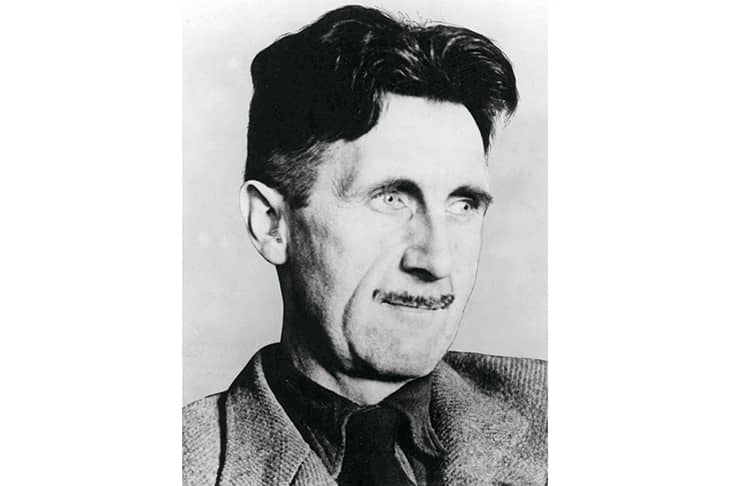

This is a book about George Orwell’s recognition that desire and joy can be forces of opposition to the authoritarian state and its intrusions. To explore the theme, Rebecca Solnit has produced a sequence of loosely linked essays around the roses and fruit bushes the author of Animal Farm planted in 1936 in the garden of his modest Hertfordshire house.

A Californian with more than twenty books behind her, Solnit opens this latest with a pilgrimage to Wallington, where Orwell’s Albertine roses have endured. The blooms instigate a reconsideration of the man “most famous for his prescient scrutiny of totalitarianism,” which in turn invites the author “to dig deeper” and question “who he was and who we were and where pleasure and beauty… fit into the life… of anyone who also cared about justice and truth.”

Solnit proceeds to consider roses culturally and historically, for example in their use in medieval recipes; the history and function of gardens; the role of class and race, and much more. She also sets the Hertfordshire planting in the context of the thirty-two-year-old Orwell’s life: he had just been north to research The Road to Wigan Pier, and was about to head to Spain to support the Republicans — “two journeys that would awaken him politically.”

Wigan leads Solnit to a chapter on coal and “the lurid misery on which Britain’s puissance was built,” and on “decades of fossil-fuel-sponsored climate denial.” She describes a 1946 Tribune essay in which Orwell mentions the planting as “a triumph of meandering,” and this phrase aptly sums up Orwell’s Roses. The most enjoyable sections among many for me were on Tina Modotti and Jamaica Kincaid. The first was the Italian-born photographer whose voluptuous 1924 image of roses printed on paper saturated with palladium, sold, as a contact print, for $165,000 — at the time the highest ever paid for a photograph. The Antiguan Kincaid, a novelist and keen gardener, receives a sensitive and acute reading, though Solnit could have made her a little less angry. Kincaid can be such a tender writer. I’m thinking of the semi-autobiographical Annie John.

The organization of material is schematic rather than thematic. Cultural references include Dante, Vermeer, Octavia Butler and Stalin (“surely Orwell’s principal muse”) as well as less familiar names such as the Latina muralist Juana Alicia, “a legendary figure in the San Francisco Bay Area.” Voltaire jostles his way in, of course, with Candide retreating to his garden, “a decision that has often been framed as a withdrawal from the world and politics.” But is it? Is Candide “just recharging, preparatory to returning to the fray?”

Creative non-fiction is taught in the academy now and Solnit, among its finest practitioners, is explicit that the genre does not involve departure from the facts. It means thinking creatively about the facts and being creative about which ones you put together.

Despite first-person commentary, and a judiciously spare sprinkling of autobiography, Solnit is an agent of her material, not a character within it. If I were to pick one of her backlist most similar in temperament to Orwell’s Roses, it would be River of Shadow, a dazzling portrait of the British-born photographer Eadweard Muybridge. I can criticize only in these unforgettable pages a tendency towards the sweeping statement in the consideration of history overall. “Much of the left of the first half of the twentieth century,” Solnit breezes, “was akin to someone who has fallen in love, and whose beloved has become increasingly monstrous and controlling.” Sort of.

It turns out that Joshua Reynolds’s largest work, from the early 1760s, now in New York’s Met, depicts Orwell’s great-great-grandfather Charles Blair alongside Henry Fane, whose own father became the 8th Earl of Westmoreland. Blair’s money came from sugar, which meant from the backs of slaves. The horror of slavery leads to an investigation of the rose business, as Solnit flies to Bogotá and learns from a labor organizer about brutal working conditions in a complex that ships six million roses to the US for Valentine’s Day and another six million for Mother’s Day.

The author seeks to mitigate “a stern and gloomy portrait in shades of gray” that emerges from the biographies, finding “another Orwell,” who delighted in, and often wrote about, the natural world. (“Outside my work,” he said in 1940, “the thing I care most about is gardening, especially vegetable gardening.”) Noting the “totemic figure” he has become, “claimed by people across the political spectrum,” Solnit calls the new version “this unfamiliar Orwell.” Several times she expresses the belief that the “crucial beauty” for which Orwell strove is that in which ethics and aesthetics are inseparable. Golly, I wonder.

The volume ends with Orwell on Jura, and a close look at Nineteen Eighty-Four, Solnit challenges Margaret Atwood’s contention that the novel is not quite the dystopia it is often taken for. In the end I agreed with both of them. The pages here on Orwell’s last days are wonderful and moving. He believed that pleasures such as gardening can be a force of opposition. As Solnit concludes her fine and thoughtful book: “The work he did is everyone’s job now.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.