “lit a path for millions of men and women” who in future years would follow him out of the closet and into often courageous lives of activism.

If historical memory were a meritocracy, Frank Kameny’s name would be as well-known as that of Rosa Parks or Cesar Chavez. Yet Kirchick fails to highlight, and indeed omits from his lengthy bibliography, Eric Cervini’s superb 2020 biography of Kameny, The Deviant’s War.

Kameny’s struggle against federal personnel authorities continued into the 1960s, which also ushered in “the first presidential couple to socialize openly with gays.” Like his wife Jacqueline, John Kennedy “was remarkably relaxed among gay men,” perhaps in large part because his closest male friend since his school days, Lem Billings, had told Kennedy he was gay when they were still teenagers. JFK even gave Billings his own room at the White House, and Kirchick thoughtfully muses as to whether Kennedy’s own “compulsive” sexuality explains his serene rapport with Billings. “More than any president before and arguably since, Kennedy understood what it was to lead a secret life, the details of which would have shocked the average American, and this experience may have predisposed him to sympathize with other men who led sexually unorthodox lives.”

The Kennedy years also witnessed the largest civil rights demonstration in American history, the 1963 March on Washington. Its principal organizer, Bayard Rustin, became “the most prominent homosexual in America” when segregationist critics sought to cancel him because he was forthrightly gay. Yet civil rights leaders unanimously embraced Rustin, and in so doing established a pioneering precedent, for “up to this point, no gay person in American public life had survived a charge of homosexuality.”

But not everyone was as fortunate as Rustin, as President Lyndon B. Johnson’s top aide, Walter Jenkins, learned after being arrested for drunkenly performing oral sex on a random stranger within a block of the White House just four weeks before the 1964 presidential election. Johnson was mortified, and news of Jenkins’s arrest spread nationwide. Johnson tape-recorded most of his own telephone calls, and a week later he groused to one friend that “I’ve had a few drinks in my life and I want to call up my girlfriend,” a less-than-remarkable presidential confession. Yet Johnson remained in denial about Jenkins’s bisexuality, as his personal secretary, Mildred Stegall, explained years later. “Neither of us was willing to face up to the fact that he might have been guilty as charged.”

Washington’s lower-visibility population of gay women were of course at less risk, but if men could avoid the depredations of law enforcement, they could quietly lead their lives, too. In 1976 Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee explained that “public persons’ private lives tend to be their own business unless their personal conduct is alleged to violate the law or interfere with performance of the public job.”

Five years later, when Ronald and Nancy Reagan moved into the White House and inaugurated what Kirchick calls “the gayest of any presidential administration yet,” it already was an open secret that gay men were playing “a disproportionate role in the early American conservative movement.” Both President Reagan and his powerful counselor and attorney general, Ed Meese, were “practically surrounded by gay men,” and Nancy Reagan’s interior decorator, Ted Graber, “spent most of the first year of the administration living in the White House” as he oversaw renovations to the executive mansion. Indeed, Graber and his partner “became the first same-sex couple to stay overnight at the White House.”

Bradlee realized, as he wrote in a private memo, that there was “an important link between important parts of the conservative movement and homosexuals,” but the Post, like all other mainstream news outlets, remained committed to the public/private compartmentalization its editor had articulated a decade earlier. Kirchick’s decision to end his hugely valuable history in the late 1990s allows him to avoid confronting the revolution in professional values that has utterly transformed the behavior of American news media over the past quarter century, but Secret City is a work of enduring scholarship that will be read for decades to come.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2022 World edition.